A recession is what results when an economy stops growing. The National Bureau of Economic Research, the group entrusted to call the beginning and end dates of a recession, defines it as “a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.”

Economists define a recession as two consecutive quarters of decline in GDP, which is the total value of all goods and services a country produces.

We aren’t there yet, but the war between Russia and Ukraine has prompted a re-evaluation of the growth prospects for the world economy and some of the major players in it. According to CBC News, the International Monetary Fund is blaming the war for disrupting global commerce, pushing up oil prices, threatening food supplies and increasing uncertainty already heightened by the coronavirus.

The 190-country lender therefore slashed its global growth forecast to 3.6% this year and next.

The picture looks quite different from January, when the IMF was predicting 4.4% global growth in 2022, and 3.8% in 2023, following a blistering 6% in 2021, the latter due to most countries posting strong recoveries from the pandemic that hit them in 2020.

Europe is expected to bear the brunt of the economic fallout from the war, given how dependent it is on Russian energy. For the 19 countries that share the euro, the IMF expects just 2.8% growth in 2022, down sharply from the 3.8% it expected in January and 5.3% last year.

The Chinese economy’s growth rate has been nearly cut in half, from 8.1% in 2021 to an expected 4.4% this year.

The IMF forecasts growth in the world’s largest economy, the United States, to fall to 3.7% this year, down from 4% previously, and significantly slower than last year’s 5.7%, which was the best year for the US economy since 1984.

The IMF’s dismal growth forecasts coincide with a higher frequency of chatter among financial news sites of the dreaded R word: recession.

The chatter picked up around Easter Sunday when Goldman Sachs published a report putting the odds of a recession at about 35% over the next two years. The influential investment bank noted that 11 out of 14 tightening cycles in the US since World War II have been followed by a recession within two years.

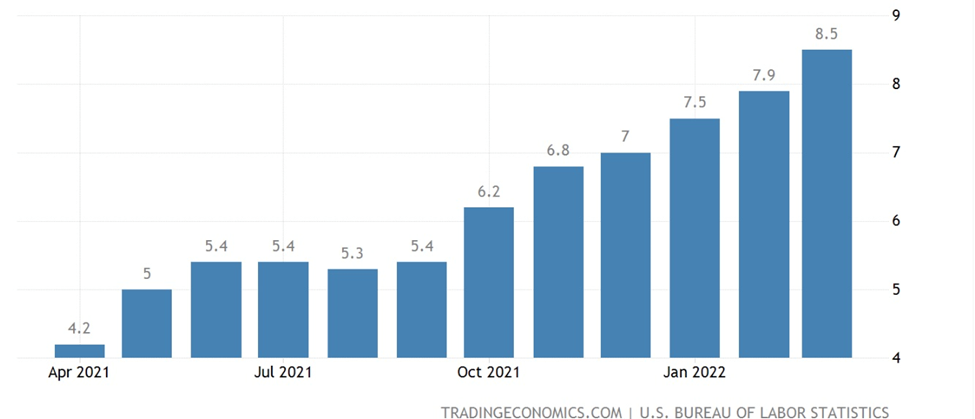

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you are aware that the US Federal Reserve has telegraphed a series of interest rate hikes this year to combat 40-year-high inflation, which registered at 8.5% in March.

US inflation. Source: Trading Economics

US inflation. Source: Trading Economics

Bloomberg writes, Wall Street’s focus seems to have changed in recent days from how fast and how high the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates to the timing of the next recession. The two are not mutually exclusive. The consensus is that the Fed is so far behind that curve when it comes to increasing rates that it will have no choice but to tighten monetary policy so severely that it forces the economy to contract to get inflation under control.

At AOTH, we’ve maintained this view for months, however our thinking has changed, having seen new numbers, particularly with respect to the health of the American consumer. More on that below.

First, a bit of background.

In March the Fed raised interest rates by 0.25%, the first increase since December 2018, to address the highest inflation since 1982. Clearly it won’t be enough and the central bank will be pressured to add more rate hikes. Officials are targeting rate rises at each of the remaining six Fed meetings in 2022. That would bring the federal funds rate to 1.75% by the end of the year, if the six additional increases are @ 0.25%, or 3.25% or they raise by 50 basis points each meeting (+0.5%).

There is a line of thinking, and we agreed, that the Powell Fed’s intention is to “go hostile”, that the only way it is able to fight the level of inflation that has permeated the economy, is to “crash the markets”. That is precisely what Paul Volcker’s Fed did in the early 1980s.

History tells us that previous Fed rate hikes to deal with uncomfortably high inflation resulted in recessions.

During the 1970s consumer price inflation averaged 7%. To tackle it, then-Fed chair Paul Volcker dramatically raised interest rates. From 11.2% in 1979, Volcker and his board of governors through a series of rate hikes increased the federal funds to 20% in June 1981. This led to a rise in the prime rate to 21.5%, which was the tipping point for the recession to follow, lasting two years.

The difference between 1979 inflation and 2022’s is the humongous debt pile preventing the Fed from raising rates beyond nominal. Goldman Sachs says the main goal of the Fed’s planned rate hikes is to slow wage growth from 5-6% to 4-5%, helping cool inflation close to the Fed’s 2% target in 2023-24.

Remember, the Fed is constrained in how much further it can lift rates, due to the crushing amount of debt — including government, corporate and household. The national debt currently sits at $30 trillion, with interest payments amounting to nearly $600 billion. Each interest rate rise means the federal government must spend more on interest. Higher debt servicing costs take away from other spending that that will have to be cut, as the government tries to keep its annual budget deficit under control. Whether the budget cuts are to health, education, transportation or veterans’ benefits, you or someone you know could be affected.

Let’s also remember what happened when the Fed tried to raise interest rates in 2018. They only got to 2% when the stock market started to tank, prompting them to reverse course, and re-instate low interest rates.

The question this time, is how aggressive will the Fed be in raising interest rates to fight inflation?

Recessionistas

Some commentators believe the Fed will go so far as to crash the markets and cause a recession to crush demand.

Even though employers have added nearly 6.5 million jobs in the last 12 months and unemployment has fallen to just 3.6%, economist Matthew Luzzetti believes that the sizzling labor market is helping to push inflation higher than the Fed’s 2% target.

Luzzetti is quoted by NPR saying that the Fed therefore has no choice but to crack down hard, with significantly higher interest rates. He predicts these aggressive rate hikes will push the economy into a mild recession by late next year.

Luzzetti is certainly not alone in this view. As NPR states, Economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal put the odds of recession in the next 12 months at 28%, up from 13% a year ago.

Larry Summers, the former Treasury Secretary, said the chance of the Fed hitting the nominal rate — high enough to cool aggregate demand, but not so high as to kill consumer spending (and borrowing), which makes up 70% of the economy — aren’t great.

“It could happen. But I don’t think it’s terribly likely,” NPR quotes him saying.

The economic team at Goldman Sachs believes the US economy will suffer a “hard landing” in the next two years, putting the odds of recession at about 15% in the next 12 months and 35% over the next 24 months.

According to Marketwatch, New York Fed President John said achieving a soft landing would not be easy, while his precedessor at the New York Fed, William Dudley, said a hard landing was inevitable.

In an article titled “Is A Bear Market Lurking”, author Lance Roberts references the stock market to explain why the Fed nearly always “breaks the market” when raising interest rates.

Consider: stock valuations in 1929, 2000 and 2008 were abnormally high, just prior to each recession. Think of the crash as a blunt instrument that pounds valuations back into line. “Historically, the Federal Reserve hikes rates until ‘something breaks,’ which resolves the overvaluation problem (i.e., prices fall sharply),” Roberts writes.

It’s easy to see how this leads into a recession. Corporate earnings remain elevated heading into a tightening campaign, but higher interest rates and surging input costs (inflation) put earnings at risk.

“The whole point of the Fed hiking rates is to slow economic growth, thereby reducing inflation. Unfortunately, with the economy already slowing, additional tightening could exacerbate the risk of an economic contraction, given the dependence on low rates to support economic growth. Given that earnings are highly correlated to economic growth, earnings don’t survive rate hikes.”

Roberts notes that companies will absorb the input costs they can’t pass onto consumers, but eventually, doing so will impair profitability.

Inflation + higher interest rates + lower earnings = a stock market crash that either accompanies, or causes a recession.

The power of the consumer

Apart from the amount of debt, the other thing that differentiates the current Fed tightening cycle from previous ones is the robust financial situation the US household finds itself in.

The coronavirus pandemic was unusual for a number of reasons, not least of which was the trillions of dollars worth of government spending that was pumped into the economy for pandemic relief. Direct stimulus payments and other generous social programs lifted checkable deposits for households from $1.16 trillion at the end of 2019 to $4.06T in December 2021. That is a massive cash cushion consumers are sitting on — nearly quadruple the previous high of $1.41T.

A Washington Post article reported that Americans currently have an extra $2.6 trillion in savings. High earners are holding an average $1,300 more in their bank accounts than before the pandemic, while low-income households retain substantial savings from their stimulus and unemployment checks, data shows.

Bloomberg notes that even though most pandemic relief programs have ended, US tax refunds are surging, having risen to an average $3,175 this year, up nearly 10% form the same period in 2021.

Americans therefore have lots of cash and surprisingly low levels of debt (considering near zero interest rates), meaning that more spending is likely, even with a slowdown in the economy. Remember the key to a country’s economic health is the consumer. Their spending makes up 70% of the US’s, and the global economy.

Inflation: mostly (lack of) supply-driven

The Fed thinks that raising interest rates will quell demand for goods and services (aggregate/ total demand) which is exceeding aggregate supply, causing inflation. Lessen the demand, lower the inflation. Simple, right?

Wrong. I have no problem agreeing that demand is partially responsible for decades-high inflation in the US, Canada and Europe. But attributing higher prices to the fact that the economic rebound has outpaced the ability of manufacturers to brings goods like semi-conductors to market (the “supply chain issues” theory that has been repeated ad nauseum — singer Jack White even named his tour after it) — but it’s not the main reason.

Also, our current bout of inflation is unlike the last time prices rose beyond the Fed’s 2% target (from about -1.5% in August 2009 to 3.75% in August 2011), which was all about quantitative easing.

The real culprit is not supply chains but actual supply, especially of raw-material commodities that have skyrocketed in recent months. A deeper understanding reveals that the supply shortages we are currently experiencing are not temporary, but structural in nature.

A few examples will make the point.

Energy

Before the war in Ukraine, in 2021, the natural gas market had slipped into severe deficit, hiking prices.

The price rise was not only due to 2020’s depleted inventories and a cold autumn, but a faster than expected recovery from the pandemic, ultra-low interest rates and record government spending on pandemic relief that boosted spending and increased demand for energy.

By September 2021, NG prices in Europe and Asia reached $32-33 per mmbtu, equivalent to a crude price of $200 per barrel. Electricity prices across Europe set fresh and frightening highs, including in Germany, where it jumped to 431 euros per megawatt-hour.

The war in Ukraine has boosted European natural gas prices even higher, hitting a record on March 7. As the EU considers a full ban on Russian energy exports, German businesses and unions are saying “nein”. They prefer a gradual phase-out of Russian oil by year-end and of Russian gas within two years.

“A rapid gas embargo would lead to loss of production, shutdowns, a further de-industrialization and the long-term loss of work positions in Germany,” AP quoted the chairmen of the BDA employer’s group and the DGB trade union confederation as saying Monday.

Germany depends on Russia for about a third of its energy consumption. Italy, Austria and Hungary are also fearful of an immediate ban.

European natural gas prices. Source: Trading Economics

European natural gas prices. Source: Trading Economics

In the UK, skyrocketing utility bills are eroding living standards and pushing a growing number of customers into “fuel poverty”. According to the Resolution Foundation, via Zero Hedge, the average family will pay 1,100 more British pounds (USD$1,435) over the next 12 months just to satisfy their energy needs.

7% inflation has pushed the UK Misery Index, an economic indicator to gauge how the average person is doing, to three-decade highs.

The United States hasn’t been hit as hard as Europe regarding natural gas prices, however US natural gas reportedly surged to a 13-year high, Monday, “as robust demand tests drillers’ ability to expand supplies.”

According to Bloomberg, Backup inventories held in underground caverns and aquifers are below normal for this time of year and the U.S. is exporting every molecule of liquefied natural gas possible to help Europe reduce its reliance on Russian energy supplies. At the same time, production remains below pre-pandemic levels, despite government forecasts calling for record production from the Permian basin this Spring…

A shortage of coal in the U.S. has also helped fuel the gas rally, limiting power generators’ ability to switch fuels.

At AOTH, we don’t see energy inflation stopping. Trouble is, we’ve been so focused on expanding renewable energy, before it can actually replace fossil fuels, that we have virtually guaranteed oil (and natural gas) prices will stay high for the foreseeable future. Read more

Food

The war in Ukraine is accelerating a global food crisis that is reverberating across the world, in countries that literally depend on Russia and Ukraine for putting food on the table. (together they account for 25% of global wheat shipments)

Climate change is making it more difficult to irrigate fields and pastures. Droughts and floods are ruining crops or reducing yields, forcing some farmers into bankruptcy. Many grocery items have exploded in price due to covid-related supply disruptions, bad weather, the Russo-Ukrainian war, or a combination of the three.

Grain stockpiles are poised to decline for a fifth straight year, due to a combination of higher shipping costs, energy inflation, extreme weather and labor shortages. If the world were to become short of grains, people would starve; wheat, corn and rice account for over 40% of all calories consumed.

Even before the conflict began, food prices were at record highs, the benchmark UN index increasing more than 40% over the past four years. Food insecurity has doubled in the past two years, and the World Food Program estimates 45 million people are on the brink of famine.

In fact global food prices have exceeded levels only seen during the Arab Spring, when riots erupted over a shortage of bread. In March the UN’s food price index jumped 12.6%, breaking a new record from the previous one set in February, and 33% higher than March of 2021.

Food inflation is a regular topic on news programs, and prices just keep increasing.

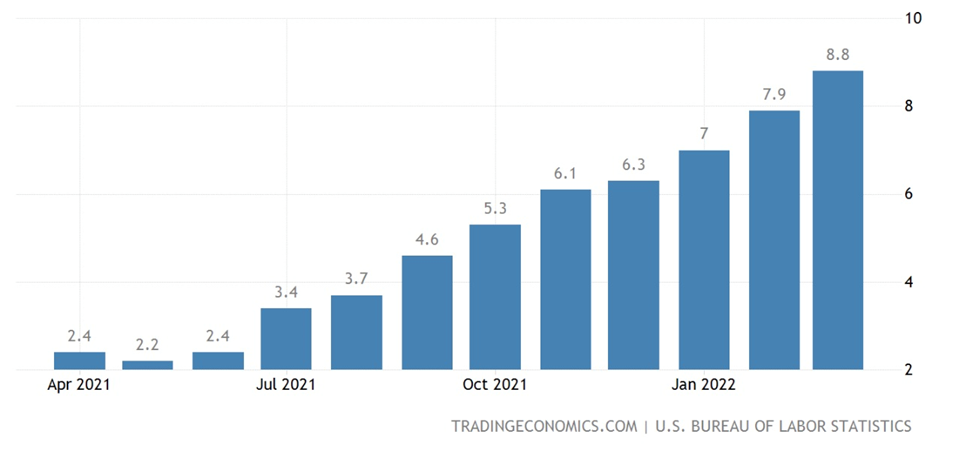

US food inflation. Source: Trading Economics

US food inflation. Source: Trading Economics

On Monday the price of corn futures hit $8 a bushel, the highest since 2008, as traders factored in dwindling supplies. A drought across the US Midwest is partly responsible, but so is the war in Ukraine. According to Zero Hedge, The global outlook for corn supplies has plunged since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine began in late February. The war-torn country supplies a fifth of the world’s corn and could experience a 50% decline in output this year.

The Biden administration’s recent decision to expand biofuel sales, to curb soaring gasoline prices, is exacerbating the problem. The ethanol industry competes with farmers for corn feedstock, making less available to the food industry and raising prices.

Fertilizer

Soaring fertilizer costs have forced some US farmers to plant soybeans instead of corn, as the former requires fewer nutrients.

Last year the fertilizer market was pummeled due to extreme weather, plant shutdowns and the rising cost of natural gas, the main feedstock for nitrogen fertilizer. The situation has worsened due to the war in Ukraine, with Russia being a major producer of nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus fertilizers. The country is the world’s largest exporter of urea and no. 2 for potash.

As punishment for opposing its actions in Ukraine, Russia is limiting fertilizer exports to “unfriendly countries”. This includes the United States, a major importer of Russian nitrogen and potash.

Elevated fertilizer prices are also taking their toll on rice farmers, many of whom must reduce the amount of nutrients to save costs, thereby threatening future harvests.

According to Bloomberg, via Zero Hedge, farmers in the largest rice-producing countries of China, India, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Vietnam could experience reduced output, with the International Rice Institute warning that harvests could plunge as much as 10% next season. That equates to about 36 million tons of rice, enough to feed a half billion people.

Metals

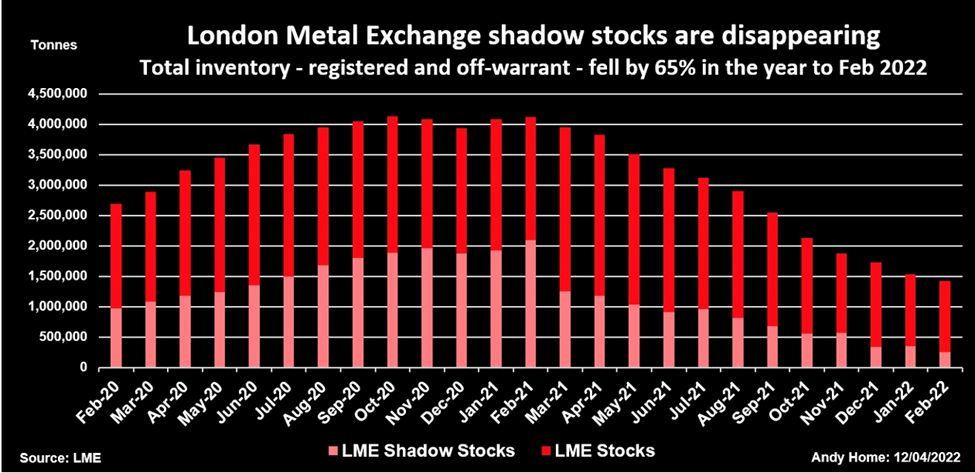

Bloomberg reported earlier this month that inventories across London Metal Exchange warehouses have “dropped to perilously low levels, raising the threat of further spikes in everything from aluminum to zinc.”

Available stockpiles across the six contracts on the LME were at their lowest levels since 1997. Goldman Sachs warned that copper is “sleepwalking towards a stockout” and zinc inventories fell more than 60% in under three weeks, as Trafigura Group purchased large volumes.

The sharp drop echoes a similar drawdown in copper last year, when stocks of the red metal plunged to the lowest since 1974.

The markets for other electrification and decarbonization metals look equally bullish.

The price of lithium is up more than 400%, as automakers race to secure supplies, expecting a surge in demand for the EV battery ingredient.

A string of annual supply deficits starting in 2018, combined with higher sales of gasoline vs diesel units, culminated in palladium’s historic price pinnacle of $2,830 per ounce in May, 2021.

The platinum-group metal has enjoyed a spectacular ride since Russia invaded Ukraine at the end of February. Year to date, spot palladium has climbed an impressive 30%.

The outlook for silver, used extensively in solar panels, among a wide range of industrial applications, is especially promising this year.

According to the Silver Institute, global demand for silver is expected to hit a record 1.112 billion ounces in 2022, driven by industrial fabrication, which is forecast to improve by 5%, “as silver’s use expands in both traditional and critical green technologies.”

After shifting to a deficit in 2021 for the first time in six years, SI says the silver market is expected to record a supply shortfall of 20 million ounces this year.

Many analysts see metals heading higher as shortages on the LME and the wider physical markets deepen.

Reuters said last week that inventories across London Metal Exchange warehouses of copper, lead, nickel, zinc and tin haven’t been this low for 20 years, with the total amount of registered metal in the LME’s global warehouse network falling below 1 million tonnes in March.

The result is higher prices and increased volatility.

There are mainly three reasons for the low volume of metal being warehoused: pandemic lockdowns, logistical disruptions and smelter cutbacks in Europe.

An even bigger draw-down is occurring within LME shadow inventories, referring to metal that is stored off-market but is under a warehousing contract allowing for exchange delivery.

These “off-warrant” stocks amounted to 256,000 tonnes at the end of February, down 88% on the 2Mt sitting in shadow inventories a year earlier. As shown in the chart below, total inventory, i.e., registered and off-warrant, fell by 65% in the year to February 2022.

Conclusion

Economic growth requires the supply of raw materials for manufacturing end-products, and a litany of other industrial activities, including home construction, replacing and building new infrastructure, developing a global electrified vehicle/ rail transportation system, and constructing lower-carbon sources of electricity generation.

Unless all of these areas are continuously supplied, economic growth will drop off, hurting employment and lowering our standard of living. This becomes a major challenge when demand is coming from so many directions at the same time. Read more

As we stated at the top, the IMF recently slashed its global growth forecast to 3.6% this year and next. If GDP growth falls for two consecutive quarters, we will officially be in a recession.

Inflation is chipping away at the standard of living in a number of developed countries. Here in North America, it’s the worst we’ve seen since the 1980s. Everything is going up, and people are hurting, especially the poor and working poor. For those with mortgages, loans and credit card debt, higher interest rates will only add to the misery.

Yet one of the Federal Reserve’s most important tools for fighting inflation is to raise rates. We asked the question, how aggressive will the Fed be in raising interest rates to deal with inflation?

Previously I believed that the Fed would “go hostile” in raising rates so high, it would crash the markets and cause a recession. Having seen the consumer savings figures, I’m no longer so sure.

Direct stimulus payments and other generous social programs lifted checkable deposits for households from $1.16 trillion at the end of 2019 to $4.06T in December. That is a massive cash cushion consumers are sitting on — nearly quadruple the previous high of $1.41T.

A Washington Post article reported that Americans currently have an extra $2.6 trillion in savings.

Raising interest rates is not going to stop consumers from spending, if that is the Fed’s goal.

The Fed thinks they’re going to create demand destruction through higher rates, and they may succeed, to a limited extent. However, as we have argued from the beginning, this inflation is not about quantitative easing, and reducing the Fed’s $8 trillion balance sheet — that won’t curb inflation.

Remember, the Fed is constrained in how much further it can lift rates, due to the crushing amount of debt — including government, corporate and household.

Instead, we believe the Fed will raise, but not to the point where it hurts the economy and causes a recession. A middling amount, say 2-3%, will likely be enough for the Fed to say it is “doing something” about inflation, even though no amount of interest rate hikes will do anything to fix the structural shortages in commodities we have discussed in this article. And how could it?

How does raising rates to curb demand avert the energy crisis or grow more food?

Arguably the most valuable aspect of raising rates is giving the Fed a tool that has been missing in their toolbox. With interest rates at or near zero, the Fed has no leverage, no wiggle room if it needs to cut rates in the event of a severe economic downturn. It’s already gone as low as it can go.

Even lifting rates to 2% will give the central bank what it needs to rebalance the economy, should it need to return to lowering rates.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.