Jeffrey Tucker is pointing out the view that is almost inescapable, at least, as one of two clear alternatives, regarding the Fed’s large crisis-scale rate cut at a time when it says the economy is “strong.” Adjusting the trim tabs on its 747 for a smooth and level landing is one thing, but gunning the engines is another—something only done if the plane is coming down much too quickly:

By dropping rates dramatically only a month and a half before an election, the Fed is playing with fire. The election, by all visuals, would seem to pit the establishment against an insurgent populist movement. Regardless of the countercyclical motives, it’s a move that has been widely seen as deeply political.

That is one scenario I pointed out, but Tucker also lays out the only other scenario that made sense to me:

The inflation fight of the last two years seems to have drawn down the rate of price increases, though the battle is far from over. But now the Fed believes it has another problem with which to deal, namely weakness in the labor market.

Recessionary conditions are everywhere except on official paper. Bankruptcies are quite high already. Inflation is underestimated and growth overestimated. At this point, everyone in the know is aware.

As I laid out in the editorial about consumer sentiment, consumers are aware things are not as good as they’re being told, and an increasing throng of consumers is starting to believe we are already in a recession. GDP is overstating growth, and according to Danielle DiMartino Booth, also in our editorial, we’re about to see GDP revised down by as much as we saw the Biden administration’s job statistics revised down this past summer—an error even the Fed commented on more than once.

The populace clearly feels the economy is lagging and inflation is about to start rising again, according to the reports. Tucker, too, sees inflation as something that will see a resurgence not far around the bend:

There is another factor of which many people are unaware. The money stock is already on the increase, either due to relaxed lending standards, more debt purchases by the Fed, or both. This has combined with an inevitable increase in money velocity … further fuels prices pressure.

The uptrend in money supply, he notes, has been a one-year trend, putting it about right with the Fed’s lag time for monetary policy of 1-1.5 years to show up in the final months of this year.

And then he throws in some fun:

There is nothing necessary about such an institution. To be sure, eliminating it would amount to a shock to the system of the most severe sort. Wall Street would scream. Central banks around the world would panic. Big media would denounce the move, and all establishment economists would be in freak-out mode. All that aside, there is no getting around two crucial facts: such an institution is enormously powerful but nowhere in the Constitution, and none of its grand promises have worked out.

That would be fun; but, if wishes were horses, beggars could ride, which would be most of us once the Fed is done with us.

In an ideal world, the Fed would be defanged of 90% of its power by complete removal of the jobs mandate and then notched down another five points by setting mandatory monetary policy at maintaining a symmetric (since the Fed likes that word only when it works for it but not when it works against its inflation goals) inflation level of 0%. Like a heat-seeking missile that symmetric approach would force the Fed to keep zeroing in on 0% by going negative for a while if it must in order to correct for months of straying positive. There would be no benefit in staying positive. The longer it let inflation flourish, the longer it would have to tighten money on the other side, giving lots of incentive to keep things as smooth as possible.

Besides helping with regulating its member banks, the Fed would have one mandate—truly stable money. It’s the labor mandate (which it originally did not have) that gives it all its economic manipulation powers … at which it has performed quite poorly.

The Fed strikes out with labor

The fact is the Fed keeps sending us back into the same holes, or maybe it is more accurate to say, that it digs up dirt to fill one hole, creating the very next hole we fall into. It’s an endless regression of cycles that wind up resulting in bigger and bigger holes because the economy becomes less and less responsive to the stimulus and debt the Fed supports in order to get us out of a hole. The Fed tries to solve holes by digging us out of them.

(All of which digresses back to my easy-to-read little book: DOWNTIME: Why We Fail to Recover from Rinse and Repeat Recession Cycles. We never learn.)

Proof that the Fed does poorly with the labor market can be seen in how all of the Fed’s financial stimulus has inured for decades to the benefit of the richest of stockholders, banksters, and corporate executives while almost no benefit has been experienced by labor. The Fed has known this all along and talked about it much in order to pretend it cares. If it really cared, it would stop taking and stop aiming all its policies at pumping money directly into the pockets of the richest economic rulers in the nation.

Other proof of how poorly the Fed does with labor can be seen in how deeply government jobs data got revised down from the positive results Bidenomics had been showing for the past year to, at best, very modest results. Then, when adjusted for how much massive government debt we added in order to achieve those modest results, the real results sink from “modest” to “abysmal.” We got nothing for the money so far.

You can say that is just Biden’s fault and not the Feds, except that the Fed originally made Bidenomics possible with dirt-cheap financing on the basis that it would be good for labor (and for inflation). Instead, it created inflation that ate away all the wage benefits that labor experienced!

We are now “reckoning with budding parallels to the Dotcom Bubble & Bust,” says economist Wolf Richter. The hot air is coming out of the balloon, and it is hitting the one area where jobs and wages saw the greatest growth.

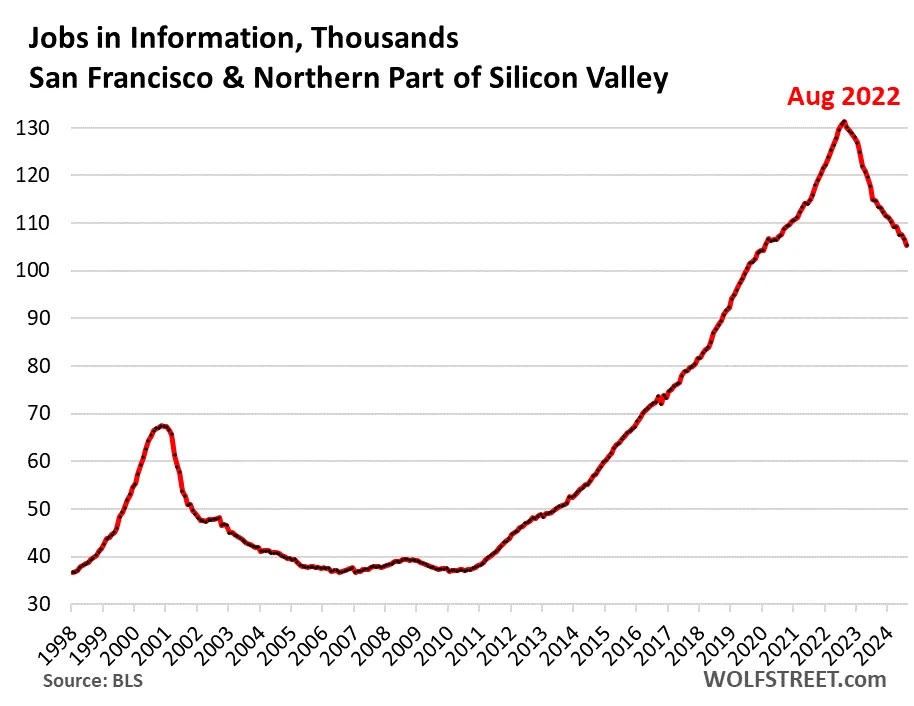

In San Francisco and the northern part of Silicon Valley, one of the epicenters of tech jobs in the US, has seen large scale declines of jobs in tech, social-media, and finance since the end of the pandemic hiring boom in mid-2022 despite the AI-related hiring boom.

And August made it a lot worse with large month-to-month drops of jobs in Information (-1.2%) and in Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services (-1.1%), according to the Establishment Survey by the Bureau of Labor Statistics for the metropolitan division “San Francisco-Redwood City-South San Francisco,” which spans San Francisco County and San Mateo County. The data was released on Friday.

And that is the very area that Bidenomics’ “Build Back Better” program was supposed to help. We’re supposedly building lots of new tech factories to strengthen the labor market.

That looks like this:

A lot of that is the reversal of crazy hiring that happened in tech during the explosion of virtual work environments under foolish Covid lockdowns, which is now unwinding.

I’ve argued for a number of years, that this recession was going to look a lot like the dot-com bust, and we are well down that path already.

This is also having a major impact on major banks already:

Wells Fargo is still headquartered in San Francisco, but it has many employment centers around the US, and has been building a major campus in Texas to open in 2025. Rumors have been flying for years that it would move its headquarters out of San Francisco. In October 2022, the San Francisco Business Times reported that no one from the bank’s 17-member “senior leadership team” was still based at the headquarters in San Francisco. Employment at its headquarters has been shrinking for years. In June 2023, Wells Fargo sold a 13-story office tower near its headquarters building at 60% below its 2005 purchase price.

And you may easily remember this part of this regional banking bust:

Then, in the spring of 2023, two regional banks failed that the tech and startup scene had relied on – Silicon Valley Bank, headquartered in Santa Clara (not part of this metro), and First Republic, headquartered in San Francisco.

So, high-tech is taking the worst part of declining labor conditions right now, perfectly in line with what one would expect in another dot-com bust of the kind the experts were saying early this summer was impossible because AI was leading tech upward in an inexorable march to a glorious future and could, therefore, never see a crash like we saw in the 2000 dot-com bust. Same nonsense that was pitched before the dot-com bust in the late 1990s. We never learn.

Labor pains as inflation gains

So, my alternate explanation for the big Fed rate cut, if it was not due to electioneering, is that the Fed already sees more trouble for labor and the economy than it is letting on. So, it is gunning its 747’s mighty jets to make sure the plane, at least, makes it to the tarmac, instead of scoring a soft landing on some cushy San Francisco rooftops. (Of course, the Fed could be gunning its engines for both reasons.)

That brings us to the sticky part. The other aspect of how I’ve maintained all of this will fall down in the end is that, by the time the Fed needs to cut rates to boost the economy and curb rising unemployment as everything crumbles due to the Fed’s tightening, which reversed the effects of years of profligate free money, the Fed would find itself in a huge bind because it would be needing to stimulate the economy back to life just as inflation was ready to raise its head some more. The Fed would become caught in its own trap between all the inflation its former policies set into motion and the need to revive the economy it goosed along with those former policies because that economy would certainly fall apart when the Fed reversed its loose policies to tighten against inflation. The Fed would still be fighting inflation by the time the economy crumbled.

This was the always-foreseeable trap of the Fed’s policies—a badly stagflationary recession. The news says we have arrived there, too. Our ETA is NOW. The trap is set, if not already sprung:

Days after Rate Cut, S&P’s Flash PMI Sees Rising Inflation and Exhorts the Fed to “Move Cautiously” with “Further Rate Cuts”

Underlying inflationary dynamics are picking up steam, after having cooled a lot. Recently, S&P’s preliminary Flash US Composite PMI (Purchasing Manager Index) … entailed multiple warnings about the Fed’s future rate cuts, in light of reaccelerating selling-price inflation in both the services and manufacturing sectors, and in light of input-cost inflation in services….

“Prices charged for goods and services are both rising at the fastest rates for six months, with input costs in the services sector – a major component of which is wages and salaries – rising at the fastest rate for a year,” the report said.

“The “reacceleration of inflation” suggests that “the Fed cannot totally shift its focus away from its inflation target as it seeks to sustain the economic upturn,” the report said.

This is the stuff a short way up the pipeline that will soon discharge into consumer prices (CPI). The Fed’s big step toward looser policy (when interest wasn’t even high from an historic perspective) will help that inflation rise over time.