Well, they’ve done it again. Every year, the Biden Administration reports new jobs all year long that hit the sweat spot; then, after the measured year ends (from March to March in this case), they carefully count the jobs to make a correction of about half a million ghost jobs that never were and report it when hardly anyone is looking. Every year, the mistake results in a correction that is, of course, predictably downward. (You have to wonder about the same mistake being made every year.)

So, it is no surprise that they came up short again this year. We don’t know, yet, by just how much; but early news on the report puts the number around 600,000 or, in other words, about 50,000 more new jobs reported each month under Bidenomics than we really had.

For our purposes here, that means one important thing—confirmation of what I’ve been saying about the Fed and its broken labor metrics:

US job growth in the year through March was likely far less robust than initially estimated, which risks fueling concerns that the Federal Reserve is falling further behind the curve to lower interest rates.

In other words, as I’ve claimed all along, whenever the time came where the Fed would turn to cutting rates, it would be making its first rate cuts well into a recession.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Wells Fargo & Co. economists expect the government’s preliminary benchmark revisions on Wednesday to show payrolls growth in the year through March was at least 600,000 weaker than currently estimated….

Goldman Sachs indicates it could be as large as a million.

Now, that would be a wide miss, even compared to other Biden years or past administrations, which have tended to do the same thing. In other words, it would be an election-year size miss.

There are a number of caveats in the preliminary figure, but a downward revision to employment of more than 501,000 would be the largest in 15 years and suggest the labor market has been cooling for longer — and perhaps more so — than originally thought.

In other words, some years may have come close to 501,000; but anything over that is electioneering (in my never-so-humble opinion). Anything under that is the normal prevaricating of administrations that always want to make their new-job numbers look as robust as they can.

Of course, a labor market cooling for longer—perhaps more so—than originally thought (by the Fed) is an economy deeper in the cooler than originally believed … by the Fed … but exactly as believed here in The Daily Doom where we take our truth straight up without the seasoning of “adjustments.”

This news, of course, is likely to press the Fed all the more toward lowering rates in September, a move that could send inflation, which already has upward back pressure built up, right back up so that we can do the whole battle all over again because it was so much fun the first time. On the other hand, if the Fed avoids doing that, we dive deeper into recession. This is the trap I’ve said all along the Fed was setting up for itself … and for all of us because we have to go along for the ride of each rinse-and-repeat cycle. (Read: DOWNTIME: Why We Fail to Recover from Rinse and Repeat Recession Cycles.)

“A large negative revision would indicate that the strength of hiring was already fading before this past April,” Wells Fargo economists Sarah House and Aubrey Woessner said in a note last week. That would make “risks to the full employment side of the Fed’s dual mandate more salient amid widespread softening in other labor market data.”

It would mean the Fed’s labor gauge reading arrived more than late and that we may have been sinking into recession “before this past April.” The labor-gauge reading arrived after the end of the party.

The factors that led to overstated job gains are still present. Adjusted for business birth-and-death distortions, payrolls for April and July 2024 are the most likely to be revised to close to zero — well below a pace consistent with a neutral unemployment rate.

An article on NBC reports that suddenly …

More than 28% of Americans are searching for new jobs — the highest rate in a decade [and] people’s fears of losing their jobs are at the highest point in a New York Fed survey’s 10-year history…. Americans have rarely felt more in need of new job opportunities.

That’s the highest reading since March of 2014. If you’re looking for a job when numbers are that high, you may have to keep on walking.

That brings the stealth recession back up

It was as recently as June that the Philly Fed tingled the excitements of investors with news that the economy was strong:

The Philly Fed General Business Activity Index surged up into expansion at two year highs and there was much celebrating that 'soft' data was going to lead us out of a 'hard' data slump?

In other words, sentiment was soaring and would carry us out of any recessionary moves that had begun.

Well, that's all over now as the index crashed to -25.1 in August - its weakest since the COVID lockdowns.

Without seasonal adjustments, business activity crashed back down to levels not seen since the Covidcrash (-33, and with adjustments, it wasn’t much better at -25):

Those are already deeply recessionary numbers.

Under the covers, it was even uglier with future activity expectations plunging into negativity, capex expectations tumbling, and full-time employees crashing to their lowest since COVID lockdowns.…

Retelling the retail tale

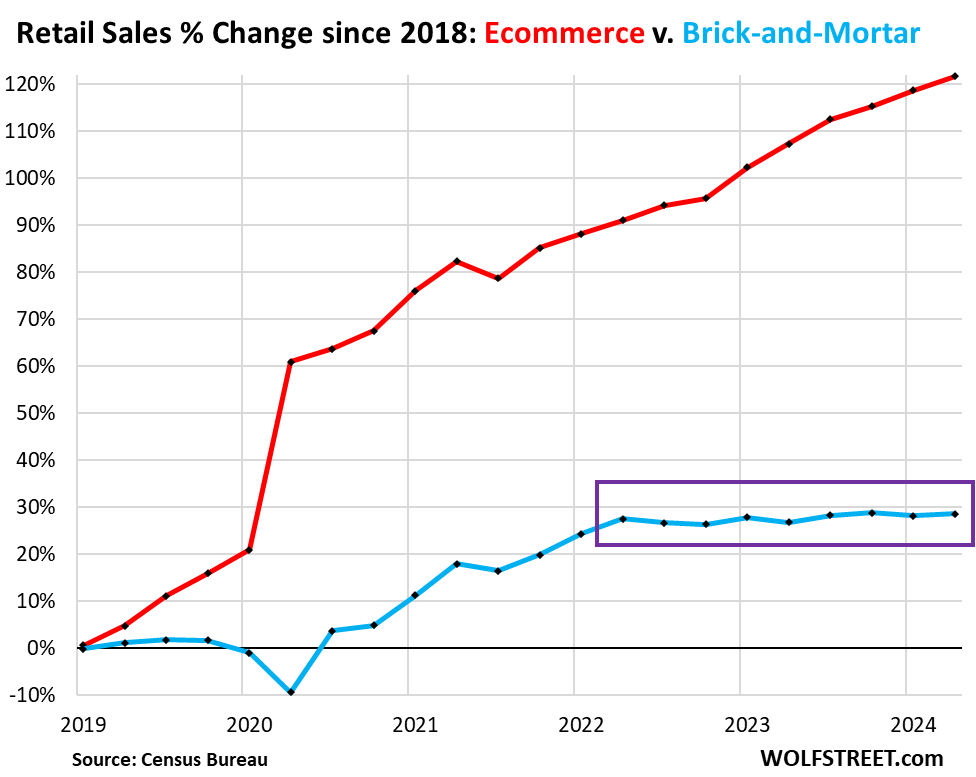

Finally, here is an overview of what the retail apocalypse has done to brick-and-mortar retail compared to electronic retail, to sum up what I was writing about recently:

Death by flatlining. Of course, the death of brick-and-mortar stores has a huge impact on surrounding neighborhoods and other nearby businesses, while the growth in online retail has none of that. It helps the online retailer, obviously, but does not bring traffic/commerce to anyone else—no one eating out, stopping to refuel, picking up some other odds and ends from nearby stores while in the area. Not much anyway. Maybe a little around the workers and robots at the online warehouse.

It is not that the change is a bad thing, but it is definitely a major economic hit to other businesses wherever it happens. In other words, we’re better off not to be driving so much in terms of our own expenses and environmentally and in terms of traffic congestion, but that doesn’t mean it does not have a big impact on the economy that must adjust over time.

The big stores, like Walmart, also wind up developing large e-commerce trade with large online platform; whereas, many of the smaller stores that were beside a former Walmart see very little traffic to their e-commerce sites and lose a lot of foot traffic when the local Walmart closes.

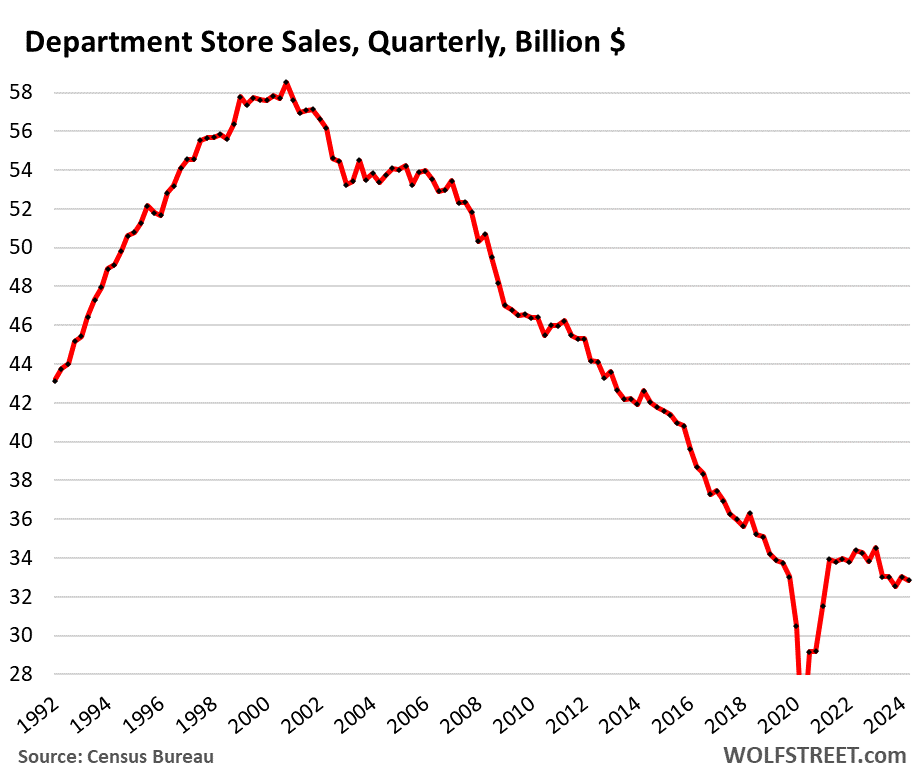

Many dozens of brick-and-mortar chain stores and countless regional chains and major independent stores that didn’t get the message about ecommerce and groceries – such as department stores – have collapsed into bankruptcy over the years and are gone, in a phenomenon that we’ve called since 2016, the Brick-and-Mortar Meltdown….

The prime example are department stores, which in 1992 (as far as the retail sales data go back to) accounted for 10% of retail trade sales. By July, the brick-and-mortar sales of the few surviving department stores accounted for just 1.8% of total retail sales.

There isn’t a thing in a department store that you cannot buy online. And the surviving department stores all have big ecommerce operations. Macy’s is one of the biggest ecommerce retailers in the US. But it keeps closing its brick-and-mortar stores.

E-commerce, of course, got a huge push from the Covid lockdowns, and it never slowed down thereafter or gave any of that back. Department stores, on the other hand, are the dinosaurs of our day:

And that’s without adjusting sales measured in dollars down for inflation!