If rising food prices are ruining your appetite, you’re not alone.

Costs of a number of grocery staples have been rising all year, including some that haven’t gone up in decades, such as peanut butter. Meats are seeing large increases, with the price of chicken climbing 8%, and pork and beef increasing about 5%.

According to Statistics Canada, via CTV News, two breakfast ‘staples,’ coffee and peanut butter have gone up significantly since January, a respective 17% and 6%. Canada’s Food Price Report predicts that prices will increase 5% this year, adding almost $700 to the average Canadian family’s grocery bill.

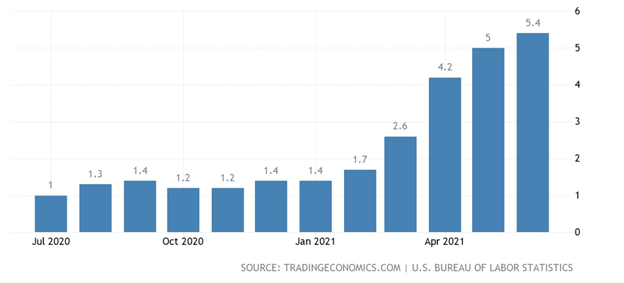

In the United States, US consumer prices hit their highest level in 13 years in May, jumping 5% from May 2020. The US Department of Labor says rising costs of meat products and baked goods led the surge in food prices.

“We’re in a period of unprecedented commodity inflation,” Unilever CEO Alan Jope told investors in early June.

According to Business Insider, US food prices are rising in tandem with broader inflation, with the CPI hitting 5.4% in June. Prices are climbing due to key commodities becoming increasingly difficult to obtain, shipping delays, labor shortages (for example in meat packing plants, hit hard by covid-19) and severe droughts in a number of countries (more on that below).

The US Department of Agriculture reports that so far in 2021, grocery prices have increased 1.6% compared to the same period last year, while the prices of restaurant meals and takeaways have risen 2.8%. The CPI for all food has crept up by an average 2.1%. Of all the grocery prices tracked by the USDA, the fresh fruits category saw the largest price increase, 5%, whereas fresh vegetables were the smallest at just +0.4%.

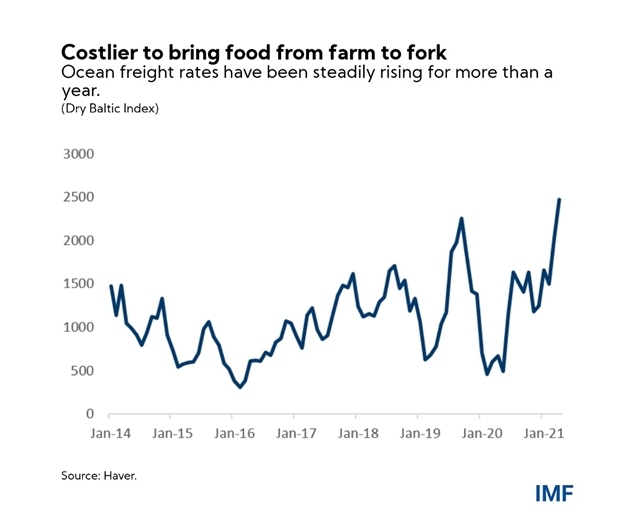

Adding to the cost of food is the price of freight. BI reports that a global container shipping shortage has made it difficult, and more expensive, to transport goods. According to Freightos, an online freight marketplace, shipping costs between Asia and the US have surged 250% from this time last year.

The International Monetary Fund said in June that ocean freight rates, as measured by the Baltic Dry Index, have increased between two and three times in the last 12 months. The IMF notes that more expensive gas, and truck driver shortages in some regions are pushing transportation costs higher, which are expected to eventually add to consumer food inflation.

Covid

The coronavirus pandemic has put tremendous pressure on supply chains, and the prices of many agricultural commodities such as grain, corn and soybeans, have skyrocketed. Because these commodities are used in animal feed, higher prices typically get passed down the supply chain to the cost of meats, including chicken, pork and beef.

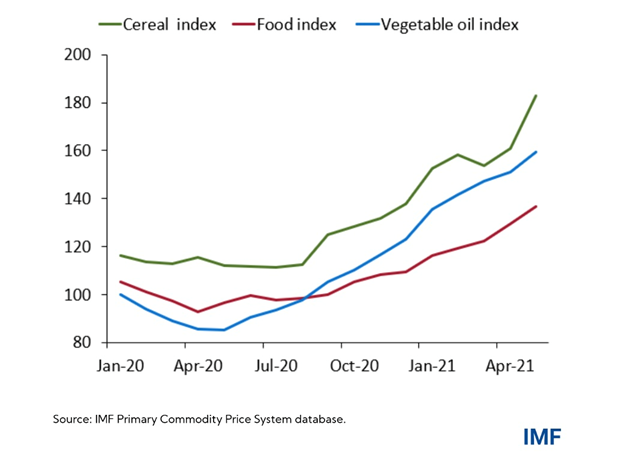

According to the United Nation’s food price index, in May global food prices rose for their 12th month in a row. The fifth month also saw the sharpest monthly rise in average food prices in over a decade, spiking 4.8% from April to May, CNN reported. The news outlet quotes a senior economist with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization stating that surprising demand for corn in China, an ongoing drought in Brazil and increased global use of vegetable oils, sugar and cereals has caused prices to surge rapidly around the globe.

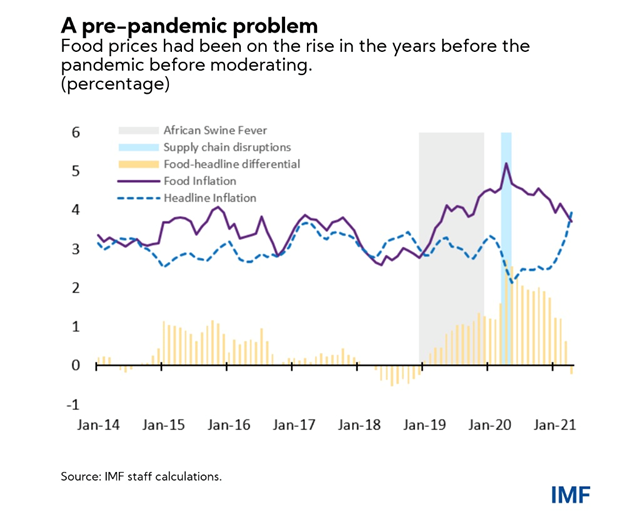

It’s tempting to place the blame on rising food prices squarely on the pandemic, however, in some sectors, rising prices predate covid-19. The IMF cites pork prices as an example:

In the summer of 2018, China was hit by an outbreak of African swine fever, wiping out much of China’s hog herd, which represents more than 50 percent of the world’s hogs. This sent pork prices in China to an all-time high by mid-2019 creating a ripple effect on the prices of pork and other animal proteins in many regions around the world. This was compounded by the introduction of Chinese import tariffs on US pork and soybeans during the US-China trade dispute.

The pandemic disrupted food supply chains by, for example, shifting the demand from food services (ie. dining out) towards retail grocery. Motivated by fear and uncertainty, shoppers forced to cook at home stockpiled certain grocery items like toilet paper, meat and pasta, leading to empty shelves.

While the prices of many foods have gone up, they may still have much further to go, because it typically takes six to 12 months, according to the IMF, for prices paid by consumers to reflect changes in producer prices.

The latter have reached multi-year highs, rising from their virus-related trough in April 2020 47.2% to their highest levels in May 2021 since May 2014. For example soybean and corn prices increased a respective 86% and 111%, year on year. The IMF states there are three factors behind skyrocketing producer prices: high demand for food staples and animal feed, especially from China, as countries stockpiled food reserves due to pandemic-related concerns about food security; the La Nina weather event in 2020-21 which led to dry conditions and poor harvests in key food exporting countries like the US, Brazil, Argentina, Russia and Ukraine; and strong demand for biofuels.

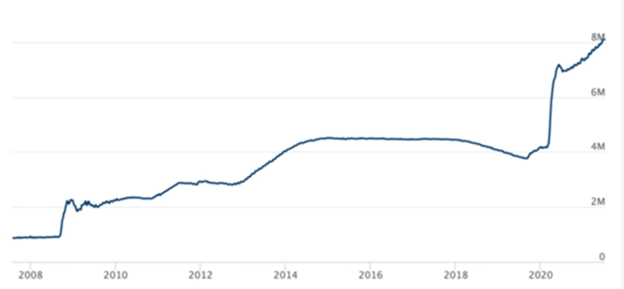

Again, the pandemic has certainly been influential in food price increases, but it would be a mistake to think that inflation will subside once the pandemic is over. US Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell has frequently said the current 5.4% inflation, way beyond the Fed’s 2% target, is transitory.

Powell, who attributes the high inflation rate to supply constraints as the economy re-opens, recently told reporters that “these bottleneck effects have been larger than anticipated, but as these transitory supply effects abate, inflation is expected to drop back toward our longer-run goal.”

Please tell me how an inflation rate that has risen from 1% a year ago, to 5.4% in June, can be temporary, when it has increased every month since December 2020?

US inflation, one year

US inflation, one year

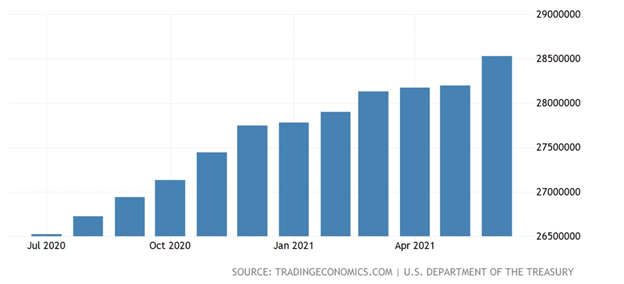

And here’s something you won’t read about in mainstream media. The Fed is severely constrained in how much it can raise interest rates, to quell rising inflation, due to ballooning debt. Following $4.5 trillion spent on pandemic relief, and trillions more to come, through Biden administration spending, along with the continuation of quantitative easing (what I like to call “quantifornication”) to the tune of $120 billion in asset purchases per month, the Fed has in one year doubled its balance sheet to around $8 trillion and the national debt currently sits at $28.5 trillion.

Total assets of the US Federal Reserve. Source: US Federal Reserve

Total assets of the US Federal Reserve. Source: US Federal Reserve

US national debt over the past year

US national debt over the past year

Interest paid by the federal government this year on its debt is estimated at just under $400 billion.

The Fed’s official line is that inflation is only temporary, however we see things differently.

Climate change

One of the most important factors driving food inflation is climate change. Global warming is obviously not a temporary phenomenon.

In 2018 the world’s leading climate scientists warned there are only 12 years to go for warming to be kept to a maximum 1.5 degrees C. If, after a dozen years, not enough is done to slow global warming, a tipping point will be reached, beyond which the risk of droughts, floods and extreme heat, will significantly worsen.

How are we doing with that? Not so great. One only has to look at regional climate/ weather maps to see that major changes are taking place before our very eyes.

The “heat dome” that covered much of western North America at the end of June, shattering temperature records, isn’t the only weather event making headlines. There have also been unprecedented rains followed by catastrophic flooding in China and Europe, and temperatures reaching 49 Celsius in normally temperate Finland and Ireland.

In Barrie, Ontario, a rare tornado designated as EF-2 (wind speeds up to 217 km/h) slammed into a residential neighborhood destroying homes and injuring 11 people. The twister was one of five recorded in southern Ontario.

We don’t have to wait years for the worst impacts of climate change to occur. They’re already here.

Despite the promises of politicians and certain business leaders who claim to have the answers to stop global warming, the truth is it is unstoppable. The world will keep warming until it starts cooling. We are all on an upward global warming escalator that has no down option. The only question is, how fast will the escalator move?

A 2017 research paper found that each degree Celsius increase would on average reduce global yields of wheat by 6%, rice by 3.2%, maize by 7.4% and soybeans by 3.1%. These foods provide two-thirds of human caloric intake.

A new study showed more than a fifth of global food output growth has been lost to climate change since the 1960s, putting an estimated 34 million people on the brink of famine.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota’s Institute on the Environment found that climate change is already shrinking food supplies, particularly rice and wheat. More importantly in terms of ameliorating global famine, an estimated 795 million people still regularly don’t have enough to eat.

Disturbingly, the study quoted by The Conversation found that rising temperatures have reduced consumable food calories by 1% a year for the top 10 crops – maize (corn), rice, wheat, soybeans, oil palm, sugarcane, barley, rapeseed (canola), cassava and sorghum.

Extreme heat and temperature fluctuations are hard on plants. Heavy rains on parched ground cause flooding, which can devastate crops and livestock, accelerate soil erosion and pollute water.

Droughts are exacerbated by rising temperatures, reduce crop yields and cause irrigation water shortages. Crops near coastal areas can also be ruined by saltwater intrusion as a result of storm surges or rising seas.

There are several examples of recent extreme weather events having a negative impact on food production.

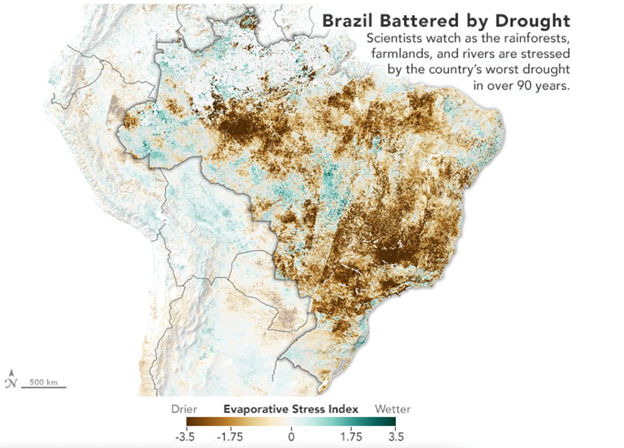

The most dramatic is Brazil, where a once in 20 years frost killed most of the young coffee trees in the world’s largest grower of the caffeinated beverage. In July, prices rose 17% and topped $2 a pound for the first time since 2014.

Talk about extremes. The country is also experiencing a once in a century drought that has depleted reservoirs needed for irrigation. According to government agencies, the drought which stretches throughout central and southern Brazil (see map below), is expected to cause crop losses, water scarcity and increased fire activity in the Amazon rainforest. Seven of 15 reservoirs are at their lowest levels since 1999.

The low river levels are also invoking fears of electricity rationing and higher bills — Brazil relies heavily on hydroelectric power for its energy.

Source: NASA Earth Observatory

Source: NASA Earth Observatory

In central Brazil, the worst water crisis in nearly 100 years has made navigation on one of the country’s most important river systems difficult, making it more challenging and costly to get its chief commodities exports to global markets. (June flows are @ 55% of the historical average)

BNN Bloomberg reports that Vale, a major iron ore producer,

is using low draft vessels on the river, and is also transporting ore by road and rail in a safe and legal way to reach clients in Brazil and abroad…

Globalization long ago did away with regional food markets; the ability to refrigerate and ship food thousands of kilometers away means that what happens in one country affects the world. This is particularly the case in Brazil, the top exporter of soybeans, coffee and sugar and the second biggest supplier of corn and iron ore.

The sprawling South American nation also accounts for around 40% of the world’s arabica harvest, the high-quality coffee beans known for their smooth flavor.

According to BNN Bloomberg,

The consequences of Brazil’s water woes stretch well beyond the borders of this Latin American nation, with receding waterways causing supply-chain disruptions and bottlenecks in Argentina, the world’s largest soy-meal shipper, and Paraguay.

NASA’s Earth Observatory says the dry weather is affecting the production of important Brazilian crops including coffee, corn, sugarcane and oranges. Yields for the corn crop could hit a five-year low and coffee production this year is forecasted to drop as much as 30% below normal levels.

In western Canada, rail cars carrying grain for export have been idled for weeks due to dangerous wildfires spanning five provinces and two territories.

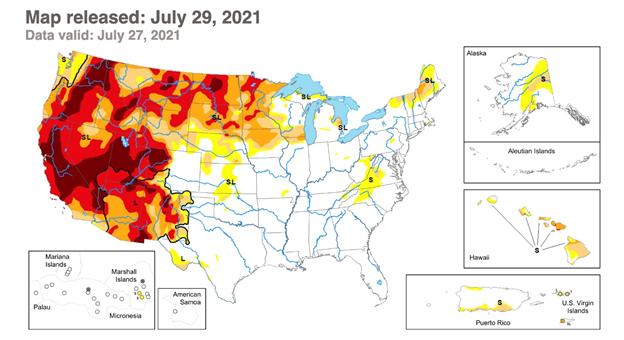

Drought conditions in the Prairies have withered crops and in the northern US, forced farmers to sell their low-yielding wheat and barley as livestock feed. The region’s spring wheat prices recently hit their highest level in more than eight years.

A 21-year drought in the southwestern US (and into the northern states including Oregon) is depicted in the latest map by US Drought Monitor. Red areas are extreme drought, brown areas show exceptional drought. The current dry stretch started in 2000 and hasn’t let up, putting it second only to a highly arid period in the last 1500s.

A recent article in the LA Times states that the world is facing unprecedented levels of drought, with nearly half of the US Mainland afflicted, and no continent except Antarctica spared. Besides the US and Brazil, other areas being subjected to drier than normal conditions right now include Madagascar, where hundreds of thousands of people have been left on the brink of starvation; and Mexico, which is releasing silver iodide into the clouds to stimulate rain.

Commodities

Climate change is affecting not only the prices of agricultural commodities and food, but the entire commodities complex. As global temperatures warm, practically everything that is grown or mined is impacted.

Many are pointing to the formation of a new supercycle, driven not by fossil fuels and the rise of China, such as occurred in the early 2000s, but by so-called “green” metals needed to electrify and decarbonize, to avoid the worst effects of climate change.

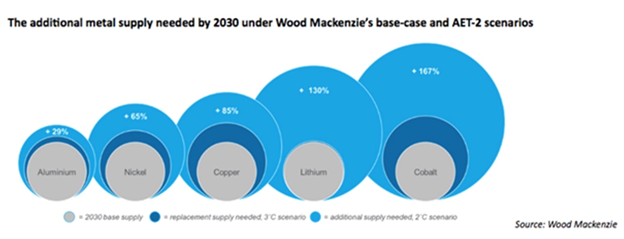

A recent report by Wood Mackenzie says that limiting a rise in global temperatures to 2 degrees Celsius, the target agreed to at the 2016 Paris climate summit, will require an additional 360 million tonnes of aluminum, 90Mt of copper and 30Mt of nickel over the next 20 years.

The report predicts by 2030, cobalt producers will have to add 167% more supply, ie. more than double the 140,000 tonnes per year of the battery metal currently mined. For nickel it’s a necessary 65% increase, for copper it’s +85%, and for lithium producers, 130% more supply needs to be found and extracted, either through hard rock mining, brine operations or clays.

An earlier report from the Scottish commodities consultancy found that mining companies will need to spend $1.7 trillion over the next 15 years, to supply enough lithium, graphite, cobalt, copper and nickel for the shift to a low-carbon world.

On top of surging demand for metals needed to feed so-called “green infrastructure” programs, we have current and emerging structural deficits for several metals, that will keep prices buoyant for the foreseeable future.

These metals were already under supply constraints even without a clean energy transition. Tight supply was reflected in the rising prices of copper, nickel, zinc, for example, before covid.

Along with government-led programs to electrify and decarbonize, pushing demand for energy/ battery metals higher, a dearth of exploration spending in recent years to develop new deposits, and the compounding/ cascading effects of climate change we have resource nationalism.

Resource nationalism is the tendency of governments to assert control, for strategic and economic reasons, over natural resources located on their territories. It has been identified as one of the key risks for investors in the natural resources space.

With the copper price soaring on tight supply and heavy demand, as the world’s biggest economies revive following over a year of coronavirus-related restrictions, the temptation for producer nations to cash in on more valuable copper reserves to pay for social programs is proving hard to resist.

Chile and Peru, the number one and two producers, are both seeking to raise the royalty tax on copper miners, while in the DRC, Africa’s top copper-mining country, the government has slapped a ban on the export of copper and cobalt concentrates — an action almost identical to what has happened in Indonesia with nickel.

Adding to these events, workers at BHP’s Escondida copper mine in Chile — the largest in the world — and two smaller mines, Codelco’s Andina and JX Nippon Mining & Metals’ Caserones, are threatening to strike, fueling concerns about the short-term supply of the ubiquitous industrial metal.

Bloomberg reports up to 7% of world copper production hangs in the balance, including around 1.2 billion tonnes from Escondida, representing 6% of global supply.

The South American nation is fast becoming a liability for copper miners.

Triggered by the worst social unrest in a generation, anchored in rampant inequality, the country reportedly has just elected an assembly that will place responsibility for writing a new constitution in the hands of the left wing.

The reforms could give more power to indigenous communities and expand water rights, including a potential ban on mining in areas where there are glaciers, along with increased state ownership of water desalinated by mining companies.

There is also proposed legislation that, if approved by the Chilean Senate, would impose a royalty as high as 75% on sales of copper, if copper is above $4 like currently.

Earlier this year Goldman Sachs said the new law could put at risk 1 million tonnes of annual copper supply representing about 4% of global output.

The investment bank clarifies that more than half of foreign-owned copper mines in Chile have tax agreements in place that don’t expire until 2023, but future mines would be in jeopardy.

“All else equal, we believe fiscal uncertainty will act as an overhang on mining companies’ decision-making processes to sanction new projects, which could further exacerbate our expectations of a longer-term copper supply gap,” Goldman Sachs said.

A Reuters story adds that while Chile mines close to a third (28%) of the world’s copper, for more than a decade it has lost market share, “hobbled by declining ore grades and ageing projects.”

The Congolese government’s decision this year to ban the export of copper and cobalt concentrates shows that resource nationalism is alive and well in the African copper belt. The DRC and Zambia are the continent’s top two red metal producers, in 2020 outputting a respective 1.3 million and 830,000 tonnes.

As mentioned the prices of a number of industrial metals have risen this year due to a constellation of factors, including robust demand from China whose post-pandemic recovery is fueling an economy that grew at 12.7% in the first half of 2021.

Last week BMO Capital Markets raised its second-half price estimates for most base metals. The prices of nickel, aluminum, zinc and lead were adjusted upward by 7-8%, while for iron ore, BMO slowed the pace of its forecasted decline.

Price increases in raw materials may not be felt directly by consumers, but it is only a matter of time before higher input costs are reflected in retail sticker prices. A good example is aluminum. Bloomberg reported on Monday that Heineken, the world’s second largest brewer, says the rising costs of freight and beer cans are likely to weigh on profits next year, following a 30% year to date rise in the price of the lightweight metal.

Another major aluminum user, Reynolds Consumer Products, said it is facing an extra $400 million in costs this year, due in large part to more expensive aluminum and resin needed to make its iconic Reynolds Wrap.

Conclusion

Just about everything is going up, from agricultural commodities needed to grow food, to groceries, restaurant meals, industrial metals and consumer products that are made from hard-to-source metallic compounds.

The prevailing trend is to blame the pandemic on rising inflation, and to some extent this is correct. Workers sidelined by covid-19 are making it more difficult for factories to schedule shifts and run efficiently. The US economy faces a shortage of workers, driving wages and salaries higher. A lack of affordable child-care and fears of contracting the coronavirus are keeping many workers, mostly women, at home. Republicans blame the Biden administration’s enhanced unemployment benefits, including a $300 weekly check, for providing a disincentive for returning to work. The same thing is happening in Canada with the overly generous CERB.

There is a global micro-chip shortage affecting several industries including automaking, brought on in part by the surge in PC sales that has accompanied working from home.

Countries have stockpiled food reserves due to concerns about food security, leading to higher prices of agricultural commodities.

But covid-19 only tells a small part the story of inflation, which at its current 5.4% level, is ringing alarm bells, or should be.

A large increase in the money supply is another factor. Consider: “quantifornication” is still going on in the US, Britain and the EU, meaning that excessive money-printing is continuing to devalue currencies at an alarming rate (this, by definition, is inflation, because it takes more units of currency to buy the same amount of goods as before).

Trillions more in economic recovery spending is promised, with little concern over the mounting debt pile. A few weeks ago the Wall Street Journal reported that the pandemic has pushed global debt to the highest level since World War II, surpassing annual economic output. Despite a budget deficit of $3 trillion for the second year in a row, and fear of inflation, the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield is only 1.19%.

Central banks are having to walk a tight rope between keeping rates low enough to keep economic growth going after more than a year of virus-caused economic pain, and stopping inflation from getting out of hand.

As countries continue to recover from the low-growth months of the pandemic, trillions of dollars in pent-up demand are poised to push inflation even higher. In the United States alone, households have accumulated at least $2.5 trillion in excess savings.

In the second quarter, Reuters reported that consumer spending grew at a blistering 11.8%, accounting for much of the the economy’s 6.5% growth pace. Spending is surging as more Americans (and Canadians) get vaccinated and return to pre-pandemic purchasing levels.

Supply constraints, structural deficits, in certain industries plus greater demand for goods and services is also a recipe for higher inflation. To the question of whether inflation is temporary, we are seeing increasing evidence it is not, ie., that rising prices are becoming a permanent fixture of the economy.

Climate change is providing an unexpected floor for prices particularly with respect to agricultural commodities. Droughts in the “breadbaskets of the world” including the United States and Brazil, are to blame for lowering yields and bumping up prices. Brazilian crops likely to be affected include coffee, corn, sugarcane, and oranges.

Resource nationalism is the tendency of governments to assert control, for strategic and economic reasons, over natural resources located on their territories and across the world it is rearing it’s ugly head. It might be mandated benefaction within country, a greater percentage of mine ownership, higher taxes or a combination of the three. Increasingly resources are being being used for political blackmail.

BNN Bloomberg reports that commodities as a whole have risen more than 20% this year and 50% for crude oil, with the Bloomberg Commodity Spot Index at a decade high and heading for a fourth-straight monthly increase.

According to United Nations data, food prices have risen for all but one of the past 13 months and now stand at their highest since 2011.

The higher input prices are taking their toll on end users, including a trade group representing some of America’s biggest baked good companies.

According to AgWeb Farm Journal, the American Bakers Association is urging the Biden administration to dial back its biofuel quotas, because fuel made from crops like soybeans and canola could increase the cost of donuts and breads. Around 40% of US soy oil consumption goes to producing fuel, with the rest going into food.

Pandemic-related supply constraints might be temporary and money-printing and currency devaluation could be transitory, although they are likely to be with us for at least the next two years.

Structural supply deficits, climate change, the global trend to electrify and decarbonize, and resource nationalism are not temporary or transitory.

The inescapable conclusion? Inflation compounds year after year and the purchasing power loss your currency has experienced will never be regained.

Inflation is going to continue – you better be prepared for scarcity, a lack of security of supply, and much higher prices.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.