- No Blank Slate

- Running Hot

- Major Adjustment

- What Really Caused Inflation

- The Fed’s Real Dilemma

- Washington, DC, and Home for the Holidays

You won’t be surprised to know I disagree with recent Federal Reserve policy choices. The Fed’s future choices are more important, though. Debating what they should do is one thing. Anticipating what they will do is critical.

Today we’ll “war game” what the Fed is facing as it wrestles with inflation, growth, employment, and political considerations. We’ll try to entertain those thoughts as if we’re sitting in the conference room with Jerome Powell.

In understanding the Fed’s thinking, it’s important to remember monetary policy is an iterative process. The Federal Open Market Committee members never get a blank slate. They can’t wipe the economy clean and start over. Choices their predecessors made years and even decades ago govern what they can do now.

For example, the Fed’s decisions in 2008–2009 to drop short-term rates to near zero and then launch quantitative easing bond buying programs were unprecedented at the time. But they “worked” well enough to keep the wheels on. The economy survived. That being said, correlation is not causation. I maintained then and I believe now that the recovery was due to businesses, both small and large, adapting to the new climate. Federal Reserve policy was a distant second.

But the problem is, Fed officials thought their policies were responsible for the recovery. When COVID happened, the 2020 Fed had a “playbook” to follow—even if it was based on false premises and correlations.

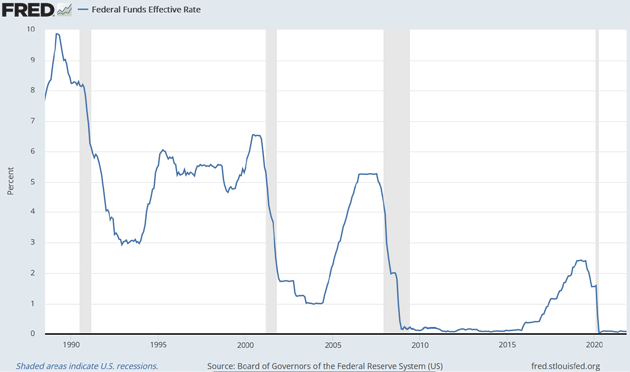

But those 2008–2009 decisions also didn’t come from nowhere. In the early 1990s and again in the early 2000s, Alan Greenspan’s Fed had responded to recessions with sharp, aggressive rate cuts. Those “worked” too, and Greenspan even managed to tighten again afterward. Fed officials in 2008 no doubt looked back at those years and figured they could get away with it, too. (Again, inward-looking and massively biased Federal Reserve economists believe their policies and not the individual actions of businesses caused the recoveries.)

Source: FRED

But the process doesn’t always go where they expect. Previous Fed leaders raised rates because their rate cuts had the desired effect of spurring growth and sparking inflation fears. But post-2009 GDP growth, while positive, was nothing like previous recoveries. Inflation (at least as the Fed measures it) also failed to show up on schedule. Bernanke and then Yellen, looking at the playbook, thought as early as 2013 they were “supposed” to tighten policy, but the data at the time didn’t support it. Perhaps more important, Wall Street didn’t support it, either. Remember the multiple taper tantrums?

So the Fed waited and waited, finally taking a tentative first step in 2016 and then a series of rate hikes and asset purchase reductions in 2016–2019. It didn’t have the desired effect and seemed to cause other problems. So, in a move we now forget amid the other noise, the Fed began easing in late 2019—months before COVID was known.

Imagine, then, you are Jerome Powell in early 2020. You’re already struggling to deal with massive debt, bond market liquidity issues, and stagnant growth. Then you get hit with simultaneous global supply and demand shocks.

But that’s not all. To keep the wheels on, you need Wall Street banks to cooperate and help you finance the government’s large and growing debt. Otherwise, rates will spiral higher. Even worse will follow. In theory, you are their regulator, but it’s not entirely clear who has more power. The Fed can force money into the system. It can’t force banks to buy Treasury debt or lend to consumers and businesses.

But that’s not all the Fed is thinking.

Until quite recently, inflation was exactly what the Fed wanted. They spent years trying (and failing) to generate more of it. Officials spoke of “running the economy hot” for an extended period to get long-term inflation averages back on target.

Well, that’s what is happening. The economy is hot, or at least hotter than it was, balancing those below-average inflation years with an above-average one. This isn’t because the Fed did anything right. It’s arguably a result of their other mistakes. But if you had shown them today’s inflation numbers a couple of years ago, I bet more than a few FOMC members would have said, “Yep, that’s ideal.” (Please note, I don’t endorse that view. I’m just describing how they think.)

I have been in a room where multiple Nobel laureates endorsed letting the economy run a 4% inflation rate. I and some of my fellow participants in the conference were staggered at the lack of understanding of how the real-world Main Street works.

So Fed officials are in an odd position. They’re getting what they wanted and most everyone else hates it. What do you do in that situation? The strategy appears to be, “Talk tough and drag your feet.” The present taper plan, even if they pick up the pace, isn’t tightening anything. The Fed is still stimulating (or trying to) at a somewhat slower pace. They are a long way from neutral, and when/if they reach neutral will be a long way from anything fairly described as “tight” policy.

But the other piece of this is also interesting. The Federal Reserve’s main tool is its credibility. Everyone knows about its financial firepower. The wild card is whether it will use that firepower… particularly when lots of powerful people don’t want it to.

One consequence of inflation is that it pushes “real” interest rates lower. Depending on your benchmark, short-term USD rates are now around -6%.

If the Fed follows recent practice and raises rates a quarter point at each meeting starting in mid-2022, it might add up to a 1.25% hike by the end of next year. If inflation does what I think it will do, that will still leave negative real interest rates of -3%, still extraordinarily accommodative. But would markets tolerate anything tougher? Probably not.

This is the corner the Fed is painted into. They would have to stop their asset purchases and raise the Fed Funds rate 300 basis points or more just to get real rates to 0%. Doing so would generate a taper tantrum on steroids. Does Jerome Powell have the stomach for it? Color me skeptical.

Nor is this just perception. It would have real-world consequences. Most obviously, higher rates would raise borrowing costs for the biggest borrower of all, the US Treasury. The debt has reached a size at which even tiny rate increases add big bucks to the government’s bill.

Nor would other borrowers be untouched. Think of all the mortgages, business credit lines, credit cards, car loans, and more tied to Treasury yields, the prime rate, or other such benchmarks. Real yields might still be negative but higher rates would still reduce liquidity and might push some overleveraged borrowers (of which we have quite a few) into default.

It’s also an open question what would happen to the yield curve in this scenario. If the Fed hikes short-term rates and money moves from stocks into longer-term Treasury bonds, we could be looking at an inverted yield curve soon thereafter. Banks would then stop what little lending they are doing now, which wouldn’t be good for debt-dependent consumers, businesses, and others who rely on the first group. That’s a really good way to trigger a recession.

Jerome Powell knows all this. The last thing he wants is to have shepherded the economy through COVID only to send it into a deep recession. I’m sure he will try to thread the needle somehow, but the odds are against him.

So where does it lead? I think Powell will keep trying to jawbone inflation down without doing anything to upset the market applecart. It will work for a while, too. But if the supply chain snarls continue and energy prices stay elevated (neither of which Powell can do much to change), inflation won’t come down much.

At some point, the narrative will change to “Powell the Powerless,” which is something no Fed chair can abide. We may then see the Fed clamp down hard and fast, triggering a serious market downturn. How serious? No one knows, but a 20% to 30% drop in the S&P 500 is entirely possible. That is plausibly just “letting the air out” of the bubble. Small speculators (the Robinhood crowd) will get hurt but others will hold steady. The question is will Powell reward them for doing so when he takes his foot off the brake and markets soar rather than waiting for inflation to come back to 2%?

If he does favor Wall Street over Main Street, the cost of doing so will be more inflation, which, as noted, is what the Fed really wants anyway. I think Powell believes the disinflationary era is over, at least for a few years. The China-led globalization that kept goods prices low for the last 20 years has mostly run its course. Add in demographic-driven labor shortages and we seem set for a meaningful trend change.

That’s not to say hyperinflation is coming. A world of 5% inflation isn’t necessarily a catastrophe. It was that high or higher for most of my early career. But after decades of 2% or lower CPI, and the correspondingly low interest rates, 5% will be a major adjustment.

Here’s the problem. The inflation that the Fed is supposedly fighting was not caused by them and their tools are insufficient to fight it. Admittedly, zero-level interest rates caused high prices in car loans, used cars, and homes. Raising rates will take care of those problems, but given how the Fed measures inflation, the prices in those markets coming down will not significantly impact inflation.

Quantitative easing? It has an effect on housing but it is more of an impact on asset price inflation especially the stock market and the entire financial system. Quantitative Easing is a massive stimulus program for Wall Street and the stock market, etc. It does nothing for the bottom 60–70% of Americans.

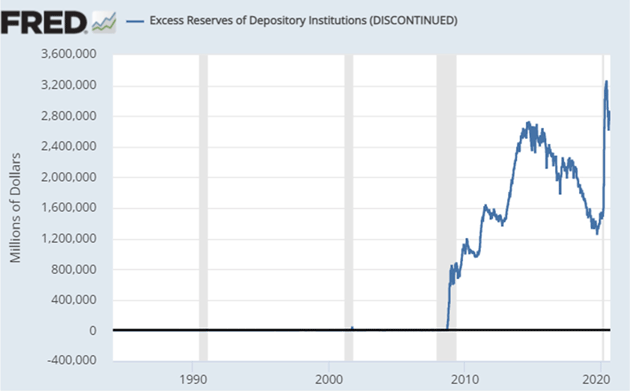

In the “olde days,” when the Federal Reserve would change reserve requirements for banks, that had an impact. Banks are required to have a minimum reserve deposited at the Federal Reserve. Anything above that is called “excess reserves.” Now, a prudent banker would want to have a certain amount of excess reserves. But since excess reserves paid nothing back in ancient times, a prudent banker also would want to try to lend that money out. Today banks are paid a minimal amount for their excess reserves. All that quantitative easing that began in 2009? It ended up back on the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve. It did not cause inflation, which all the Austrians (you know you are) were declaring would be the end of the world in 2009. I had multiple debates in public on that topic and I told everyone of them they were wrong. I’ll take a victory lap here, I got it right.

The chart below makes my point. You can go to the source at the St. Louis FRED database and find that excess reserves were under $1 billion in the ‘80s and ‘90s. (Scroll along the flat line and you can actually get numbers.) Now excess reserves are in the neighborhood of $3 trillion.

Source: FRED

What happened? Two things. First, banks ran out of creditworthy borrowers as defined by the regulatory groups that oversee them. Second, regulatory scrutiny severely crimped the ability of small banks to lend into their neighborhoods. Farmer Jones needs a new tractor? The local banker knew whether they could repay. Farmer Smith might not get the same deal. But regulatory agencies don’t recognize the ability of the neighborhood banker to differentiate between Smith and Jones. So they can penalize the bank for lending to Farmer Jones. Regulators want to see balance sheets that can pass their scrutiny. Thus banks, small and large, are not lending to Main Street in general. Big public companies, and even small ones, can go directly to market and sell bonds that are less expensive than borrowing from a bank. The banking business has changed big time.

Quantitative easing changed almost nothing but asset prices in the financial markets. Low interest rates affected, again, car loans and mortgages. That is all on the Fed.

But actual inflation? That’s all on fiscal policy and Congress. The Federal Reserve can accommodate Congress with buying government debt, but that shows back up on their balance sheet. It is not “hot money.”

The multiple stimulus packages Congress passed were hot money squared. It went into the hands of people who actually spent it. And since they couldn’t buy services like restaurants, hotels, and travel they bought “stuff.” So we had a “demand shock.” Consumers wanted more than businesses could produce.

But wait, there’s more. COVID seriously impacted supply, too. When your employees can’t come to work shortages start to build up rather quickly (think lumber, chips, etc.). Further, businesses were facing wage inflation and higher costs for their component products. They raised prices, sometimes because it was justified and sometimes simply because they could. Note that profit margins for the largest companies in the US are at all-time highs. It’s not any different than smaller companies. $10–$12 per pound for bacon? A $23 pastrami sandwich in Boston? There are literally thousands of such anecdotal stories.

Cummins Diesel says that they will be dealing with chip shortages for another two years. They’re buying run-of-the-mill, low-end chips. Chip fabricators do not want to build a factory to manufacture low-end chips when the demand will not be there two to three years from now. They need to see 10-year horizons. That is the same for multiple businesses all across the spectrum. Businesses can see an initial demand created by massive stimulus from Congress, supply chain disruptions caused by COVID, and realize that things will settle out and building another production line today will not be useful when demand evens out two years from now. It’s just going to take time to sort through the demand and supply shocks.

And there is nothing the Federal Reserve can do with their policy tools that can fix the cause of inflation created by Congress. But as I said at the beginning, they don’t get to wipe the slate clean. As my dad would say, you have to play the cards you are dealt (well, he actually said that about dominoes but you get the drift).

I am not certain what the Fed will do, but what they should do is draw down quantitative easing much quicker than any of us anticipate—in 4–5 months max. Then they need to start raising rates. And they need to keep raising rates until inflation is under 2.5%. They cannot repeat the mistake that Arthur Burns made in the ‘60s and ‘70s by letting inflation run hot because he thought it was transitory. Ultimately, the cure for high prices is high prices. Inflation will, if not accommodated by the Fed and Congress, recede and we will be back to a disinflationary/deflationary environment.

I don’t think Congress is going to pass another massive stimulus bill. I have listened to Senator Joe Manchin give at least six presentations (both private and public) plus his written record, and he doesn’t sound like he intends to move much. Manchin has said repeatedly that he wants to see inflation coming down before he signs on to another bill. Some in Washington think Manchin is playing “rope a dope” and hoping the BBB will die of its own accord.

Jerome Powell’s problem is that Wall Street won’t like a reduction, much less a cessation of quantitative easing. Higher interest rates are not conducive to the ongoing financialization of everything.

There is a very real possibility, if not probability, that the stock market enters a bear market in 2022 while inflation remains high. It could happen before the Fed raises rates. What does Powell do then? Does he fight inflation, as the Fed’s mandate says he should, or follow recent precedent and accommodate the markets?

By continuing to fight inflation he risks a mild recession. We’re not talking 1982 and Volcker. More like 1991, which the markets shrugged off after a year and continued on into a bull market. A mild recession will solve the inflation problem then Powell can come riding to the rescue.

Powell’s mistake was not ending QE and raising rates in late 2020 when the economy was clearly getting stronger. The Fed has already made its policy error. Congress also made a massive bipartisan fiscal policy error, even if well-intentioned.

To compound the problem, COVID has changed the employment market significantly. Many people have simply decided to not be part of the labor force, because of retirement or for personal reasons. We have spiraling wage inflation, which is real and sticky and is not going away soon.

It will be a massive policy error, much more extreme than the last one, if the Fed doesn’t lean into inflation even if the stock market suffers a short-term retreat. What have we learned over our last 50 years? The market comes back and will be stronger and higher. Valuation will matter.

But not if the Fed lets inflation really take hold. Jerome Powell clearly knows the history of Arthur Burns and his successor, William Miller, screwing up. Here’s hoping that Powell is made of sterner stuff.

Washington, DC, and Home for the Holidays

My next scheduled trip is Washington, DC, in mid-January. Brrr. I know I will want to go to New York a few times and potentially Las Vegas in March. Other than that, Shane and I will be home for the holidays, which in our neighborhood in Puerto Rico is actually fun. Lots of parties during this time and Shane and I intend to throw our own on January 1 with a black-eyed peas and cornbread Southern-style festival. If you’re in the area, it is an open invitation to my friends and neighbors. Shane and I did this regularly in Dallas and would entertain upwards of 150 people.

Black-eyed peas are a Southern tradition. The superstition is that you get one day of good luck for each black-eyed pea you eat on January 1. Growing up, that was a problem, because in all honesty? My mother couldn’t cook black-eyed peas that were palatable. I hated them. But in the last decade, Shane and I have learned to really spice them correctly. You have to throw in lots of bacon and ham. Add jalapeno cornbread? Yum. Honey baked ham, a little chili? Lots of friends and neighbors? It just makes for a good day.

Finally, on a sad note, my friend Dave Draper passed away at 79. He was known as the Blond Bomber, the Mr. Universe with the massive back right before Arnold Schwarzenegger. I have pictures of the two of them training together. His book, Brother Iron, Sister Steel, is a classic telling of the heyday of Muscle Beach in Venice, California. He was a fabulous storyteller and an inspiration to everyone who met him. Rest in peace, my friend. And I know that we owe you a few more reps in the gym.

With that, I will hit the send button. Here’s hoping that 2022 will allow for a lot more travel to see friends and family. Have a great week! And follow me on Twitter!

Your worried that inflation is more than transitory analyst,

|

|

John Mauldin |

P.S. Want even more great analysis from my worldwide network? With Over My Shoulder you'll see some of the exclusive economic research that goes into my letters. Click here to learn more.