Lower interest rates and massive asset purchases by central banks are the monetary tools of choice when it comes to restoring shocked financial systems. The idea being that making the cost of borrowing cheap for individuals and businesses will entice them to spend, spend, spend.

Quantitative easing is a technique used by the US Federal Reserve and other central banks to stimulate the economy in times of crisis. The Fed buys up securities from its member banks, thereby adding new money to the economy (this is where the expression, the Fed is “printing money” comes from). It’s a way of funding new expenditures, without actually dipping into the federal budget.

The idea is to free up more money for banks to make loans to individuals and businesses, thus growing the economy. The money is not cash, but credit that is added to banks’ deposits. When it wants to print money, the Fed lowers the benchmark federal funds rate, and banks in turn lower their interest rates, making capital more affordable so that businesses and investors are more likely to borrow.

The Fed used quantitative easing in the wake of the 2008-09 financial crisis and it did so again in 2020 to deal with the coronavirus pandemic. QE was successful in preventing a financial meltdown during 2008 and 2020, but the effect was a reliance on cheap credit that fueled both a stock market bubble and a real estate bubble. Bond investors also became addicted to Fed stimulus. This is because during QE, government bond yields dropped to near 0%, however this also meant that bond prices stayed elevated. Bond yields and bond prices move in opposite directions.

After the pandemic, the Fed’s monetary policy shifted 180 degrees and it moved to quantitative tightening and a cycle of interest rate hikes that have only recently leveled off.

Since June 2022, the central bank has been shrinking its asset holdings, mostly Treasuries and mortgage bonds. According to Bloomberg, the current pace allows a maximum of $60 billion in Treasuries and $35 billion in mortgage-backed securities to mature every month without replacement.

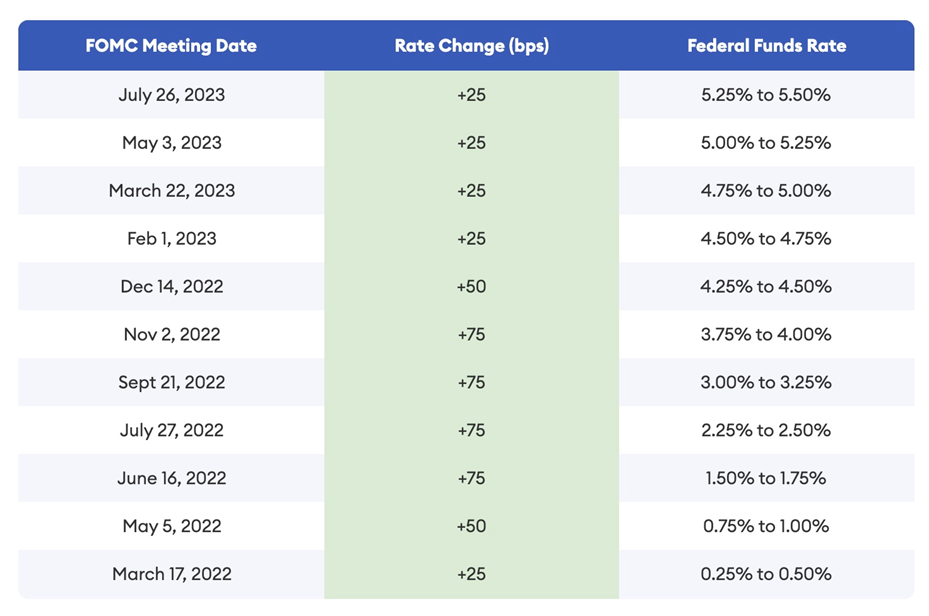

Between March 2022 and July 2023, the Federal Reserve lifted interest rates 11 times to the current range of 5.25-5.5%, to quell inflation that had risen to 40-year highs — the combination of monetary easing by the Fed and high government spending during the pandemic including direct stimulus payments to Americans.

Source: Forbes

Source: Forbes

Global debt back on the rise

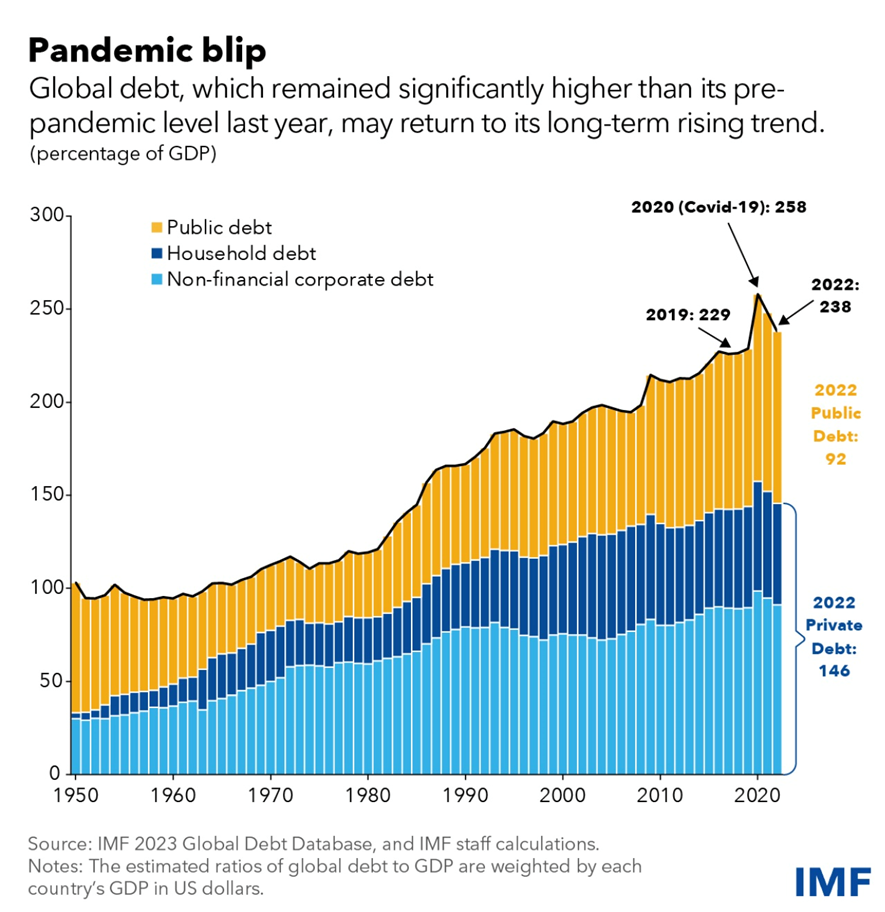

The global debt burden retreated in 2022, however it remains above pre-pandemic levels, states the latest (October) update of the IMF’s Global Debt Database. Total debt stood at 238% of global GDP last year, nine percentage points higher than in 2019.

Source: IMF

Source: IMF

An IMF blog post reports that despite economic growth recovery from the pandemic and higher-than-expected inflation, which reduces the “real” value of debt (see section below on inflating away the debt), public debt remains stubbornly high:

Fiscal deficits kept public debt levels elevated, as many governments spent more to boost growth and respond to food and energy price spikes even as they ended pandemic-related fiscal support.

According to the IIF (Institute of International Finance), global debt reached a staggering $307 trillion in the third quarter of 2023, with big increases in both mature markets (US, Japan, France, UK) and emerging markets (China, India, Brazil and Mexico). In a report, the financial services trade group said global debt in dollar terms rose by $10 trillion in the first half of 2023 and by $100 trillion over the past decade. It said the global debt to GDP ratio is now 336%, having risen for two straight quarters. Before 2023, the ratio declined for seven quarters.

“The sudden rise in inflation was the main factor behind the sharp decline in debt ratio over the past two years,” the IIF said. The report also stated more than 80% of the debt buildup came from the developed world, noting that “As higher rates and higher debt levels push government interest expenses higher, domestic debt strains are set to increase.”

Household debt to GDP in emerging markets was still above pre-pandemic levels largely due to China, Korea and Thailand.

While public debt declined by 8% of GDP over the past two years, it only offset about half of the pandemic-related increase, according to the IMF’s numbers. Private debt, which includes household and non-financial corporate debt, fell by 12% of GDP, again not enough to erase the pandemic surge.

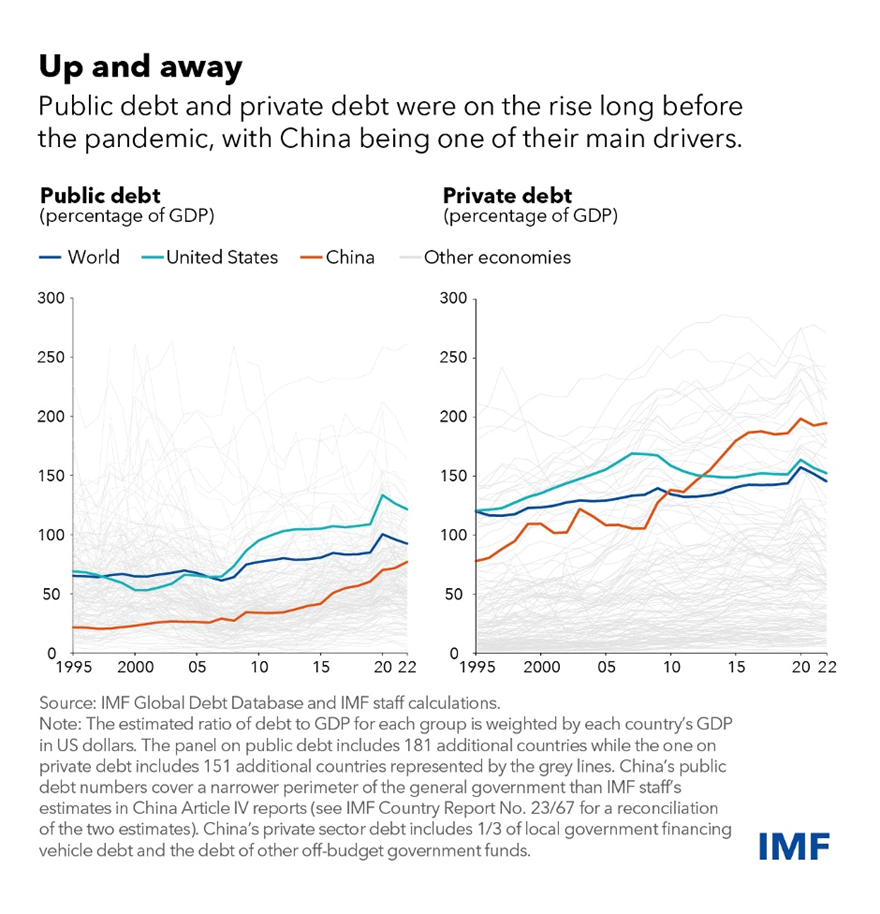

The IMF observes that before the pandemic, global debt to GDP ratios had been rising for decades, with public debt tripling since the mid-1970s to reach 92% of GDP by the end of 2022. Private debt also tripled to 146% of GDP but over a longer time span, between 1960 and 2022.

Also, while much has been written on China’s increasing debt, the IMF notes that while China’s debt to GDP ratio has risen to about the same level as the United States, in dollar terms its total debt is markedly lower, at $47.5 trillion compared to the US’s close to $70 trillion. However, China’s 28% share of non-financial corporate debt is the largest in the world.

Source: IMF

Source: IMF

US debt debacle

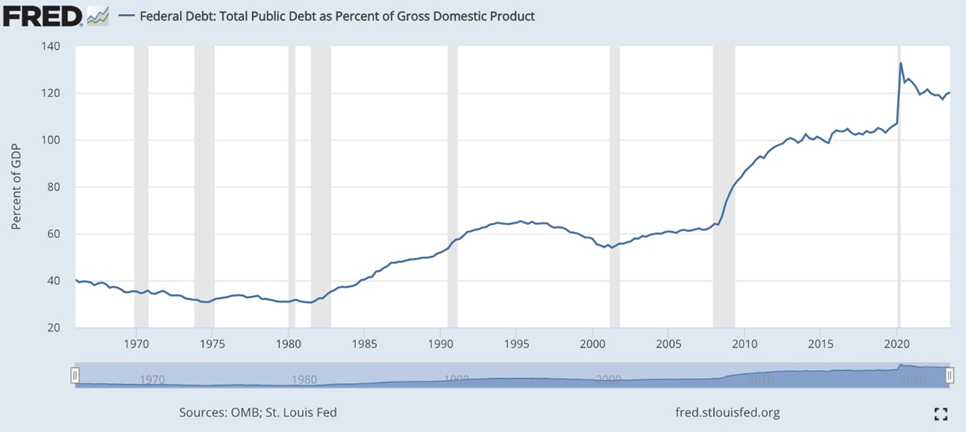

The United States has the world’s highest national debt in dollar terms, but Japan’s is higher in terms of GDP — 258% versus the US’s current 120%.

Source: FRED

Source: FRED

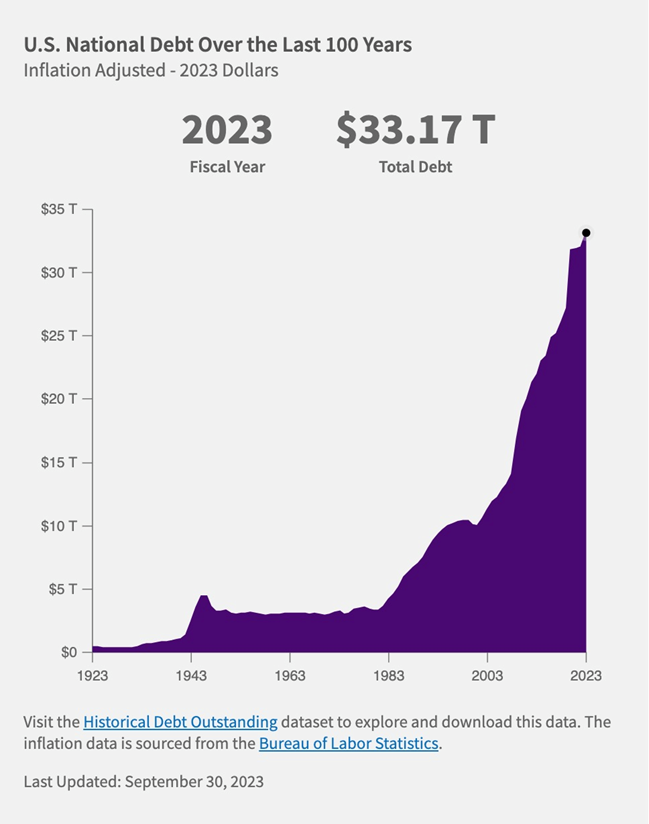

The US Treasury recently reported that, as of Dec. 29, 2023, total US debt surpassed $34 trillion for the first time. Compare this to January 2009, when the debt was just $10.6 trillion. For context, the debt rose by $1 trillion over the past three months, $2 trillion over the past six months, $4T over the past two years, and $11T over the past four years.

(Note that the national debt does not include debts carried by state and local governments, nor does it include debts carried by individuals, such as credit card debt or mortgages.)

Source: FiscalData

Source: FiscalData

Source: Zero Hedge

Source: Zero Hedge

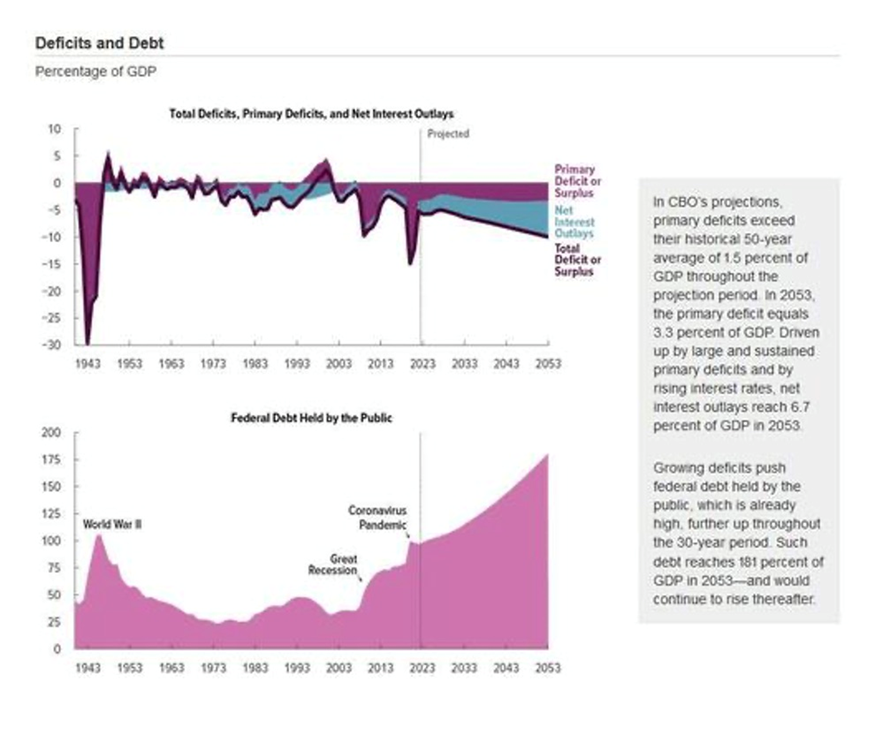

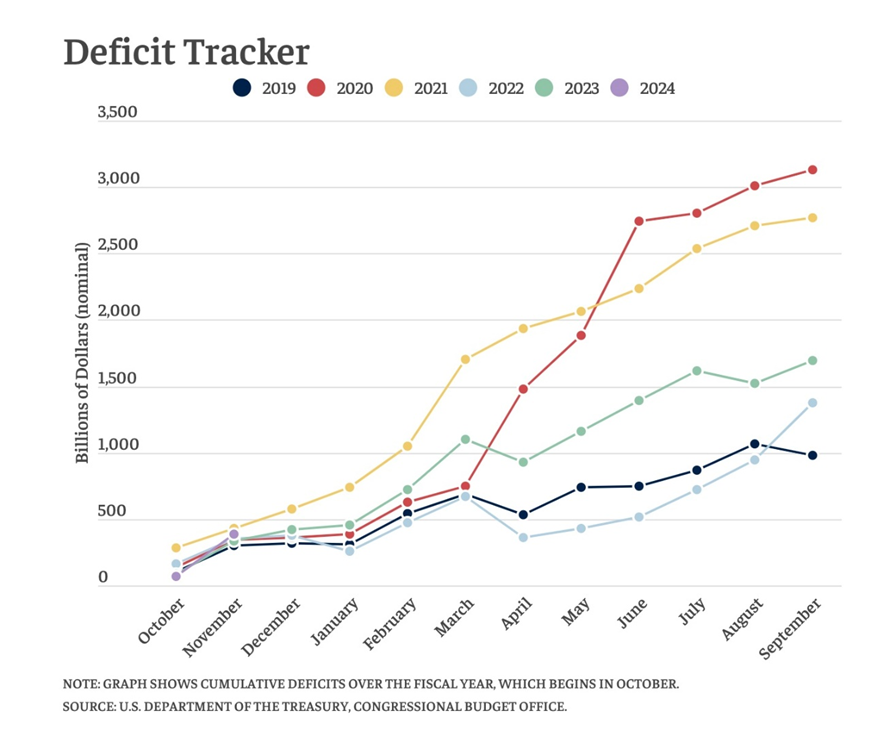

According to the Bipartisan Policy Center’s deficit tracker, even before the pandemic, the federal government ran large and growing budget deficits at nearly $1 trillion per year. Emergency spending measures to deal with the economic fallout from covid-19 pushed budget deficits to levels not seen since World War II. Although the deficit has fallen to pre-pandemic levels, deficits are projected to grow significantly over the coming decades, states the BPC.

Source: Bipartisan Policy Center

Source: Bipartisan Policy Center

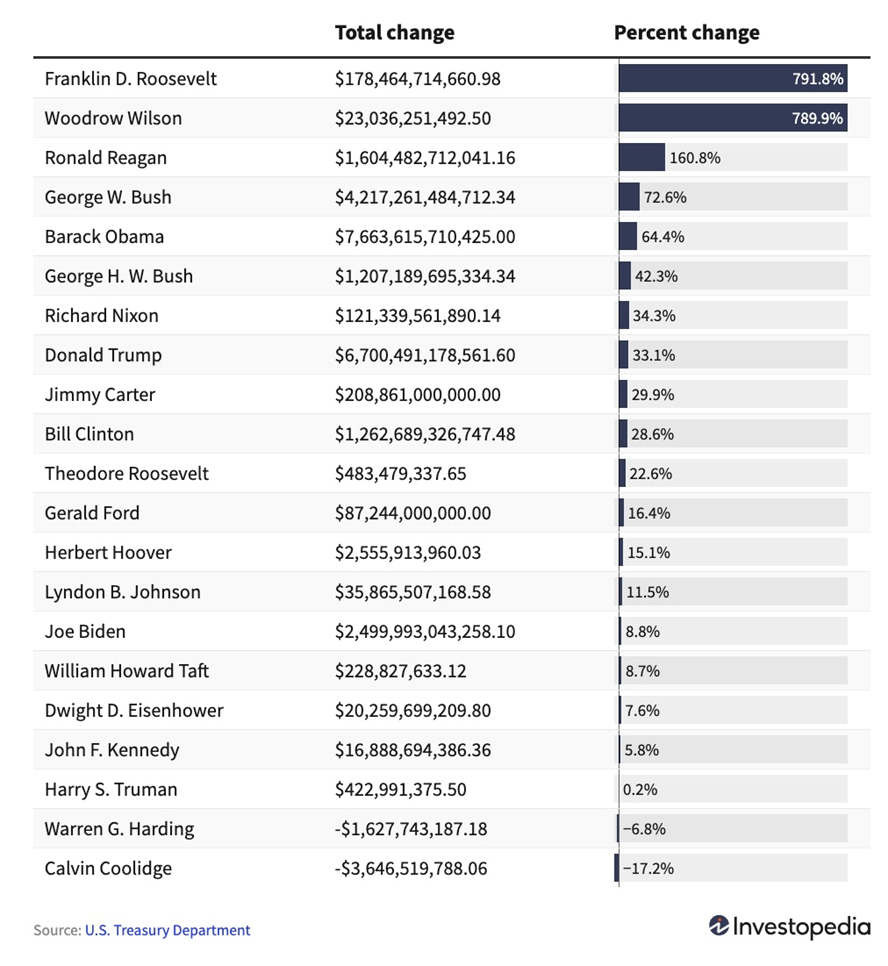

Presidents Trump and Biden have both been criticized as being especially loose with the public purse. Trump is actually eighth on Investopedia’s list of the most profligate presidents.

Debt by US President. Source: Investopedia

Debt by US President. Source: Investopedia

When history is written to include Biden, however, he is likely to be up there. Since taking office in 2021, the national debt has grown by over $6.24 trillion, largely driven by covid-19 relief measures. According to Congressional Budget Estimates, Biden’s American Rescue Plan would add $1.9T to the national debt by 2031.

Among his other big spends are: the trillion-dollar bipartisan infrastructure bill signed into law in November 2021; his amended student loan forgiveness program which could cost $230 billion over 10 years; and his Inflation Reduction Act, which focuses on green energy initiatives.

Investopedia notes the national debt increased nearly 40-fold under Abraham Lincoln (1861-65), the largest multiple in US history, while for presidents in either the 20th or 21st century, Roosevelt was the top spender.

Over the past 60 years, nearly every US president has run a record budget deficit at some point, with former Presidents Trump, Obama, and George W. Bush running the largest US budget deficits in history, states the financial news and education site.

Before 1930, almost all budget deficits run by the American government were the result of wars. The government borrowed about $211 billion to help pay for World War II. After invading Iraq and Afghanistan, and starting a War on Terror following the 9/11 attacks, the cost of these three wars in September 2021 was estimated at $8 trillion.

The ongoing cost of wars is reflected in the annual military budget, which reached a record $600 billion in 2009 as Bush’s presidency ended, Investopedia states. In December 2023, the US approved a $250 million aid package to Ukraine to help in its war with Russia. This is in addition to $75 billion (with a b) in assistance between January 2022 and October 2023.

Government relief during the Great Recession and the pandemic has also cost trillions. Obama’s 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was an $832 billion fiscal stimulus package. In 2020, following government-mandated business shutdowns and a sharp rise in unemployment, the Trump White House passed the $2.2T CARES Act, which authorized direct payments of $1,200 per adult and $500 per child for American families making less than $75,000 a year.

The following year, President Biden passed another stimulus package called the American Rescue Plan Act, worth about $1.9 trillion.

Investopedia points out it isn’t only presidents who are given the chance to run up, or constrain, the national debt. Congress must vote on appropriations and initiatives proposed by the president, and members of Congress can introduce proposals which must be voted on before they are sent to the president for signature.

Inflating away the debt?

There is a school of economic thought that says it is possible to “inflate away the debt”. This is when the government deliberately generates inflation as a way of reducing its debt burden.

Without getting too technical, the way this works is through expansionist monetary policy. The Federal Reserve can, if it wants to, create more inflation by increasing the money supply, lowering interest rates, or engaging in quantitative easing (QE). As inflation rises the nominal value of the debt stays the same but the “real” value decreases, because of inflation’s effect of eroding the currency’s purchasing power.

We already know that inflating away the debt doesn’t work. The Fed’s recent rate-hiking cycle is a case in point. For a year and a half, the Fed kept raising interest rates, but it had to stop because higher rates were damaging the US economy. Inflating away the debt causes economic destruction not only domestically but in developing economies, whose currencies are worth less than the stronger US dollar reserve currency. Now that rates are dropping, the US dollar is weakening.

A post on Seeking Alpha says inflationists make two mistakes when it comes to government: the first assumes that government debt is more important than consumer debt, and the second is that it’s not so easy to inflate away government debt.

Author Michael Shedlock also asks what would be the costs of a “successful” inflation campaign. These could include (and have included) rising mortgage rates, higher energy costs, and higher future costs of unfunded medical liabilities and social security payments, not to mention the higher interest on the national debt.

“Inflationists act as if unfunded liability costs and interest on the national debt stay constant,” Shedlock writes. “Also ignored is the loss of jobs and rising defaults that will occur while this “inflating away” takes place. Tax receipts will not rise enough to cover rising interest given a state of rampant overcapacity and global wage arbitrage.”

“Net interest costs soared to $659 billion in fiscal year 2023, which ended September 30, according to the Treasury Department. That’s up $184 billion, or 39%, from the previous year and is nearly double what it was in fiscal year 2020.” CNN

Fun facts:

Interest costs nearly doubled over the past three years, from $345 billion in 2020 to $659 billion in 2023.

Interest is now the fourth-largest government program, behind only Social Security, Medicare, and defense.

The federal government in 2023 spent more on net interest than it did all spending on children, and it also spent more on interest than most major programs or program areas including Medicaid, veterans’ programs, food and nutrition programs, and education

Interest payments over fiscal year 2024 wll be just over $1 trillion according to Blomberg.

The US Federal government net tax revenue for fiscal year 2024 is budgeted at $5.04 trillion.

How long before interest payments on the debt exceeds revenues?

Debt Jubilee

The global debt overhang has severely curtailed governments’ ability to deal with a major financial crisis such as a recession, war or pandemic.

A cross-the-board ‘Debt Jubilee’ might sound radical, but a reading of history shows that retiring debt can actually make a country’s economy, and its indebted citizenry, all the better for it.

The term ‘Jubilee’ comes from the Old Testament. The book of Deuteronomy refers to a sabbath year during which any slaves would be freed, and everyone would be allowed to return to their family farms and live off the land. During the Jubilee, all debt obligations would be forgiven — such as land or crops that debtors had pledged to creditors.

The main economic justification for a modern Debt Jubilee is simple. With debts forgiven, governments could spend the money currently devoted to interest and principal repayments on worthwhile programs; businesses would suddenly be freed from debt bondage and could expand/ hire more staff; and households would have more disposable income, all of which would, in turn, increase aggregate demand and encourage economic growth.

Canadian students leaving university owe an average $28,000; it’s not uncommon for law or medical students to carry a debt load into their first job surpassing $100,000. Student loan debt is a major inhibitor to college/ university grads being able to obtain a mortgage.

During the financial crisis, the Obama administration tried bringing in mortgage forgiveness, but was unable to get it through Congress. Ironic that in 2008, the Federal Reserve printed $4 trillion to buy up the banks’ bad debts, while Congress sat back and allowed 10 million American homeowners to be foreclosed.

An outright cancelation of sovereign debt shouldn’t be ruled out. During the Depression, France and Greece had about half of their national debts written off completely. In 1953, the London Debt Agreement between Germany and 20 creditors wrote off 46% of its pre-war debt and 52% of its post-war debt. The country only had to repay debt if it ran a trade surplus, thus encouraging Germany’s creditors to invest in its exports, which fueled its post-war boom. In 2000, $100 billion worth of debts owed by developing countries were wiped off the books.

Again, this is not as far-fetched as it sounds. Because we live in a fiat monetary system, currencies are not backed by anything physical; the reserve currency, the US dollar, was de-coupled from the gold standard in the early 1970s. It’s not like a raid on vaults full of gold, which have an inherent, physical store of value.

In reality, there is nothing preventing central bankers from doing a complete global reset, putting all debt back to zero.

The benefits of a Debt Jubilee would accrue to governments no longer bound to austerity programs; businesses that could invest in their operations instead of paying interest and principal to corporate bondholders; and taxpayers, who would benefit from increased social spending and higher household disposable income.

Of course, not everyone wins from a Debt Jubilee. The losers would include credit card companies, auto manufacturers and banks, all of which would lose the value of the debt which for them is an asset.

Conclusion

We and others have been warning about debt for quite a while.

The Fed can telegraph its intentions of cutting interest rates all it wants, the fact remains that at such unsustainably high debt levels, the interest payments will eventually cripple the federal government. Politicians are addicted to spending and the current monetary system allows it to continue without consequences, through rampant money-printing.

In 2019, before the coronavirus crisis, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) calculated that net interest payments will nearly triple over the next decade, to $928 billion by 2029. The projections are too conservative. In 2024 we’re past there, five years ahead of schedule — interest payments have surpassed $1 trillion, while the national debt has ballooned from $23.2 trillion in pre-pandemic 2019 to $34 trillion, post-corona.

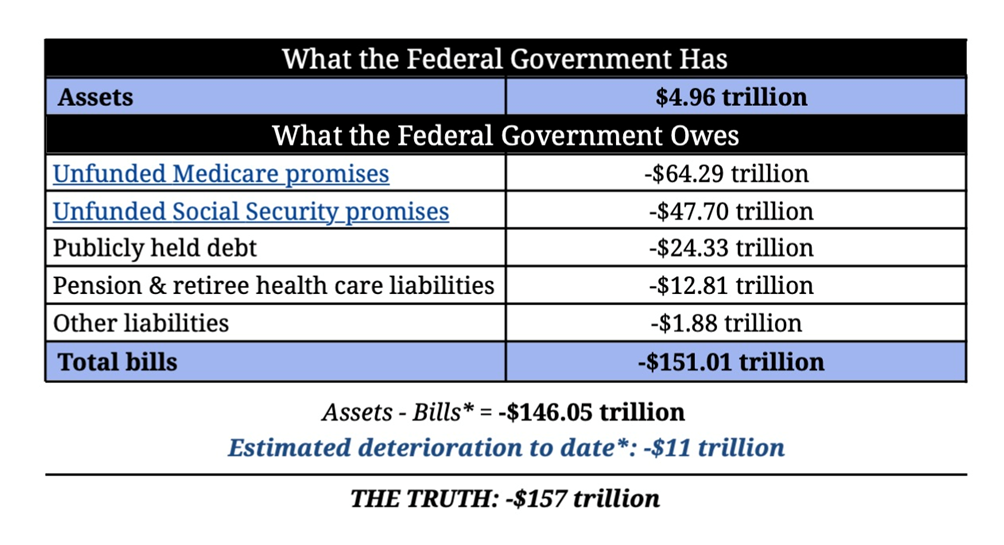

Some see the national debt going much higher, given that the way it is calculated now, doesn’t include unfunded Social Security and Medicare promises. When that $151 trillion worth of bills is added, “the truth” is closer to $164 trillion.

Source: Truth in Accounting

Source: Truth in Accounting

The people supposedly represented by the government can’t afford that level of interest (they will suffer even higher interest payments on their own debt), same as businesses cannot afford higher interest payments on their debt. Corporations will simply pass on the higher interest obligations to their customers, cut dividends or in the worst-case scenarios, lay off staff.

But there is a way to avoid this slow-moving car crash — a global debt reset — a Debt Jubilee, if you will. Imagine what could be achieved if all the central banks acted together in retiring all the world’s debt — all $307 trillion of government, corporate and consumer loans. Of course, the financial institutions would balk; their hands would need forcing. But…

A global-wide reboot effect on the economy would be immediate and profound.