Poland’s central bank, the National Bank of Poland (NBP), which stunned gold markets back in 2019 when it purchased 100 tonnes of gold bars in London and then promptly flew the gold back to Warsaw, has just confirmed that it now plans to buy another 100 tonnes of gold during 2022.

The news was confirmed this week by Adam Glapiński, president of Poland’s central bank, in a 5 October special interview with Polish magazine ‘Strefa Biznesu’ in advance of the ‘Congress 590’ economic conference in Warsaw. As well as heading the Polish central bank, Glapiński is also an economics professor.

While Poland currently holds 230 tonnes of monetary gold reserves and sits in 24th place in the world sovereign gold holdings table, the planned addition of 100 tonnes of gold during 2022 would boost the country’s gold reserves to 330 tonnes and catapult Poland up to 18th place in the rankings, ahead of major gold holders such as the UK, Saudi Arabia, Austria, Spain and Thailand.

Glapiński’s interview with the ‘Strefa Biznesu’ magazine was conducted by journalist Zbigniew Biskupski, and the interview is even titled by the Polish central bank (NBP) as “Another 100 tons of gold in 2022". See NBP website here.

Adam Glapiński, president of Poland’s central bank, the National Bank of Poland

Adam Glapiński, president of Poland’s central bank, the National Bank of Poland

The Investment Benefits of Gold

Given that Glapiński’s 5 October interview covers substantial ground about Poland’s gold reserves, the relevant sections are worth highlighting here, translated of course from the original Polish into English.

Zbigniew Biskupski (Interviewer):

“The National Bank of Poland has accumulated a record amount of nearly 230 tons of gold. What is the purpose of the aggregation of such assets by the central bank?”

Adam Glapiński (NBP President):

“First, a short answer, but I hope it appeals to the imagination. Why does the central bank own gold?

Because gold will retain its value even when someone cuts off the power to the global financial system, destroying traditional assets based on electronic accounting records. Of course, we don’t assume that this will happen. But as the saying goes – forewarned is forearmed.

And the central bank is required to be prepared for even the most unfavorable conditions. That is why we see a special place for gold in our foreign exchange management process.

After all, gold is free from credit risk and cannot be devalued by any country’s economic policy. Besides, it is extremely durable, virtually indestructible. Let me give you an example. During the inspection of the NBP gold reserves at the Bank of England, our employees could admire a gold stock from a ship torpedoed during the First World War. The bar, except for minor deformations, was practically intact!

Due to the above factors, gold is treated as the so-called a safe-haven asset, which means that its price usually increases in conditions of increased risk, financial and political crises or other turmoil in the global markets.

As a result, gold fits very well with the basic objectives of maintaining foreign exchange reserves, which include securing the country’s payment liquidity, even in extremely unfavorable conditions, strengthening Poland’s credibility on financial markets, and reducing the risk of a sudden outflow of capital.

Additionally, gold is characterized by a relatively low correlation with the main asset classes – especially the US dollar dominating the NBP reserve portfolio – which means that including gold in the reserves reduces the financial risk in the investment process.

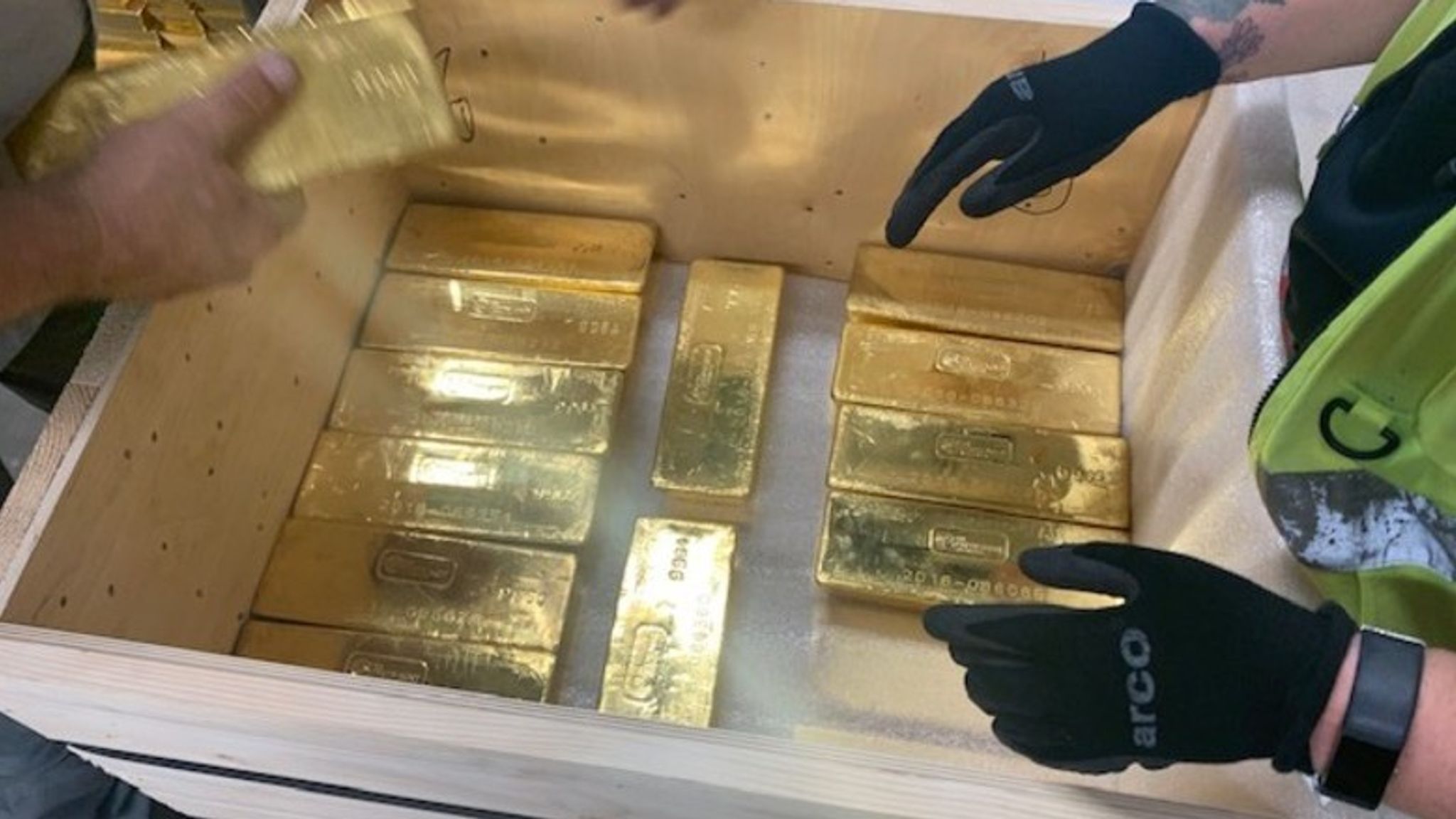

Gold bars in the vaults of the Polish central bank. Source

Gold bars in the vaults of the Polish central bank. Source

100 tonnes purchase in 2022

Interviewer:

“Does this mean that if you are able to continue your mission at the National Bank of Poland as part of your second term in office as the President of the NBP, we can expect more gold purchases?”

Adam Glapiński:

“Yes, in order to further increase Poland’s financial security, we will continue the current policy, we will certainly strive to increase our gold resources. However, the scale and pace of purchases will depend, among others on the dynamics of changes in official reserve assets and current market conditions. I initially assume that I will propose to buy another 100 tons in 2022.”

For those thinking ‘didn’t the Polish central bank earlier this year already mention buying 100 tonnes of gold?’, you would be correct. Back in March 2021, Adam Glapinski in an interview with Polish magazine Sieci said that Poland planned to buy 100 tonnes of gold over the coming years:

“Over the course of a few years we want to buy at least another 100 tonnes of gold and keep it in Poland as well,” he said.

However, what has changed is that this gold buying timeline has now been compressed from a few years into 1 year, and the NBP will now execute the plan in 2022, with the NBP’s operating strategy being guided by the rule of thumb – as official reserve assets of the Polish central bank grow over time, it will continue to buy more and more gold using a target percentage of gold to total reserve assets.

Later in the 5 October interview, while talking about central bank reserve diversification, Glapiński added that gold forms a key part of this diversification strategy:

“Taking all this into account, in 2020 the NBP Management Board adopted a new reserve management strategy.

One of its pillars is the further diversification of the currency structure of provisions, which should limit the impact of the exchange rate risk on our financial result.

In addition, we are gradually and prudently expanding the range of financial instruments used. We have been investing in the USD corporate bond market for almost a decade, and this year we also took a modest exposure to the equity market.

Besides, of course – we believe in the diversification potential and long-term profitability of gold, the resources of which we plan to expand further.”

NBP president with a Good Delivery gold bar in the vaults of Poland’s central bank

NBP president with a Good Delivery gold bar in the vaults of Poland’s central bank

Glapiński the Goldbug

A week prior to his 5 October interview, the Polish central bank president was again talking about gold, this time on 27 September in a gold specific question and answer session for readers of the Polish news and political magazine ‘Do Rzeczy’, which was titled “Everything you want to know about gold. NBP President especially for DoRzeczy.pl readers!”.

Imagine the US Treasury’s Janet Yellen or the US Federal Reserve’s Jay Powell holding a “Everything you want to know about gold” Q&A. It would never happen.

In contrast to Yellen-Powell, the Polish central bank president in his 27 September Q&A was quite transparent and open, beginning by highlighting that the NBPs purchase of 125.7 tonnes of gold over 2018-2019 (25.7 tonnes in 2018 and 100 tonnes in 2019) and the 100 tonnes repatriation in 2019, had sparked huge interest across Poland:

“Since we announced that in 2018-2019, the National Bank of Poland purchased a total of 125.7 tons of gold, and then decided to transfer nearly half of the resources (100 tons) from the Bank of England to the NBP vaults, interest in these activities and their motives continues.

The NBP, and sometimes me personally as the President of the Central Bank, receive numerous inquiries – from journalists, parliamentarians and Poles – about the reasons for the decision, their conditions and consequences.

Of course, we treat each such question seriously and provide appropriate explanations, but over time we noticed that many questions concern similar issues. Therefore, it is worth shedding light on the NBP gold resources, shrouded in an aura of mystery, and opening the armored doors of our vaults to a wider group of people. Welcome!”

There then followed questions, the first of which was: “How much gold does the NBP actually have and how does it compare to other central banks?

Glapiński: “As at the end of August 2021, the NBP gold stock amounted to 7.402 million ounces, i.e. 230.2 tons. The size of the gold stock held by NBP is essentially shaped by strategic purchases of gold for reserves, most recently made in 2018–2019.

… the monthly data on the NBP gold reserves may change slightly… such changes (increases / decreases in the gold stock) usually in the order of several hundred or tens of thousands of ounces (i.e. not more than a few tons), are related to the implementation of the investment process and do not reflect strategic decisions regarding the management of NBP gold reserves.”

Some of the 100 tonnes of NBP gold which was airlifted from London to Warsaw in 2019

Some of the 100 tonnes of NBP gold which was airlifted from London to Warsaw in 2019

Don’t count your chickens – The Polish Gold in London

Question 2: “Where is Polish gold stored? Why do we store some of the resources abroad?"

Glapiński: “Nearly half of the gold holdings – 104.9 tonnes – are kept in the vaults of the National Bank of Poland, while the remaining 125.4 tonnes are kept in accounts abroad, mainly in the so-called allocated account at the Bank of England, in London.

It’s worth noting that the Bank of England not only offers gold bar storage services, but also organizes the market for its trading – apart from the National Bank of Poland, accounts are also run by the majority of entities active on the gold market, thanks to which our resources can be actively invested, e.g. under the so-called placement transactions.

For investment purposes, the NBP also uses gold accounts kept by other correspondents, but the balances kept on these accounts constitute a very small percentage of gold reserves. Such a diversity of gold storage locations not only fits well with the practice of central banks, but also allows for flexible management of gold resources and at the same time reduces the costs of keeping the gold."

Here Glapiński confirms that the NBP is actively engaged in lending out it’s gold in London to LBMA bullion banks, in what he calls placement transactions, but which are otherwise known as ‘gold deposits’ and ‘gold loans’. When the NBP purchased 100 tonnes of gold in London in 2019 and then also repatriated only 100 tonnes of gold from London to Warsaw, even though it claimed to hold a total of 228.6 tonnes of gold at the Bank of England, the question arose as to why the NBP did not at that time repatriate the entire 228.6 tonnes.

In July 2019, in the article “Poland joins Hungary with Huge Gold Purchase and Repatriation“, I posed the question:

“Having bought 100 tonnes of gold at the Bank of England this year, and now wanting to repatriate 100 tonnes, the question then arises, are the recent purchases of 100 tonnes the only gold the Polish central bank really has access to in London, with the rest in some way encumbered and unavailable?"

We now have evidence that the NBP gold that is still stored in London is being activated in these very gold transactions (gold loans and placements), a fact which was obvious, but which mainstream media reporters rarely acknowledge. With about 105 tonnes of the Polish gold now held in Poland, that still leaves about 125 tonnes that is still at the Bank of England, or is it?

While the NBP is more transparent than most about it’s gold reserve holdings, this 125 tonnes ‘held in London’ is still shrouded in secrecy. As I wrote in the November 2019 article “Polish central bank airlifts 8000 gold bars (100 tonnes) from London to Warsaw”, when the NBP claimed to hold 123 tonnes of gold in London:

“If the Poles are serious that their central bank “build the economic strength of the Polish state" and “create reserves that will safeguard its financial security", they should .., find out where exactly is this 123 tonnes of gold that is supposedly at the Bank of England. For something in all of this doesn’t smell right.

Some enterprising Poles may therefore want to ask the NBP to undertake a full physical audit of this 123 tonnes of gold, publish a full audit report, publish a full weight list of the gold bars in London (with refiner serial numbers), and publish a full disclosure of whether and how much of this 123 tonnes of gold is held in allocated form and how much is lent, loaned, pledged, or encumbered in any shape or form….but something tells me the central banks in question will not want to cooperate."

8392 Good Delivery Gold Bars in Warsaw

Going back to 27 September Q&A, the questions continue:

Question 3: In what form is the NBP gold that is held in central bank vaults?

Glapiński: “The NBP vaults contain 104.9 tons of gold, which corresponds to 3.371 million ounces… in the form of bars: there are currently 8,392 of these bars in the NBP vaults in Poland. All our bars – not only those in the NBP vaults, but also those kept at the Bank England – meet the highest purity standards known as ‘London Good Delivery’”.

Question 3: Is the gold in the NBP vaults part of the pre-war resources of the Bank of Poland?

“No. The oldest bars included in today’s resource in the NBP treasury found their way to the central bank relatively late, only in the 1980s and early 1990s – in total there were 392 pieces with a total weight of approx. 4.9 tons.

For the next 25 years, this state did not change, and only after the transfer of 100 tons of gold from the vaults of the Bank of England to Poland in 2019, another 8,000 gold bars appeared in the vaults of the National Bank of Poland.

Glapiński completed his 27 September Q&A with a wrap-up saying that:

“Gold is the “most reserve" of our reserve assets: it diversifies geopolitical risk and is a kind of anchor of confidence, especially in times of tensions and crises.”

Some of the NBP’s wholesale ‘400 oz’ gold bars that were repatriated to Poland in 2019

Some of the NBP’s wholesale ‘400 oz’ gold bars that were repatriated to Poland in 2019

The Golden Pillar

Given Glapiński’s enthusiasm for central bank investment into gold, you might at this stage guess that the NBP president talks about gold more frequently than central bank governors of other nations, and that would indeed be correct. For not only has Glapiński been doing interviews about gold in the Polish press this year, he even wrote an article explaining his gold investment thesis.

Written in July 2021 for the publication Capital Finance International (CFI.co) and published on the CFI.co website here, as well as on the NBP website here, Glapiński’s article, which is less than 3 pages long, is titled “Investing for the long-term: gold as a pillar of NBP’s reserve management strategy“.

In his paper, Glapiński explains that FX reserves (including gold) are held primarily to “enhance the country’s financial credibility" which impacts costs of international financing, the stability of the Polish currency (the zloty), and the stability of capital flows. Glapiński writes:

“At the end of May 2021 official reserve assets of Narodowy Bank Polski accounted for USD 162.7 billion, increasing in USD terms roughly six-fold from USD 27.5 billion in 2000 and almost doubling over the past decade.“

“The underlying idea is simple: if the FX reserves are not deployed to combat some financial stability or balance-of-payments emergency, they are to be preserved, preferably increased and passed on to another generation.

With such a strict investment mandate, it is perhaps no wonder that NBP considers gold as a special component of its official reserve assets. After all, the characteristics of gold are very well aligned with the precautionary role of maintaining foreign reserves and preserving capital in the long term, weathering periods of stress and varied market conditions.“

The NBP head then waxes lyrical on the benefits of physical gold, looking like he might even have read the BullionStar 101 gold primer, as he continues:

“Gold offers some unique investment features – it is devoid of credit risk, it is not easily “debased” by monetary or fiscal mismanagement of any country, and while its overall supply is scarce its physical features ensure durability and almost indestructibility. For all these reasons gold is considered as an ultimate strategic hedge.

The practical side of it all is that gold acts like a safe haven asset, in that its value usually grows in circumstances of increased risk of financial or political crises or turbulences. In other words, the price of gold tends to be high precisely at times when the central bank might need its ammunition most."

On the subject of activating gold that is still stored at the Bank of England in London, Glapiński writes:

“the storage of gold in London creates for NBP an opportunity to increase the profitability of the official reserves by placing gold deposits on the interbank market.“

Again, what Glapiński means here is the Polish central bank lends out gold that it held at the Bank of England to LBMA bullion banks in return for a fee. This gold is then considered to be a ‘gold deposit’, with control of the gold passing to the bullion bank, even though the central bank still accounts for the lent gold as being on it’s balance sheet.

Good Delivery gold bar arrangement in the vaults of the Polish central bank. Source

Good Delivery gold bar arrangement in the vaults of the Polish central bank. Source

Conclusion

Given the NBP president’s attunement to the value of holding physical gold, and his frequent media appearances advocating gold’s benefits, it should no longer be surprising, if it ever was, that Poland’s central bank is leading the charge into accumulating huge quantities of monetary gold reserves. For while some central bankers go out of their way never to mention the yellow metal, Poland’s central bank head is quite the opposite.

Wrapping up his July article, Glapiński even quotes Shakespeare but decides not to take his advice, at least on the subject of the NBP reserves:

“Shakespeare was right and generally in life “all that glitters is not gold… gilded tombs do worms enfold”. But, while managing NBP’s foreign exchange reserves, we have a somewhat narrower philosophical focus and certainly don’t mind some glitter in our portfolio.“

In Polish, Poland’s national currency the ‘złoty’ literally means ‘golden’, and is historically derived from the use of that term which referred to gold coins in circulation in 14th and 15th century Poland. A fact which Glapiński no doubt finds appropriate as he steers the Polish central bank towards it’s next 100 tonnes gold purchase over the course of 2022.