For years we’ve been reporting on how a decline in productivity from existing copper mines, driven by open-pit to underground expansions, a decline in ore quality, and resource nationalism, has been combining with a lack of new discoveries caused by a shortage of investment in exploration, to produce a shortfall of mined copper.

Consider: out of 224 copper deposits found between 1990 and 2019, only 16 have been discovered in the last decade.

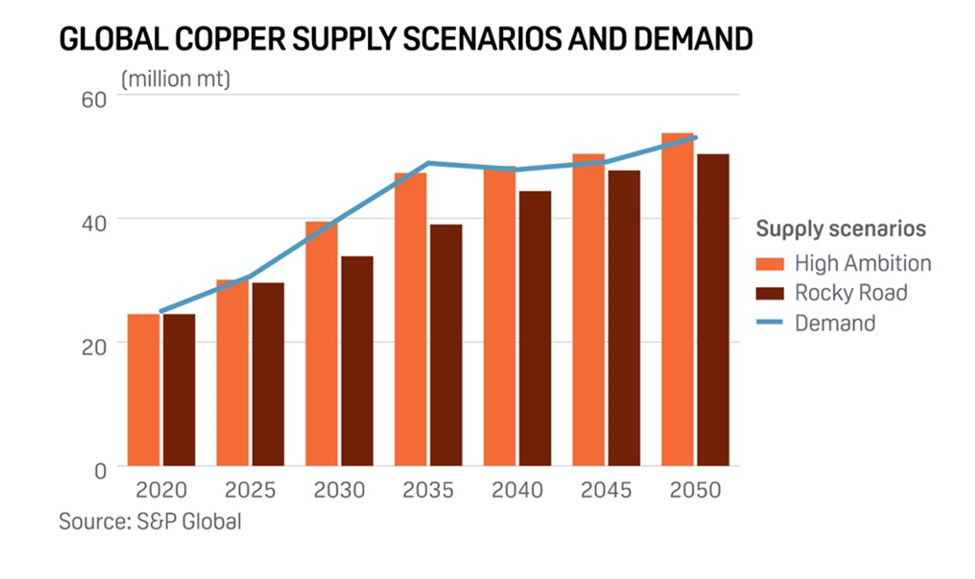

According to McKinsey, a consulting firm, the electrification trend is expected to increase annual copper demand to 36.6 million tonnes by 2031, with supply forecast to be around 30.1Mt (from the current 22Mt), creating a 6.5Mt deficit at the start of the next decade.

Some of the world’s largest mining companies and metal traders are warning the shortfall could arrive as early as 2025.

The International Copper Study Group (ICSG) says the copper market is facing another year of deficits. The group’s April forecast, via Reuters, calls for a supply shortfall of 114,000 tonnes in 2023, compared to a 431,000-tonne deficit in 2022.

When ICSG last met in October, it was expecting global mine production to grow by 3.9% in 2022 and 5.3% this year. It now thinks growth was 3% last year, and revised its forecast down to 3% in 2023.

The Reuters story says the expected wave of new supply from four new mines — the DRC’s Kamoa-Kakula, Quellaveco in Peru, along with Quebrada Blanca II and Spence-SGO in Chile – is being offset by multiple hits to existing operations:

The ICSG cites as reason for its lowered mine growth expectations “operational and geotechnical issues, equipment failure, adverse weather, landslides, revised company guidance in a few countries and community actions in Peru”.

Copper price rallies

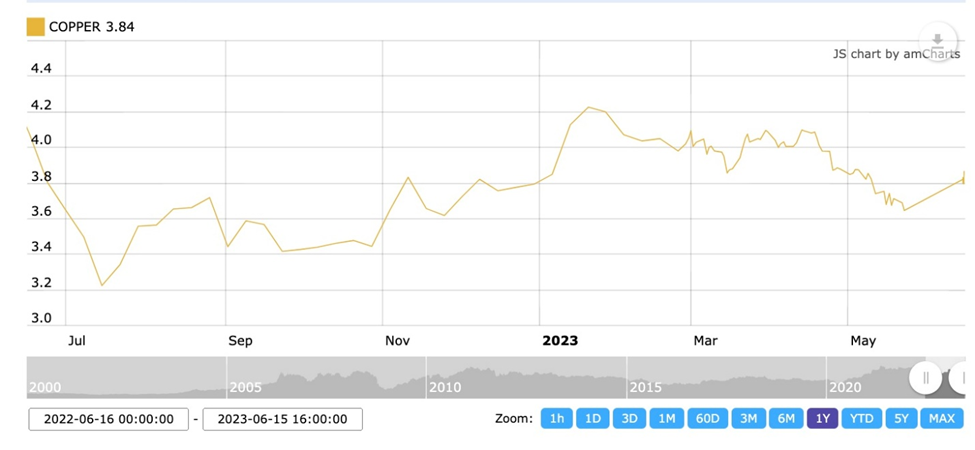

As of this writing, the spot price was trading at $3.84 a pound, a far cry from its record-high $4.80/lb reached in early March, 2022.

Source: Kitco

Source: Kitco

Headwinds include a slower than expected rate of economic recovery in China, and concerns that the United States could end up in recession after

10 straight rate hikes by the Federal Reserve, done to contain inflation.

Yet some of the industry’s most prominent influencers say that copper’s current pullback is temporary, and that its upward trajectory is likely to resume. Robert Friedland, the billionaire founder of Ivanhoe Mines, said despite copper falling below $8,000 a ton for the first time in six months, on May 24, the metal that is essential for the decarbonization of the global economy continues to face a supply crisis.

“It’s momentary,” Friedland said in a Bloomberg TV interview at the Qatar

Economic Forum. “We’re very very bullish on demand.”

A ray of hope for copper and other metals shone on Wednesday, June 14, when the Fed decided at its regular meeting to pause interest rates — the first time it has done so since embarking on a rate hike cycle in 2022.

While copper actually declined on the news, earlier this week the red metal rallied sharply after the People’s Bank of China cut a short-term interest rate to boost economic growth. Investing.com reported Markets now expect the PBOC to enact more rate cuts as it moves to spruce up a slowing economic rebound in China. More stimulus in the country is expected to drive up economic activity and fuel copper demand later this year.

Shanghai copper prices rose Wednesday to a seven-week high, with the most-traded July copper contract on the Shanghai Futures Exchange up 1.4% to $9,478.49 per tonne, its highest since April 25.

ICE sales set to peak in 2025

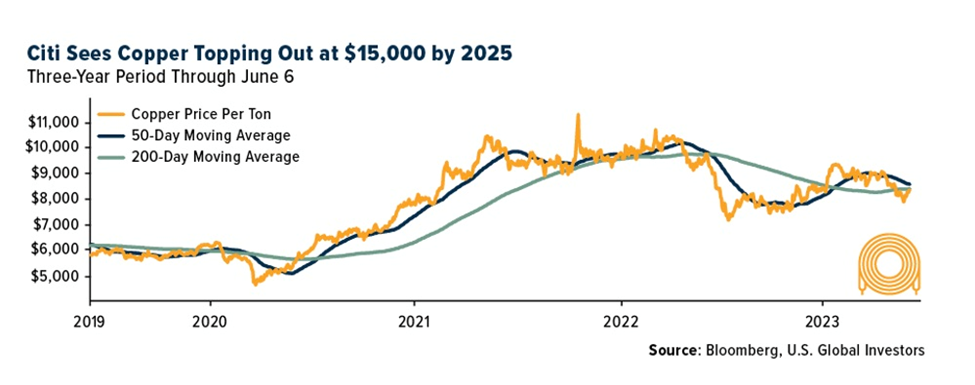

In fact the copper market could see an “unprecedented inflow” in coming years as investors seek to profit from the metal’s anticipated surge in value, driven by growing demand for electric vehicles (EVs) and renewable energy, according to Citigroup, via U.S. Global Investors.

Max Layton, Citgroup’s managing director of commodities research, said in an interview with Bloomberg that now is an ideal time for investors to buy, with the price still muted due to recession concerns. He thinks copper could reach $15,000 a ton by 2025, a jump that would “make oil’s 2008 bull run look like child’s play.”

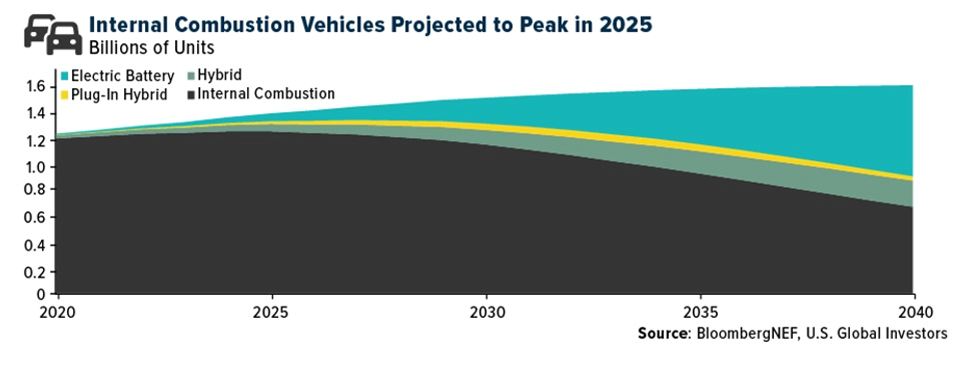

As Robert Friedland alluded to earlier, much of copper’s bullish fundamentals rest on the demand side. Electric vehicles require triple the amount of copper as regular cars and trucks, and then there’s all the copper needed for EV charging stations, renewable energy, and new transmission lines.

While there are obstacles to EV penetration, such as sticker shock and range anxiety, EV sales are rising. Last year they reached 10.5 million, and according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, they could reach 27 million by 2026. In fact Bloomberg predicts the global fleet of ICE vehicles will peak in as little as two years, after which the market will be dominated by EVs and hybrids.

Looming shortage

It is estimated that more than 20 million tonnes of copper are consumed each year across a variety of industries, including building construction, power generation/ transmission and electronic product manufacturing.

In recent years, the global transition towards clean energy has stretched the need for copper even further, as a lot more of the metal will be required to feed our renewable energy infrastructure such as photovoltaic cells used for solar power and wind turbines.

BloombergNEF estimates that copper demand, driven by various clean energy initiatives, will grow 53% to 39 million tonnes by 2040. Analysts at S&P Global are expecting an even quicker and bigger jump, with copper demand set to double to 50Mt by 2035.

As mentioned, consulting firm McKinsey expects electrification to create a 6.5-million-ton shortfall at the start of the next decade, highlighting a substantial output gap that the mining industry has to address.

The problem identified by Reuters metals columnist Andy Home, is that there is precious little copper supply in the pipeline beyond the four mines currently being brought online. (We identified them previously as the DRC’s Kamoa-Kakula, Quellaveco in Peru, along with Quebrada Blanca II and Spence-SGO in Chile.)

His December, 2022 article quotes Glencore’s CEO Gary Nagle saying, “Whatever was planned to be built has been built. There is nothing coming behind [the projects now ramping up into production].”

Glencore’s outlook on copper supply is way more pessimistic than, say, McKinsey’s. The firm says if the world is going to meet its zero emissions targets, it will be short 50 million tonnes of copper by 2030.

Clearly, the world needs new copper mines, but they can’t be built and commissioned that fast. In North America, 20 years can elapse between initial discovery and first production. We’ve got less than seven years.

Sam Crittenden, an analyst with RBC Dominion Securities, recently estimated that the energy transition’s copper requirements will mean an additional 1% of copper supply, the equivalent of one large copper mine coming online every year.

Mentioned by The Globe and Mail’s market strategist Scott Barlow in his daily roundup of research and analysis, Crittenden writes,

“It’s always been a supply story with an aging supply base, declining grades and quality projects becoming more scarce and harder to build for ESG reasons…

“We forecast copper prices of $4.50/lb from 2025-2027 for this reason which could be conservative if supply struggles to respond… Quality shovel ready projects are scarce and getting more difficult to build: When we look at the list of available copper projects it’s notable that there is a lot of copper out there but a lot of it may never come out of the ground.”

Chile problems

Chile serves as a good example of why new copper supply is so hard to come by.

The country’s output has stagnated due to deteriorating ore quality and water restrictions in the arid north. Permitting is also getting tougher.

In 2021, leftist Gabriel Boric was elected president of Chile, on a mandate to impose higher taxes, sending a chill through the mining industry which argued the change would impede competitiveness.

Constitutional reform was also on the agenda. Since then, cooler heads have prevailed. A proposed new constitution was rejected by voters last September, while an ambitious tax overhaul plan was voted down by Congress in March.

A government plan for new royalties on mining, currently moving through Congress, has been tempered to 46%.

Large mining companies have been watching these developments closely. BHP, majority owner of the world’s biggest copper mine, Escondida, wants the Chilean government to make further concessions on the tax legislation before investing an estimated $10 billion in the country. A BHP executive says Chile’s major competitors have a tax burden of 41 to 43%.

Canada’s Lundin Mining and US copper giant Freeport McMoRan, meanwhile, have been vocal about their concerns in Chile. The latter has said it will pause expansion plans, citing political uncertainty.

Lundin is more confident, agreeing last month to pay $950 million for 51% of Chile’s Caserones copper mine. The company is considering raising its stake to 70% mine for an additional $350 million. The addition of Caserones would boost Lundin’s copper output by 50%, adding to the Candaleria mine it already operates, 160 km away.

Reuters notes that Lundin’s purchase from JX Nippon Mining & Metals comes at a time when companies are seeing longer delays for permits as opposition has risen from local communities. Some projects have been rejected by the state or by courts on environmental impact concerns.

Teck has submitted for environmental approval this year, a $3 billion project to increase capacity at its Quebrada Blanca 2 mine.

In a recent note, via Bloomberg, Fitch Ratings said Chilean companies are expected to temper their growth plans this year as the likelihood of higher taxes and labor costs dim returns on new projects.

The most obvious example is Codelco. The state-owned copper miner, and world’s largest copper producer, in 2022 cut its production outlook, blaming lower recovery levels at some of its mines and ore grades at its Chuquicamata mine. The company in November said it expected 2022 output of between 1.49 and 1.51 million tonnes, compared to its previous forecast of 1.61Mt.

This week, Codelco’s CEO Andre Sougarret stepped down after less than a year in the role, as the copper miner grapples with lower production and a new role in the lithium industry. Despite investing about $3.5 billion a year to revamp its existing mines, Codelco’s copper production has fallen this year more than 11% to a 25-year low, Mining.com reported.

Desalination

Last year, Chile experienced the 13th year of a historic drought, leading Santiago to roll out unprecedented water rationing among residents. Miners are also feeling the effects. A 2022 Reuters article states that Anglo American’s flagship Los Bronces mine in central Chile saw production fall 17% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2022, partly due to water scarcity.

Mining companies are being pressured by the government, which has toughened environmental regulations, to reduce their freshwater withdrawal, and many are turning to unconventional methods like desalination.

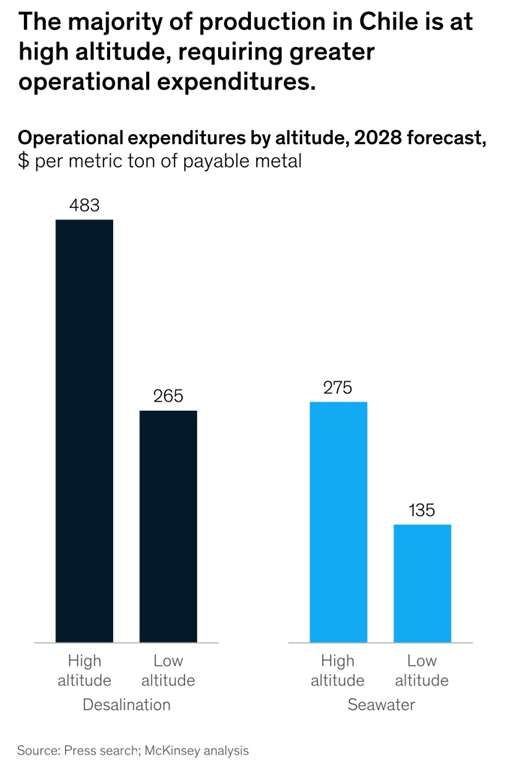

Mines such as Los Bronces, located high in the Andes, face the most challenging water problems, given that the drought is likely to continue, and there are serious engineering challenges, and costs, involved in building desalination plants close to the ocean, constructing pipelines to transport the water hundreds of kilometers inland, and pumping it to high elevations.

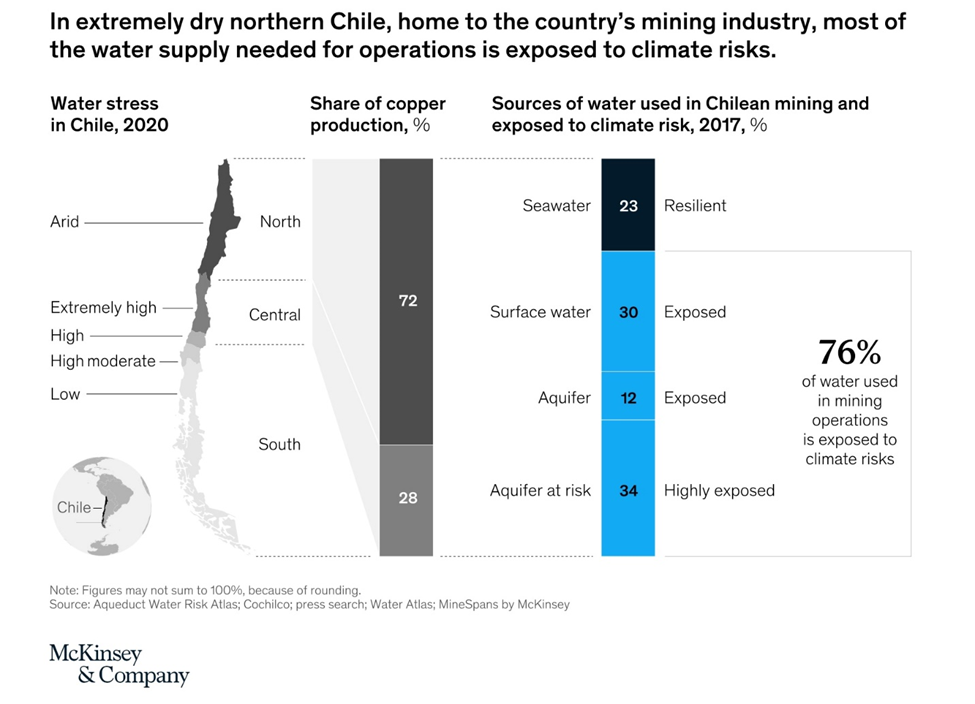

Yet according to Cochilco, mining’s use of seawater, either directly or desalinated, will increase 167% by 2032, while freshwater use will decline 45%. By then, 68% of water used by the industry will come from the ocean.

How did Chile, a mountainous country with plenty of lakes and rivers, resort to such a complicated process of getting water to its mines?

Let’s start with the fact that the mining of copper is complex and requires substantial amounts of water. Water is used at various steps to concentrate copper ores, including comminution, flotation, classification and thickening. About 90 cubic meters of water is needed to produce one ton of copper.

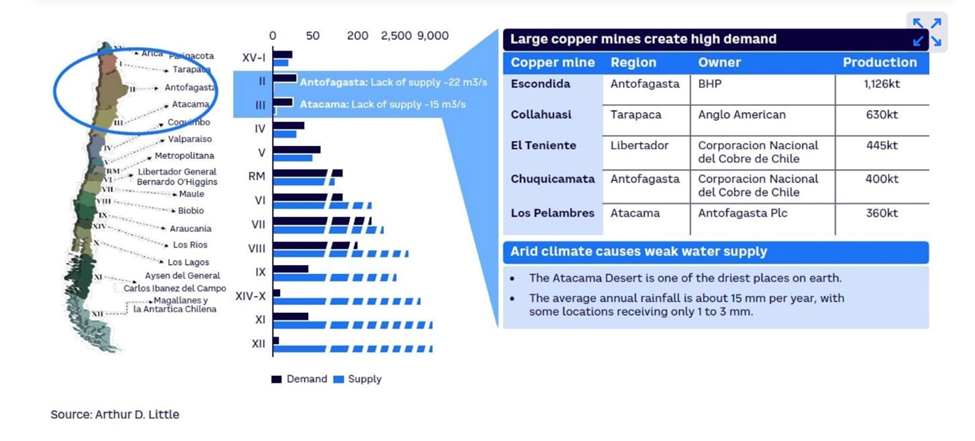

But most of the country’s copper (and lithium) reserves are located in three arid northern regions: Antofagasta, Atacama and Tarapaca. These regions are situated between two high mountain ranges, that prevent precipitation from reaching them from the surrounding Pacific or Atlantic oceans. Existing groundwater sources are insufficient to meet the demands of agriculture and the local population. The water for mining operations in these regions must therefore be desalinated on the coast and pumped across long distances and over great heights. (‘Water supply for mining industry: the Chile case’ by Arthur D. Little)

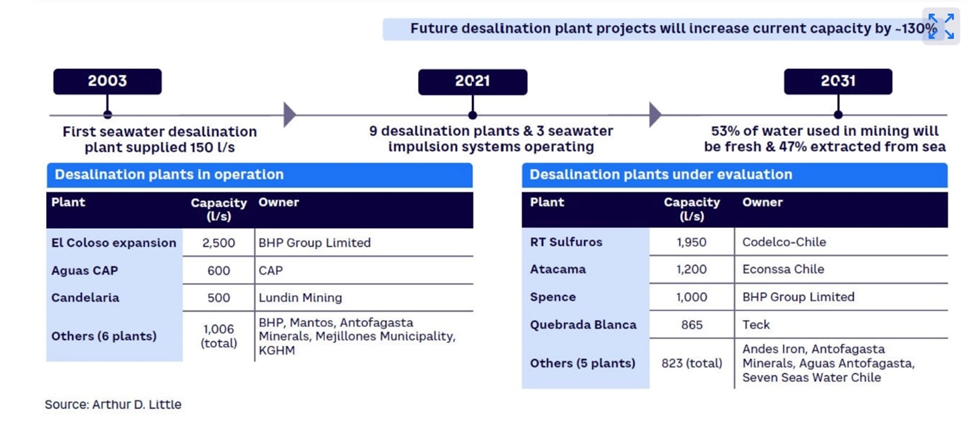

The country’s first desalination plant was commissioned in 2006 by BHP Billiton at its Escondida copper mine. By 2021, nine plants and three seawater impulsion systems were operational. Another 15 desalination projects are expected to be build before 2031. They include Antofagasta’s $2.2 billion expansion of Los Pelambres, its flagship mine, involving a desalination plant and 150-km-long water pipeline; Coldelco’s Northern District desalination plan in Antofagasta; Teck Resources’ Quebrada Blanca Hipogenos project in Tarapaca, and the Santo Domingo project by Capstone Mining in Atacama.

According to the Arthur D. Little report,

[BHP’s] system brings seawater into the desalination plant, uses a reverse osmosis process to filter out the dissolved mineral and biological residue, and circulates extracted brine and other substances back into the ocean. The resulting desalinated water is then pumped into the mine through two pipelines, both 42 inches in diameter, which are located 3,200 meters above sea level. Four high-pressure pumping stations, a reservoir at the mine, and high-voltage electricity infrastructure are needed to operate the system.

Fresh water supply and demand across Chile’s regions

Fresh water supply and demand across Chile’s regions

Timeline of increased desalination capacity

Timeline of increased desalination capacity

Along with the drought in Chile, the other factor driving more desalination is the challenge of dealing with lower-grade ores, which require more water to produce the equivalent product as higher-grade ores.

According to McKinsey, the mining industry in Chile annually consumes enough water to provide for 75% of Chile’s population.

McKinsey quotes a MineSpans analysis that found run-of-mine volumes from copper mining in Chile are expected to increase by 36% in the next decade:

Processing this lower-grade material will drive an increase in water consumption. Water-usage intensity is therefore expected to be a key factor in determining future profitability of the mining sector, especially in arid areas.

Source: McKinsey & Company

Source: McKinsey & Company

Source: McKinsey & Company

Source: McKinsey & Company

Of course, the increased water consumption will also come with other associated costs. McKinsey notes that, despite improvements in desalination technology, such as the use of membranes instead of thermal plants, increasing desalinated water capacity will trigger a large growth in energy demand for the plants and pumping stations, as well as significant brine discharge back to the sea.

Arguably there is another cost of increased desalination, one that has not been factored in by consultants, and that is pushback from local populations who like the mining companies, are water-stressed.

It’s not as if nobody else lives in the northern half of Chile and miners are free to take all the water. Indigenous populations are also competing for water rights and dealing with contaminated water supplies, the same as First Nations communities in northern BC and Alberta that have found their drinking water poisoned by oilsands and fracking operations.

A little-known fact: in Chile, water resources are private. The 1981 Water Code “enshrines free market water economics to facilitate resource use and secure property rights under competitive conditions,” reads a 2016 article in The Conversation. “In practice, the code has failed to coordinate water use and resolve river basin conflicts, and has only increased private speculation, hoarding and the monopoly over water rights.”

Forcing water users to pay a fee for unused water to avoid speculation has not protected the water rights of indigenous communities, The Conversation states. It cites the case of the Atacameno people, who lost a large amount of water to mining companies because they weren’t made aware of the need to officially register their water rights.

Consider: all the big mining firms in Chile are either investing in desalination or are planning to. There simply isn’t enough fresh water to go around.

Think about every dry village along each of these pipelines’ routes. It didn’t take much for Chileans to riot over an increase in bus fares. What’s going to happen when thirsty people who have no water for drinking, sanitation or irrigation have pipeline so close and so full of water?

Conclusion

Extracting copper seems like a fairly straightforward mining operation: blast the ore, crush it, float it, classify it and thicken it. Yet copper mining requires a lot of water, around 90 cubic meters to produce just one ton of copper.

The experience of Chile, the country producing the most amount of copper, shows that there are serious challenges in maintaining the profitability of existing operations, let alone expansions or new mines.

Chile’s mines are not only “high and dry”, requiring expensive desalination plants with pipelines running hundreds of kilometers inland and uphill, most of them are seeing lower grades, requiring more water to produce the same amount of copper that was previously mined at higher grades. In other words, the economics are becoming challenging.

Years of these problems have begun to take their toll. Just look at Codelco. Despite investing about $3.5 billion a year to revamp its existing mines, copper production has fallen this year to a 25-year low. Ouch.

There is precious little copper supply in the pipeline beyond the four mines currently being brought online, which includes two mines in Chile.

The country hasn’t made it any easier for mining companies, in fact the new government has made it more expensive to mine, hiking royalties to 46%, higher than competing jurisdictions. Some mining companies have put expansion plans on ice. Others are expected to temper their growth plans this year as the likelihood of higher taxes and labor costs dim returns on new projects. Companies are seeing longer delays for permits as opposition has risen from local communities. Some projects have been rejected by the state or by courts on environmental impact concerns.

As Chile cracks down on the mining industry amid a shortage of water, pushback from local communities, and a government wanting a greater percentage of resource revenue, there are also problems in Peru, the world’s second biggest copper producer.

[For] three months, vital highways were choked off by boulders and burning tyres, lucrative copper mines were paralysed and the rail lines leading to the ancient Inca citadel, like much of Peru’s economy, were ground to a halt amid shockingly violent demonstrations. (Al Jazeera, March 10, 2023)

At the end of January, around 30% of Peru’s copper production was at risk. Even after the unrest faded, miners struggled to move tens of thousands of tons of copper concentrate from the Andes mountains to ports.

Peruvian copper exports fell 20% in January and February even as production climbed, leaving mining companies with excess stored inventory that contributed to tight global supplies.

More recently, the country has faced competition from the DRC, which is threatening to knock the Andean nation off its perch as the number two copper producer. Like Chile, Peru has seen copper production plateau, linked to political and regulatory uncertainty.

Reuters noted earlier this month that, while Peru has some $53 billion in pending mining projects, most are long term and have been delayed amid social and political unrest.

Without Chile and Peru, where are we going to get all the extra copper needed to fulfill the dreams of electrification and decarbonization, while maintaining all the traditional uses for the red metal?

There will be a minimum 6.5 million-ton shortfall at the start of the next decade, a substantial output gap that the mining industry has to address with new copper mines.