A junior resource company’s place in the food chain is to acquire projects, make discoveries and hopefully advance them to the point when a larger mining company takes it over. Discoveries won’t be made if juniors don’t have boots on the ground, if they aren’t out in the bush poking around and breaking rocks.

Few exploration companies have the money or technical expertise to “go mining”. For many, the goal is to find a deposit that’s good enough to attract a major who will acquire the asset. Another pathway is for the junior to partner with a larger company. An option or joint venture (JV) agreement is a way for juniors to gain access to the financial and technical resources needed to build the mine.

Juniors are extremely important to major mining companies because they are the firms finding the deposits that will become the next mines. In this way, juniors help the majors to replace the ore that they are constantly depleting in their operating mines. Put another way, juniors find the resources for majors to turn into mineable reserves.

‘Indispensable’ mining and juniors’ place in the food chain

Financings/ capex drying up

One source points out that senior miners have been allocating a relatively small portion of their revenues to exploration spending, with most expenditures invested in developing existing mines and measures to reduce operating costs.

If the seniors aren’t exploring, and when was the last time you heard of a major mining company making a greenfields discovery, it falls to the juniors. But junior mining financing has pretty much dried up; global exploration budgets in 2021 were half of what they were in 2012.

Capital expenditures in mining fell from approximately $260 billion in 2012 to $130 billion in 2020 (corresponding to 15% and 8% of industry revenues, respectively), McKinsey & Company found.

According to Natural Resources Canada, in 2023 exploration spending by juniors declined to $2 billion, down 19% from $2.5 billion in 2022.

But it gets worse, much worse.

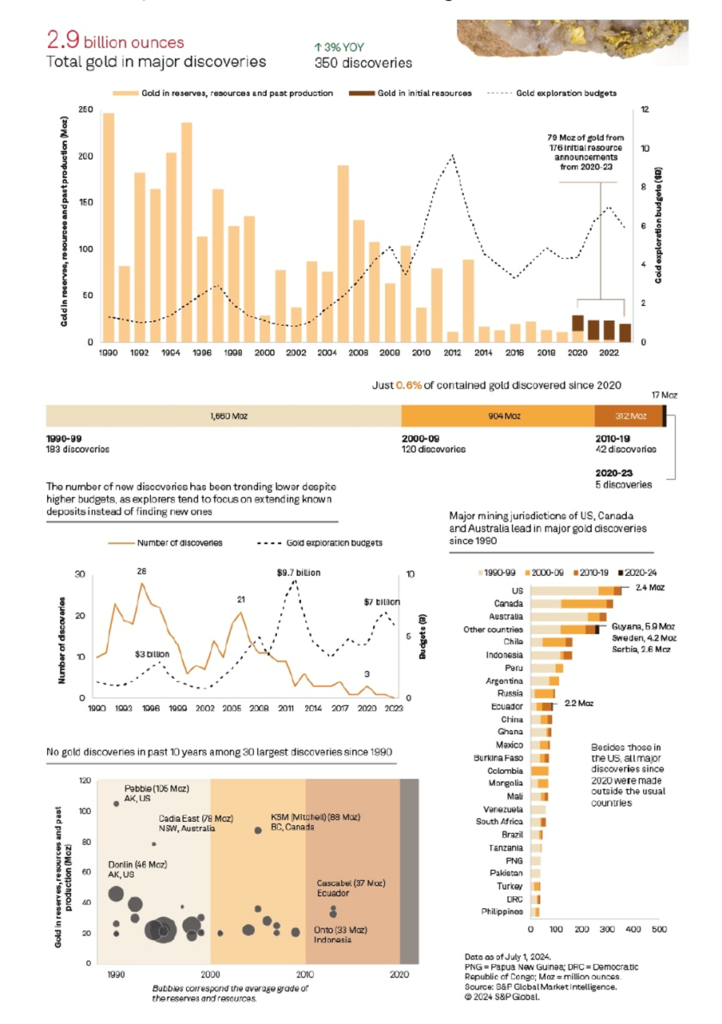

According to a recent analysis by S&P Global, gold discoveries around the world have become more scarce and smaller, dampening the outlook for future supply of the metal.

The report via Mining.com found there have only been five major gold discoveries since 2020 adding about 17 million ounces. A major gold discovery was defined as containing 2 million ounces in reserves, resources and past production.

However, S&P’s report noted that while the number of discoveries and amount of gold continue to grow each year, most of the assets were discovered decades ago….

It also pointed out that the average size of the recent gold discoveries has shrank, at about 3.5 million ounces compared with 5.5 million ounces during 2010-2019. In fact, none of the discoveries made over the past 10 years entered the list of the 30 largest gold discoveries.

One of the graphs above contains an important statement. It says “The number of discoveries has been trending lower despite higher budgets, as explorers tend to focus on extending old deposits instead of finding new ones.”

The S&P report says, “In addition to analyzing past discoveries, we have examined prospects using our data on initial resource announcements, which we track monthly… we identified 176 initial resource announcements with a total of 79Moz of contained gold.”

“Only 78, or 44% of these announcements are from greenfield assets while the rest are from newly discovered deposits within existing projects, demonstrating the industry’s preference for exploring known assets.”

And then this:

“While not all of these assets will become major discoveries, the increasing number of announcements in recent years brings much needed optimism to an industry that has experienced fewer and smaller discoveries. Since 2017 annual gold exploration budgets have more than doubled, reaching a peak of $7 billion in 2022 after a low of $3.3 billion in 2016. Although budgets fell in 2023 due to tighter financing commissions, they remain elevated compared to previous years. This trend is likely to continue as long as gold prices remain high.

“The higher exploration budgets since 2017 have contributed to more and initial larger resource announcements. From 2017 to 2023, there was an average of 42 announcements with an average of 24Moz of gold each year compared to an average of 30 announcements and 13Moz of gold when gold budgets were declining.”

Let’s decipher what S&P Global is really saying in its report, because either knowingly or unintentionally, it fails to state the obvious: that there is no money for the juniors!

The report ballyhoos the fact that, despite there being a lack of new discoveries in the past decade, increasing gold budgets “brings a tad of optimism for the future of gold supply, as the number of initial resource announcements continues to grow in size and number.”

Optimism for whom? Certainly not junior resource companies.

As for being optimistic on future gold supply, S&P research analyst Paul Manalo said the data supports the firm’s long-held view that the industry’s focus on older and known deposits limits the chances of finding huge gold discoveries in early-stage prospects. No kidding.

“The lack of quality discoveries in the recent decade does not bode well for the gold supply,” said Manalo.

“Based on the latest monthly Gold Commodity Briefing Service, we expect gold supply to peak in 2026 at 110 million ounces, driven by increased production Australia, Canada and the US — countries that also account for the most discovered gold.”

He added that gold supply is expected to fall to 103 million ounces in 2028, resulting from a decline in supply from these countries.

Why would supply decline from these countries? In Canada and the United States, it can take up to two decades to build a mine from discovery to production. Any new mines that started on the development path from 2008 onwards likely won’t add to the gold supply by 2028, because they won’t yet be operational. With few mines in the pipeline in these jurisdictions, mine production must come from existing, increasingly depleted mines.

As for peak gold, it’s already here.

In a world of resource depletion, it falls to gold exploration companies to fill the gap with new deposits that can deliver the kind of production required to meet gold demand, which is currently out-running supply.

The gold market continues to experience tightness due to difficulties expanding existing deposits, and a pronounced lack of large discoveries in recent years.

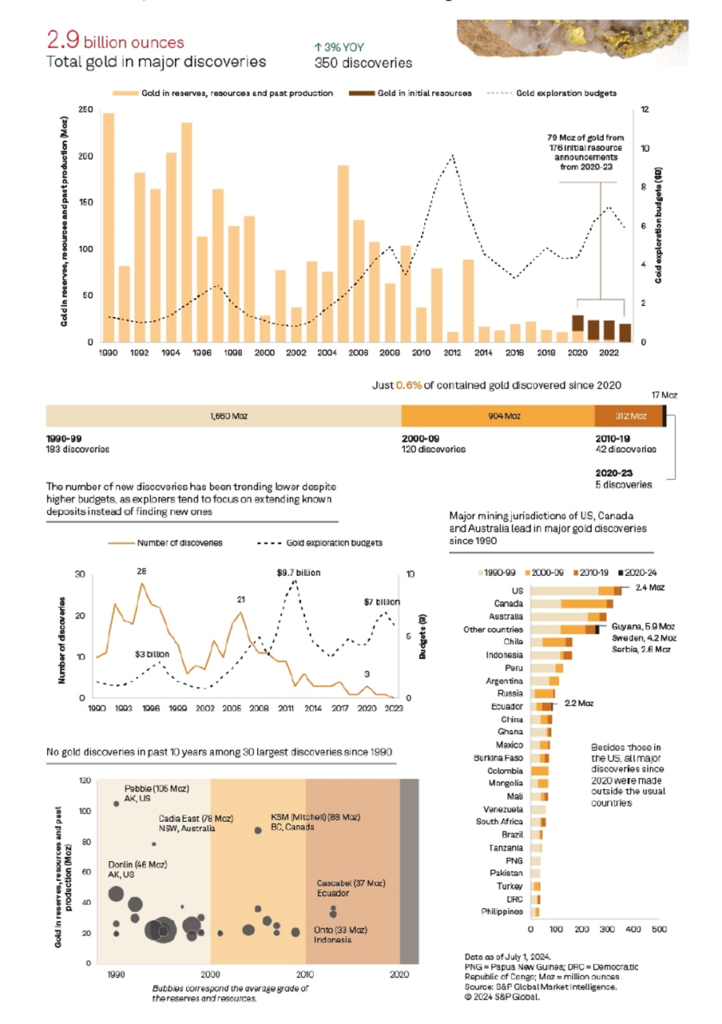

In 2023, 4,448 tonnes of gold demand minus 3,644t of gold mine production left a deficit of 804t. Only by recycling 1,237t of gold jewelry could the demand be met. (The World Gold Council: ‘Gold Demand Trends Full Year 2023’)

This is our definition of peak gold. Will the gold mining industry be able to produce, or discover, enough gold, so that it’s able to meet demand without having to recycle jewelry? If the numbers reflect that, peak gold would be debunked. We’ve been tracking it since 2019, and it hasn’t happened yet.

In the second quarter of 2024, gold demand reached its highest second quarter on record, but supply still failed to keep pace. Mine production of 929.1 tonnes fell short of total gold demand of 1,258.2 tonnes. Only by recycling 335.4 tonnes could Q2 gold supply meet Q2 demand.

It isn’t only gold projects that juniors are having trouble getting financed, leading to fears that a paucity of new deposits will lead to commodity shortages. We see this particularly with critical minerals.

Kai Hoffman, the CEO of Soar Financial, told Kitco Mining in May that despite higher precious metal and copper prices, the generalist investor is missing from resource stocks and “there is no euphoria.”

In terms of financings, Hoffman said the market is trending back to gold and silver, despite $180 million raised in the uranium space in the first three months. “But it’s all later-stage projects,” Hoffman said, affirming the conclusions reached by the S&P report.

An article earlier this year from Investing News Network tackled the problem of junior financing. The issue was a theme both at the Vancouver Resource Investment Conference in January, and the annual PDAC event in March in Toronto.

INN quoted Pierre Lassonde, co-founder and chair emeritus at Franco-Nevada (TSX:FNV) as saying that retail investors have stayed away from the resource sector in favor of the quick money and flashy profiles associated with big tech firms.

According to Lassonde, the tech stocks known as the “Magnificent 7” together represent US$13.1 trillion in market cap, close to the estimated US$15 trillion in gold that has been mined through history, and more than 50 times the US$250 billion combined market cap of all gold equities, including royalty companies.

“(Of the US$250 billion), half of that is six companies, and then the other half, US$125 billion, is about 150 to 300 companies — in the scheme of things for investors, they become irrelevant,” he said.

Lassonde added that asset and fund managers are steering clear of gold due to factors such as disasters, capital costs and bad execution of mergers. He provided the example of Newmont (TSX:NGT), whose share price reached nearly US$90 in April 2022, but as of the end of February had fallen as low as $30 following its merger with Newcrest. It currently trades for $53.11.

Jacqui Murray, partner with Resource Capital Funds, said there’s been a generational shift among private equity funds, with younger managers choosing not to invest in mining for environmental and ethical reasons, especially with the new buzzword, ESG.

In a section entitled ‘Explorers and developers left out to dry’, INN wrote:

Bringing new mines online is a long process. It takes 10 to 20 years to move an asset from discovery to production, and the vast majority of discoveries don’t even make it to the production stage.

This makes funding at the exploration stage critical for the industry to ensure long-term viability and growth. However, while exploration is vitally important, it’s also the most challenging and risky point for investment.

“I took a 10 year span from ’83 to ’93, and I looked at 3,000 exploration companies and what happened to them,” Lassonde said. “Of those 3,000, only five actually delivered mines that opened and made money. So the ratio is appalling, and it got worse in the last 20 years because there hasn’t been the kind of discovery that we saw in the ’80s and ’90s.”

These kinds of results don’t instill confidence. For Lassonde, sifting through companies is part of his day-to-day life. But for regular investors, doing due diligence on the vast array of available stocks can be daunting.

Lassonde also pointed to another fundamental shift within the industry, saying that a steady loss of senior companies in Canada — including Alcan, Falconbridge, Inco and Noranda — over the past 20 years has had a considerable impact on juniors. “These companies not only did research and development, but out of the C$100 million to C$200 million budget they had for exploration, they shepherded probably 50 to 100 companies each at the junior level, because they understood that 50 percent of all discoveries are made by juniors,” he explained.

Despite this top-down loss in investment capital and geological expertise, the number of junior companies is still considerable, and they’re all competing with each other for what funding is available.

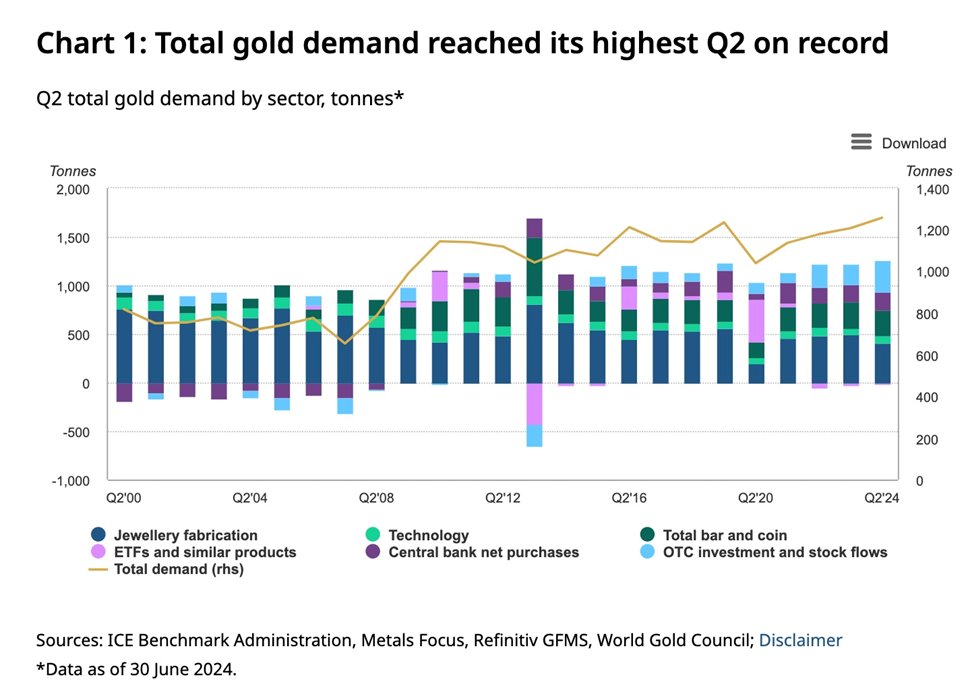

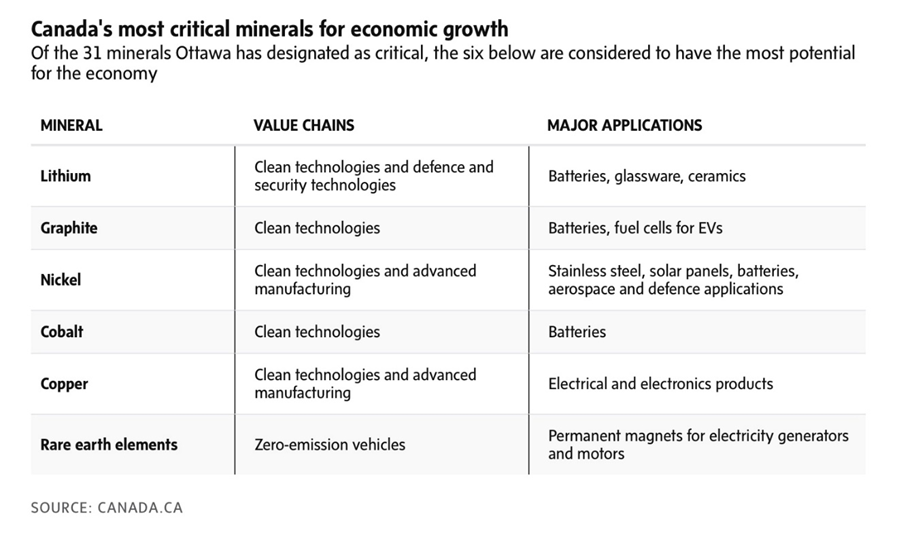

A Globe and Mail article published in November 2023 noted the disconnect between the critical minerals needed to drive the next phase of the global economy, such as graphite, nickel, copper and lithium, and the fact that most of the junior mining companies that are hunting for them are barely treading water, unable to finance the next phases of their exploration.

The industry is completely different compared to two decades ago, when Canadian companies with domestic projects were the envy of the mining industry. Vale’s $19-billion acquisition of Inco in 2006 helped seed a junior mining ecosystem centered in Vancouver and Toronto.

So much of it has vanished – the bankers, the investors and the enthusiasm. In 2010, the mining sector made up 25 per cent of the total value of the Toronto Stock Exchange and the TSX Venture Exchange, more than any other industry. That year, junior miners on the Venture Exchange were able to raise $5.3-billion to fund their exploration and development projects. As of October, they had raised less than half of that, and the sector’s composition of the total TSX has fallen to 13 per cent.

While financings for all sectors are slow this year because investors are recalibrating after the COVID-19 pandemic tech bubble popped, mining has lost its lustre in the Canadian market. There are fewer investment banks providing research coverage of up-and-coming mining companies, and fewer investment advisers paying attention to the sector. When a junior company tries to raise money, there just aren’t as many people willing to listen to the sales pitch.

The struggle to finance terrifies politicians and diplomats because Canada and the United States are losing the global critical minerals war. “Simply put, we don’t have enough of these minerals today to meet the world’s – and our own – growing demand,” David Cohen, the U.S. ambassador to Canada, said in an October speech.

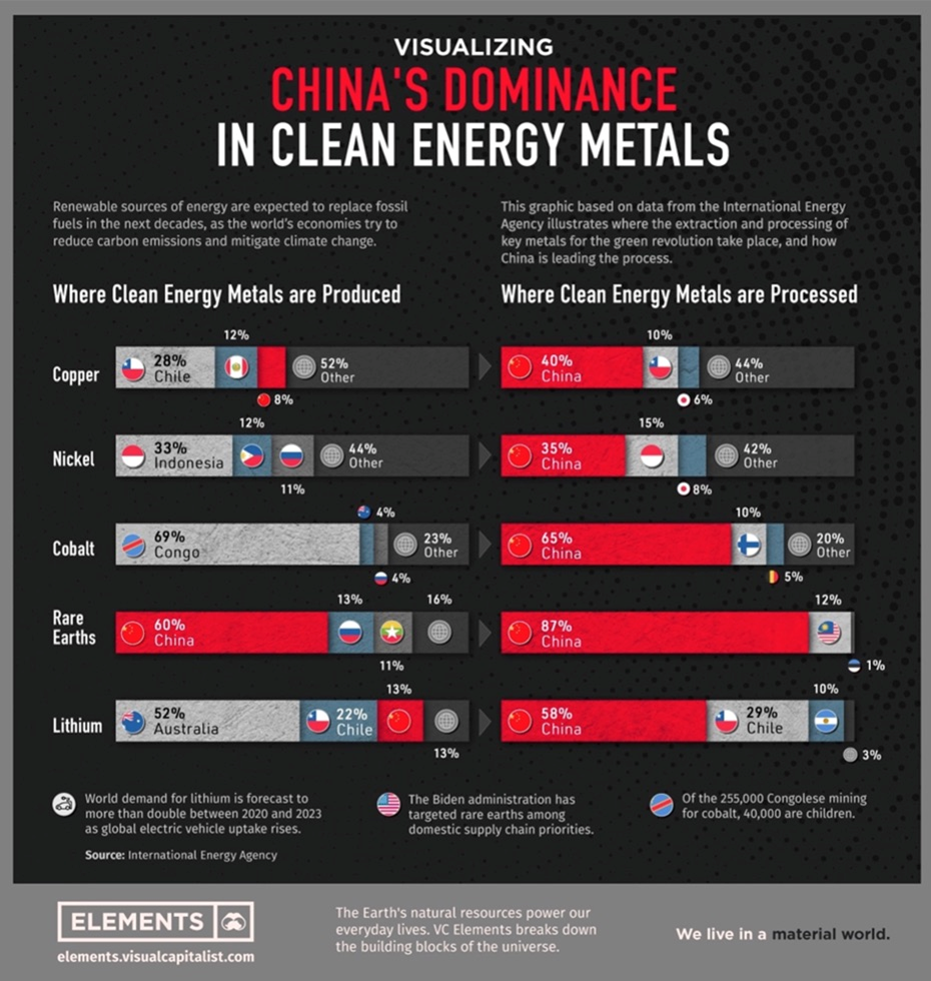

The worry is that China is hoovering up critical minerals and will use them against the West in a geopolitical provocation, the same way Russia held its natural gas supply over Europe’s head when it attacked Ukraine. Currently, China refines more than half of all nickel, lithium and cobalt worldwide.

China threat

The motive behind the United States trade strategy is well-documented — to shed itself of dependence on China while loosening the grip its main rival has on the global supply chain of critical minerals.

When it comes to raw materials for the electric vehicle industry, China is undisputedly the most dominant force on the planet.

For example, almost every metal used in EV batteries today likely comes from there, either mined or processed. Thanks to its technological prowess in refining, China has established itself as the across-the-board leader in the battery metals processing business (see below).

According to the International Energy Agency, the country accounted for roughly 60% of the world’s lithium chemical supply in 2022, as well as producing three-quarters of all lithium-ion batteries.

It also has a tight grip over the world’s supply of cobalt through its mining operations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Over the next two years, China’s share of cobalt production is expected to reach half of global output, up from 44% at present, according to UK-based cobalt trader Darton Commodities.

IEA estimates that China’s share of refining is around 50-70% for lithium and cobalt, 35% for nickel, and 95% for manganese, despite being directly involved in only a small fraction of the mine production.

The nation is also responsible for nearly 90% of rare earth elements, which are essential raw materials for permanent magnets used in wind turbines and EV motors, as well as 100% of graphite, the anode material in EV batteries.

A report by Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy reveals that China now controls roughly 60% of the world’s production of these minerals which are considered crucial to the global energy transition.

For the US, this poses a great security risk, as China could easily decide to weaponize its market dominance, essentially locking America out of the critical minerals supply chain.

Of the estimated 120 million tons of rare earth deposits worldwide, the bulk of those at 44 million tons are found in China. The nation now accounts for 60% of rare earth mining, 85% of rare earth processing and 90% of high-strength rare earth permanent magnet manufacturing.

China cutting off rare earths could prove catastrophic for the US, whose high-tech sectors imported 78% of their rare earth metals from China between 2017 and 2020, according to the US Geological Survey.

The Biden administration’s national security strategy, published in October 2022, identified rare earth supply chains as a major issue. A 2021 Defense Department review also concluded that overreliance on China “creates risk of disruption and of politicized trade practices” that would hit commercial sectors particularly hard.

China previously suspended exports of rare earths to Japan following tensions in 2010 surrounding the Senkaku Islands, which also alarmed those in Washington.

The US has since moved to bolster its domestic rare earth supply chain, with a degree of success. USGS data shows that China’s share of all rare earths produced globally dropped to roughly 70% last year from about 90% a decade earlier.

Nevertheless, China still has a firm hold on the processing of rare earths. This past June, Beijing unveiled a list of rare earth regulations aimed at protecting supplies in the name of national security, laying out rules on the mining, smelting and trade in the critical materials used to make products from magnets in electric vehicles to consumer electronics, Reuters reported.

That news was followed by the imposition of export limits on antimony and related elements in August. Last year China accounted for nearly half of all mined output of the metal, used in military applications such as ammunition, infrared missiles, nuclear weapons and night vision goggles, as well as in batteries and photovoltaic equipment.

CNN quoted rare earths analysts at China Securities saying that increasing demand for arms and ammunition due to wars and geopolitical tensions was likely to see tightening control and stockpiling of antimony ore.

Last December, China banned the export of technology to make rare earth magnets. Beijing has also tightened exports of some graphite products, and imposed restrictions on exports of gallium and germanium products widely used in semiconductors, CNN stated.

Industry Week gave six reasons why China’s threat to ban critical minerals exports is not a bluff, listed below with light editing:

- China has previously implemented export restrictions and bans. China blocked rare earth exports to Japan in 2010 and banned exports of rare earth processing technology in 2023.

- China could benefit from imposing mineral export bans. Export bans on select minerals would demonstrate that China can retaliate against U.S. efforts to curb technology exports to China—and possibly deter the United States from further restrictions, enabling China to stock up on U.S. technology.

- Chinese mineral producers could likely find alternative customers to the United States. Some developing regions like Southeast Asia have increasing mineral demand from their growing manufacturing sectors that China’s mineral producers could tap into.

- China’s dominance of the critical mineral industry is far greater than Russia’s influence on the natural gas industry. Thus, the consequences of China cutting off critical mineral exports to the United States are likely broader and more severe than Europe dropping Russian natural gas exports.

- The United States and its partner countries likely cannot quickly produce enough minerals to fully replace imports from China.

- The United States would struggle to incentivize enough mineral production in resource-rich countries outside China.

To mitigate the risks of potential Chinese export bans, Industry Week suggests the US government should increase stockpiling, noting the National Defense Stockpile is only around 1% of its 1962 value.

The NDS only has 836 tons of nickel, less than 5% of the Department of Defense’s annual nickel usage, and it currently does not contain any of the four minerals used mostly by the DoD: aluminum, copper, lead and fluorspar.

In addition to stockpiling, Industry Week suggests the US government could offer low-cost financing to US companies to secure offtake agreements with trusted providers, i.e., the “friend-shoring” we previously wrote about. The article notes US automakers are already pursuing offtake agreements for lithium, used in EV batteries.

‘Friend-shoring threatens Western metal supplies

The government should also increase funding for mineral exploration. While we at AOTH are leery of government funding, preferring to raise funds on the market or through private placements, a taxpayer-funded boost to mining wouldn’t come wrong, either. Industry Week states:

Exploration is key for increasing the U.S. mineral supply and decreasing reliance on China. Under Title III of the Defense Production Act (DPA), the U.S. Department of Defense is funding some mineral exploration efforts, including nickel exploration in Minnesota and cobalt exploration in Idaho. Title III also allows the department to fund mineral exploration in Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom, as those countries are considered “domestic sources.”

China’s bans on the export of critical minerals processing technology and on exports of certain critical minerals over the past few months has been met with tough talk from politicians in Canada and the US.

Earlier this month, the Globe and Mail reported that Canada has begun the process to impose tariffs on Chinese batteries and critical minerals. In August, the country hiked tariffs on Chinese-made vehicles from 6% to 106%, effective Oct. 1.

The move puts Canada in line with the United States, which announced plans to increase tariffs on similar items in the spring.

Tariffs of 25% will be applied to some steel and aluminum products made in China on Oct. 15, the Globe stated.

According to CNN, the Biden administration last week finalized tariff hikes on certain Chinese-made products first announced in May.

The tariff rate will go up to 100% on electric vehicles, to 50% on solar cells and to 25% on electrical vehicle batteries, critical minerals, steel, aluminum, face masks and ship-to-shore cranes beginning September 27, according to the US Trade Representative’s Office.

Tariff hikes on other products, including semiconductor chips, are set to take effect over the next two years.

Former President Trump now running for a second term, and Vice President Kamala Harris, have both mentioned tariffs while campaigning. Trump implemented tariffs on about $300 billion of Chinese-made products while in office 2016-20.

President Biden has kept those tariffs in place and decided to increase some of the rates on about $15B of Chinese imports. If elected, Trump has pledged to significantly increase the tariffs the US has on imports from all over the world. He is calling for up to 20% tariffs on every foreign import and has called for an additional tariff up to 60% on Chinese imports. He would also impose a 100% tariff on countries that stop using the US dollar.

Harris has not given many details on her tariff policy other than to attack her opponent’s tariff proposals as a “Trump sales tax”.

Studies have found that American consumers have borne almost the entire cost of Trump’s tariffs on Chinese products, CNN said.

China has launched a complaint at the World Trade Organization over Canada’s EV tariffs, and is already figuring out ways to skirt US tariffs. BYD, China’s largest EV automaker, is reportedly reviewing potential locations for a plant in Mexico that would allow it to bring its cheaper electric vehicles into the United States tariff-free, under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (formerly NAFTA). At least a dozen Chinese electric-car component suppliers have also announced new factories or added to their existing investments in Mexico in recent years, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Conclusion

If the United States and Canada are to lessen the grip that China currently has over our critical mineral supplies, we are playing a dangerous game — poking the bear with a large stick without having a back-up plan as to what happens if the stick doesn’t prevent the bear from charging and ripping out our throats.

By that I mean we currently mine precious few of the critical minerals needed to build an electrified economy, and we lack the smelters for processing them and the technical know-how to do so.

By pissing off China with tariffs, are we not cutting our nose to spite our face? We don’t want to see an influx of cheap Chinese-made products dumped on North American markets, but surely the solution is to mine, process and manufacture the products that we need at home, rather than stopping them at the border.

The situation is dire and it starts with mining. The S&P report is misleading in that it shows that major mining companies are exploring for more gold, but they are doing it on their own properties, sometimes mining around the edges of deposits discovered decades ago.

They are doing nothing to go out and find new mines, but that has never been a major’s job. It’s the job of juniors to discover new mineral deposits but they are not being financed; they literally have no money and are conducting financings at 5-10 cents, thus blowing out their share structures.

Or doing bought-deal financings to institutional minded investors who are only too willing to sell their immediately saleable (no 4 month hold) shares and ride the warrants till exercise.

If North America doesn’t have the metals it needs. that China has locked up, and then China turns around and says we’re not selling them to you, what are we going to do? Right now the industry’s solution is to go poking around their own brownfield projects to find more metal to mine. It’s a far cry from what we are going to need.

It is elemental to the mining industry that the juniors are well financed, deposits have a shortened path to production, say five years like in Scandinavia, versus up to 28 in the US. Juniors need to be out in the bush making discoveries.

Because only with the help of juniors can mining solve its existential problem of getting the resources that are currently owned by its adversaries. Junior resource companies find the resources miners then buy and turn into their mineable reserves.

In fact, I don’t think it’s much of a stretch to say that without financed juniors, without a safe and secure supply of metals, without security of supply, without refineries and smelters, and without the technological knowledge to manufacture magnets and anodes for example the developed economies of the western world are very much at risk if supplies of these critical metals, and associated technologies, come from our competitors.