- System Failure

- Limited Control

- An Extraordinarily Tight Labor Market

- Employment Is More than a Simple Financial Transaction

- Everything Shortage

- Hedging Opportunity

- New York, New York, and Dallas

At the risk of overusing a favorite metaphor, today we’ll talk about sandpiles. My past sandpile stories focused on financial crises. The same principle holds in any complex system, though. Everything works until suddenly it doesn’t. As Minsky said, stability breeds instability. Then one additional grain of sand triggers a collapse.

Today’s financial system is complex but our logistical systems are, too. The modern economy that brings us so many wonderful goods and services is a breathtakingly complicated web of production, transportation, and storage capacity… and most important, the marvelously complex division of labor among millions of people around the world. When it all works, we (at least in the developed countries) have on-demand access to luxuries unimaginable even a few generations ago, and we regard it as normal.

The problem is complex systems are inherently fragile. The optimization that makes them cost-effective also removes the redundancies that make them resilient. Things can fall apart quickly when some unforeseen event occurs. Or an unforeseen sequence of events, which is what’s happened.

The ongoing, intensifying supply chain problems are raising costs in ways that add broad inflation pressure everyone will feel. And the zeitgeist in the workplace is literally changing before our eyes. Patterns that have held since the Industrial Revolution are changing. If you’re an employer, it is frightening. If you’re a researcher, it is fascinating. And when you are a consumer, it becomes frustrating. Whether you feel it directly or not, you’re going to feel the downstream effects.

Remember those first weeks in January/February 2020 when the virus emerged in China? Many in the West initially (and optimistically, it turned out) thought it would stay there. News focused on the closure of much of the Chinese economy, and the spillover effects on the rest of the world missing its shipments.

Now, with vaccines helping on the medical side, the economic and supply chain effects are again top of mind. Increasingly they are personal experiences, not just news stories. You’ve probably been unable to find favorite products, suffered shipping delays or otherwise had to modify once-routine plans. Sometimes these are minor annoyances. But for a business depending on a steady flow of inventory or components, it can be a catastrophe.

Why is all this happening? It’s not any one cause. Remember, we are talking about not just a complex system, but multiple complex systems interacting with other complex systems. Getting even a simple device manufactured at scale is a ballet dance in itself. Then it has to get packed, loaded, shipped across the continent or the sea, unloaded and delivered to the place you buy it. Every step in the process is a chance for something to go wrong. And, this all being a giant sandpile, it’s vulnerable to collapse.

Last week George Friedman, being a geopolitics expert, noted these shipping and production problems are what you expect in wartime, when countries are shooting at each other. They aren’t normal in a growing global economy. Everyone has incentive to avoid them. So why are they happening?

George sees “many systems failing and interacting at the same time,” the key one being a global reduction in labor supply. But what’s causing that? You can point to COVID restrictions, government benefits, inadequate child care, etc., but they still don’t explain the magnitude of what we are seeing. This lack of clarity is troubling.

This is what is most frightening about this development. Many agree that a labor shortage is a key driver of the supply chain problem. Yet the dominant theories of what happened, while not refuted, have many weaknesses. That means that there must at least be additional explanations. So, we are facing a depression, originating not in financial events but in the displacement of people, transport and other elements. Facing a system failure with a known cause is one thing. Facing one for which you have no model is another.

To be clear, George knows “depression” is a strong word. He’s not saying we are there yet. He thinks we could get there if these problems continue and intensify—and it’s hard to argue they won’t, given our inability to explain them, much less solve them. A logistics system collapse would be unlike a financial system collapse, but maybe even more harmful. That’s why early signs of it should concern us.

We can get a hint of where the US may be headed from events in Britain, where a severe fuel shortage recently hampered activity. The problem wasn’t the petrol itself, but a shortage of truck drivers to deliver it. But that didn’t especially matter to people lined up at gas stations. The crisis is now easing somewhat with help from military drivers.

The causes are murky. Many point fingers at Brexit-related immigration changes, but visas are available. The drivers weren’t on strike. No natural disasters occurred. The country had dropped most COVID restrictions months earlier, so people weren’t suddenly driving more. We just don’t know and, as George noted, that’s the frightening part.

As for the US, I’m not aware of any widespread fuel shortages but there are scattered reports. Here’s one from the Dallas area.

Source: Twitter

I don’t know how common this is, but if it’s really persisted for a month then it could get worse. Driving a fuel tanker is hazardous work requiring specialized skills and training. Now, with many other jobs available at competitive pay, it’s no wonder drivers are scarce.

Delivering fuel (or anything else) requires an entire chain, each link of which is vulnerable. Break any one of them and nothing moves. It doesn’t matter if the US has plenty of gasoline if it can’t reach your vehicle.

Heartland Express, a major medium- to short-haul trucker, said in its earnings report yesterday:

“We also believe that hiring and retention of employees has reached levels of unprecedented challenge across our industry for both carriers and shippers. We continue to partner with our customers who have had to navigate their own employment-related disruptions in order to deliver our strong operating results during the quarter. We believe that this shared challenge of hiring and retaining both drivers and other supply chain critical employees will continue in the year ahead. To address that challenge, we have increased wages and enhanced the compensation features for our drivers multiple times in the last 12 months.”

Major shipping company JB Hunt echoed the same theme. Labor is clearly a big part of the problem, so let’s go deeper.

An Extraordinarily Tight Labor Market

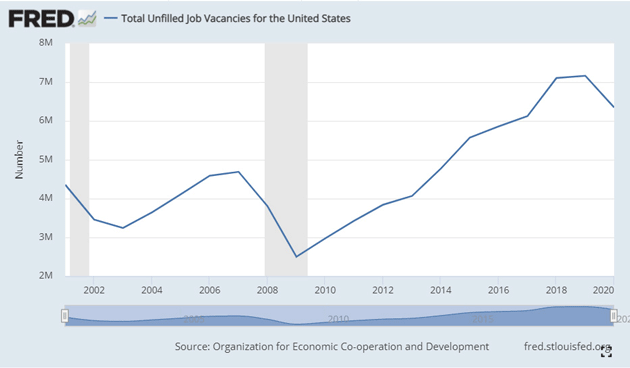

Unemployment is officially a 4.8%. The St. Louis Fed’s FRED database tells us there are 7,674,000 officially unemployed workers. There are another almost 6 million workers who are technically not in the labor force who would like a job. The chart below shows over 6 million jobs available right now.

Source: FRED

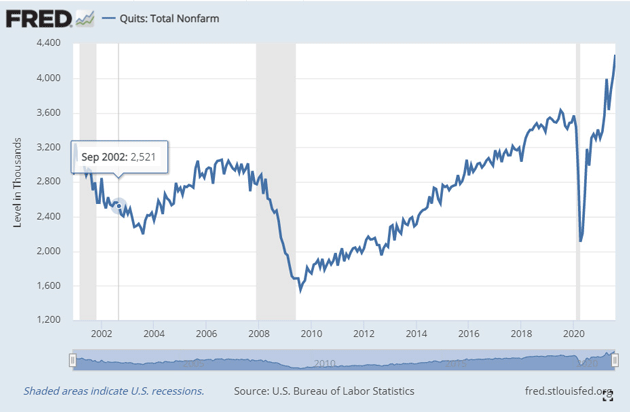

But something interesting is happening. We just came off a recession, barely recovering in a Stumble-Through Economy. But in the last 12 months, 15 million people have quit their jobs.

Back out the “quitters” and you actually get a 1.8% unemployment rate, which is incredibly tight. Now, many of the quitters will find other jobs (or already have). The Atlanta Fed tells us that the average “quitter” gets a 5.4% wage increase in the next job.

But no matter how you look at it, not only is the labor market tight, something is clearly happening underneath the topline data. Look at the chart on quitters below. We’ve never seen anything like this, and the same is happening around the world.

Source: FRED

Employment Is More than a Simple Financial Transaction

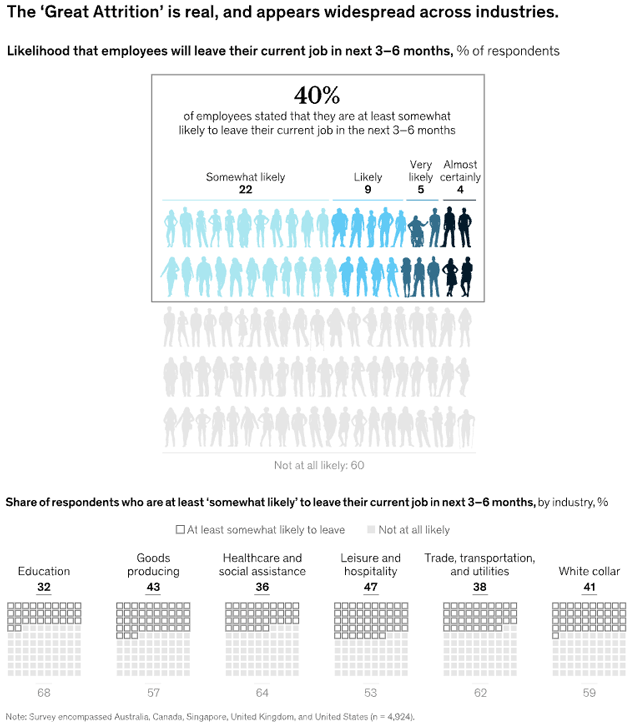

McKinsey has a fabulous new report on what workers really want. I’ll try to summarize but it is worth your time to read it, especially if you’re an employer.

If the past 18 months have taught us anything, it’s that employees crave investment in the human aspects of work. Employees are tired, and many are grieving. They want a renewed and revised sense of purpose in their work. They want social and interpersonal connections with their colleagues and managers. They want to feel a sense of shared identity. Yes, they want pay, benefits, and perks, but more than that they want to feel valued by their organizations and managers. They want meaningful—though not necessarily in-person—interactions, not just transactions.

In studying Australia, Canada, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and the US, McKinsey found 40% of surveyed workers said they are likely to quit within the next six months. Wow!

Source: McKinsey & Co.

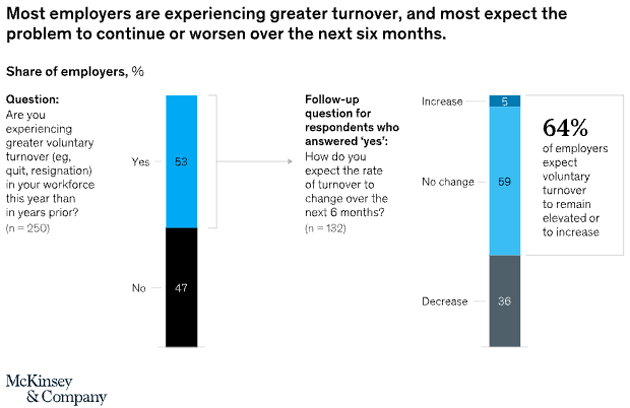

Employers expect this to continue:

Source: McKinsey & Co.

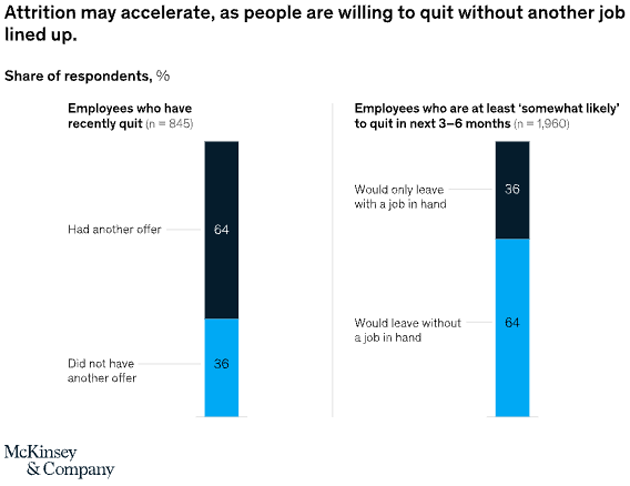

The fascinating thing to me is the numbers of people willing to quit their job without having another job lined up:

Source: McKinsey & Co.

I recently talked to one hospital executive. If they mandated all their nurses to have vaccines, they might lose up to 20% of the nurses. You can’t replace a nurse with the National Guard or an untrained civilian. Some airlines are finding out you can’t replace pilots. I have a friend in New Orleans who is a major construction and real estate developer. He is being asked to take on more projects than ever but he can’t find workers at any price.

Remote work opportunities are attracting some employees to change jobs even for companies in other states.

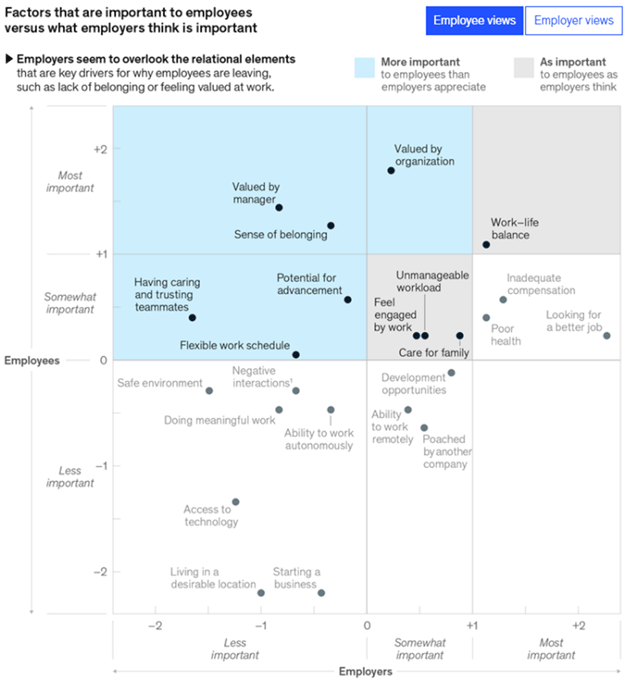

And this is the killer chart. While employees still value money, there are other things higher on the list.

Source: McKinsey & Co.

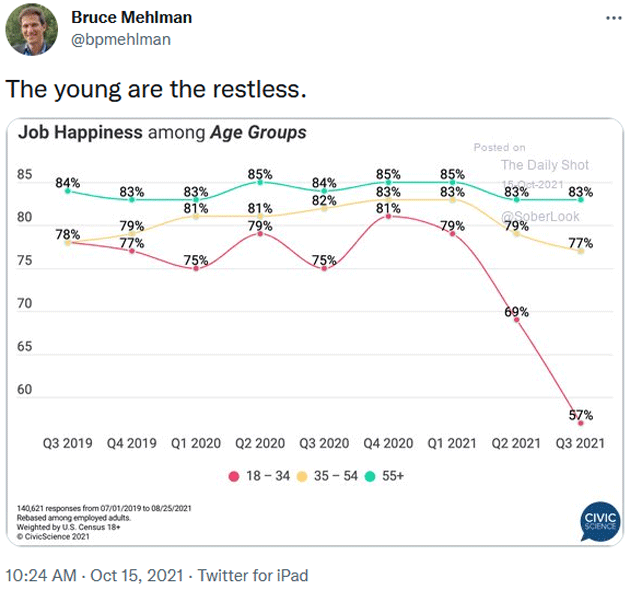

Not surprisingly, what workers find important is not necessarily what employers think they want. There is truly a clash of cultures. And of generations, too.

Source: Twitter

A couple of points. First, this frustration with work has been building for decades. It has to do partly with income and wealth disparity, and partly with the frustration of life. People see others seemingly benefiting while they’re working their asses off (that’s a technical economic term). It’s like the Burt Bacharach song from Alfie.

What's it all about, Alfie?

Is it just for the moment we live?

What's it all about when you sort it out, Alfie?

In the COVID recession, people were forced to not work, or to work in very difficult situations. This made them rethink age-old questions. What do you want out of life? Long-haul truck driving is lonely and difficult, and from the data unhealthy. Most of my readers are retired or hold jobs they find fulfilling. But if you work in the lower levels of the hospitality industry or other dangerous jobs, if you don’t feel appreciated, maybe you start thinking about changing careers even if you make good money. The McKinsey data clearly shows that’s what is happening.

Second, COVID has introduced pressures into life that weren’t there before. And if you don’t feel comfortable going out in public, it’s difficult to say “I want a job” where you would be working in public. Throw in the political divide of mandates versus non-mandates, the finger-pointing, the politicization of the virus, the mis- and disinformation about vaccines and the virus, and you have a witch’s brew of reluctant workers.

Wages are important but less than many employers think. They are treating the problem as if it is a transaction. If I offer you more money, you should want to work here. But potential employees are obviously looking for something more than a mere transaction (money) to be the center and focus of their own personal lives. It is truly a clash of cultures, kind of like Baby Boomers not understanding Gen X or Y.

Worker shortages plus logistical difficulties plus rising demand add up to big economic problems. Shortages are becoming common in all manner of goods. Louis Gave listed three reasons in a recent note.

The first is the big data revolution. The newfound ability to measure everything has given companies and governments an incentive to eliminate redundancies and “optimize” the delivery of products and services. Unfortunately, systems with no redundancies are inherently fragile. When challenges appear, prices surge.

The second factor is previous policy interventions. If three years ago Donald Trump had not announced that China would no longer be allowed to import semiconductors built with US technology, would the world be facing the same chip shortages today? And if governments had not been so vocal about transitioning from carbon to renewables, would the world be seeing the current surge in energy prices?

The third, and most important, factor is today’s lack of workers. This was clear in the release Friday of disappointing US job numbers for September. Payrolls came in significantly below expectations. Yet the unemployment rate still fell, implying that US labor participation continues to deteriorate.

The real problem is we have very limited control over all these factors. Adding more redundancies might help but would take time and add costs, as Louis notes. It wouldn’t solve the near-term problem.

These kinds of nagging problems generate higher price inflation, but often in ways our data misses. If you can get what you need at the same price as a year ago, but you have to wait six extra weeks for delivery, you are not receiving the same benefit even though your cash outlay didn’t rise.

Much depends on how discretionary the item is. If you’re a chef and you can’t get your favorite sauces, you’ll just get creative and use something else. The restaurant customers may never know. If you want to paint your house and can’t get paint, then it may look a little shabby for a while. Annoying but not the end of the world.

But some goods aren’t discretionary. Energy shortages hurt because everyone needs fuel and electricity. The stress level shoots from zero to infinity overnight in situations like last winter’s Texas blackout. As do wholesale power prices, which eventually get passed on to consumers.

The same systemic complexity that generates some of these problems also diffuses and disguises their impact on inflation. Producers have many ways to deliver less value without raising prices. Here in Puerto Rico, Costco didn’t raise the price of lamb chops. They just put fewer lamb chops in the package. The government’s “hedonic adjustments” are supposed to capture this. Maybe they do, but I have my doubts.

As the old saying goes, the solution to high prices is high prices. People stop buying and producers have to find ways to charge less. At the macro level, the solution to inflation is recession—or if not outright recession, at least lower growth.

This may be happening. Many forecasters, including those at Goldman Sachs and the IMF, are cutting their 2021 full-year GDP forecasts as it becomes clear the recovery won’t continue at this pace. Mainstream forecasters are projecting little or no growth in China for the last half of this year. Coming off 6 to 8% growth, that will feel like a recession. Slower growth should reduce the demand driving these supply chain snarls.

Earlier this year I was confident that would happen, that our high debt load would suppress economic activity enough to keep inflation transitory. Lately I’m rethinking that, and the logistics issue is a key reason. As my friend Brent Donnelly quipped, “I’m wondering what the return policy on my Team Transitory T-shirt is?”

As aggravating as all this is, consumers and businesses are still showing unexpected patience and finding ways to cope. If we’re mostly willing to live with these conditions, then they’ll probably continue. Growth may diminish but not too much.

The jury is out, but I want to leave you with a positive thought. Problems like this spark creativity that makes things better for everyone. In researching this letter, I read an excellent article in The Atlantic covering similar themes. The author, Derek Thompson, called it the “Everything Shortage.” He had a hopeful conclusion about where it could lead (emphasis mine).

Our dearth of manufactured parts and containers is part of a broader crisis of manufactured scarcity in America. A protectionist and anti-growth instinct runs through government, yielding not only a flat-footed CDC and a tardy FDA but also sharp restrictions on housing construction, immigration, and the licensing of new professionals and tradespeople. Focusing on the redistribution of income and goods is natural for today’s progressives, who tend to emphasize the virtue of equality. One lesson of the Everything Shortage is: You cannot redistribute what isn’t created in the first place. The best equality agenda begins with an abundance agenda.

Today’s crisis is an opportunity to emphasize a new philosophy of what The New York Times’ Ezra Klein calls “supply-side progressivism,” which sees value in this across-the-board abundance. This approach might start by prioritizing policies that reduce the cost of housing and health care, and reshoring the production of materials that we deem essential to national security during a pandemic or an unrelated supply-chain calamity. Decades from now, we might look at the legacy of the pandemic, and see that it took a global crisis of choke points to teach us that real progress begins by removing the choke points at home.

That thought should resonate for those of all political stripes. Progressives who want equality should want equality at the highest possible level. Conservatives who value opportunity should recognize we will all have more opportunity if we remove the barriers that block it. In the balance between those are some helpful policies we can all agree on.

It’s time to hit the send button, and there’s another whole letter which we will do next week on why Federal Reserve monetary policy can’t fix this problem, and in fact the current policy may be the exact wrong prescription. Not to mention some of the proposed legislation and regulatory fixes. Not all, but some. But that’s for next week…

I talk a lot about the economic quagmire we find ourselves in, but let me present a solution: physical gold. You don’t need to be a history buff to figure out that gold has been a highly effective inflation and crisis hedge throughout the centuries.

For many years, I’ve been buying a little gold every month for my grandchildren—so they’ll have a safety net that maintains its value when the road gets rocky. I believe everyone should have some gold in their portfolio.

You can find out why in this special report we’re making available free to my readers this week. It’s called, 5 Reasons Why Portfolios Perform Better with Gold. I recommend you read it. You can download it here.

New York, New York, and Dallas

I’m still heading to New York in two weeks, but not staying the weekend, as Halloween in New York sounds lonely. I will return to NYC two weeks later for a book launch party and more meetings before Thanksgiving in Dallas.

This letter is already too many words so I will just hit the send button, wish you a great week, and remind you to follow me on Twitter. I really do have some fun there.

Your happy to be a writer in paradise analyst,

|

|

John Mauldin |

P.S. Want even more great analysis from my worldwide network? With Over My Shoulder you'll see some of the exclusive economic research that goes into my letters. Click here to learn more.