Sometimes two seemingly opposite things can be true at the same time. Right now, we can correctly say inflation is both a) better than it was and b) higher than it should be.

But those are still economic generalities. They don’t necessarily describe your unique part of the economy.

The fact inflation is so highly individualized—a big problem for some, a non-event or even beneficial for others—greatly complicates the discussion. But in the long-term macro picture, inflation is bad for pretty much everyone… which is why policymakers need to keep it under control.

We tried to unravel this tangled web (along with others) at the Strategic Investment Conference. Many different speakers and panels discussed inflation from various angles. In fact, it was hard not to discuss inflation. You really can’t understand the economic outlook otherwise. The final panel mentioned inflation 29 times. You can look at the transcripts and sense how important inflation is when discussing the economy.

In today’s letter I’ll share a few of those interesting conversations, then talk a little about the newest inflation data.

Boom Times

As I continuously say, inflation is never “good.” Even a low inflation rate will slowly but surely devalue your savings and raise the price of essential goods and services. Even 1% inflation means that you would lose 75%+ of your (pick a currency) buying power over a lifetime.

In the short term, however, inflation can definitely feel good, at least if you are on the right side of it. Asset price inflation, certainly associated with general inflation, makes investors smile. We like it when our stocks and real estate go up. But it is a stone-cold _____ when you want to buy a home or high-valued index funds.

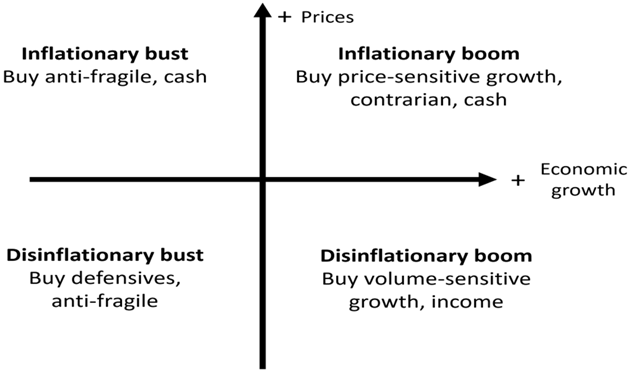

Louis Gave believes the US, and indeed the whole world, is entering an “inflationary boom” period. He uses that phrase in the specific context of Gavekal’s longstanding four-quadrant economic framework. It shows the four possible combinations of high/low growth and high/low inflation. This interaction of economic activity and inflation is what defines asset prices.

Source: Gavekal

Louis had a nicely succinct explanation of how inflation and growth can coexist, which I will quote from our transcript.

“Now, today, we are, like I said, very firmly in an inflationary boom, pretty much every piece of economic data, every piece of commodity price, every market behavior seems to be pointing in that direction, which is somewhat of an anomaly because fundamentally, capitalism is a deflationary force. Most businessmen, most entrepreneurs wake up in the morning thinking, ‘How can I produce more with less? How can I produce more with fewer commodity inputs, with fewer workers, with less land, with less energy?’ you name it. Capitalism is always trying to produce more with less. And for the past 30 or 40 years, I assume most of us on this call—unless you have people who are over 75—most of us on this call have basically spent our whole careers living in deflationary worlds. And indeed, in a deflationary world, you always ask yourself the question, as you see interest rates go up, as they are going up today, you ask yourself the question, as these interest rates go up, ‘Are they going to break the back of the economic expansion?’

“But in an inflationary world—and I’ll go into a second as to why we are an inflationary world and why we will stay there—in an inflationary world, rising interest rates are seldom enough to break the back of bull markets because the reality is, nominal growth tends to go up just as fast as interest rates. And so, if you have interest rates that move from 0% to 5% but nominal growth that moves from 2% to 7%, then with 7% nominal growth, companies, individuals, households can pay off their debt, and you don’t get into the bust phase of the cycle. And instead, in inflationary cycles such as we saw in the 1970s or, I would argue, such as we saw in 2006, 2007, 2008, you really need a one-two punch. You need to knock the economy on its back. Most households, most businesses can take one punch on the nose. You can take a punch and still stay standing. So you get higher interest rates, it hurts, but you’re still standing.”

That’s where we are right now. The Fed’s tightening had little effect because nominal growth grew even faster and is still doing so. Why? Louis sees two drivers. First, the demographic labor shortage is raising wages for low-end workers with a propensity to spend most of it. This boosts demand for all kinds of products. The second factor is an unfolding boom in emerging markets—not just China. This is raising global demand for energy and natural resources.

Louis went much deeper into all this than I can fairly summarize here. You should definitely read the transcript and flip through the 78-page chartbook he distributed to SIC attendees.

Debt Burden

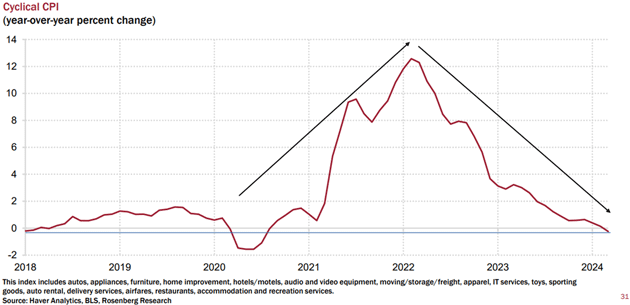

David Rosenberg is on the other side of this. Rather than an inflationary boom, he is more concerned about a deflationary bust. He thinks the latest inflation was indeed cyclical, i.e., “transitory” and has now mostly faded.

Some prices remain elevated and we certainly notice them: housing, healthcare, home and auto insurance, to name a few. But the items whose demand tends to rise in a booming economy are getting less expensive, not more. He shared this index of such “cyclical” inflation, which is now back in its pre-COVID range.

Source: Rosenberg Research

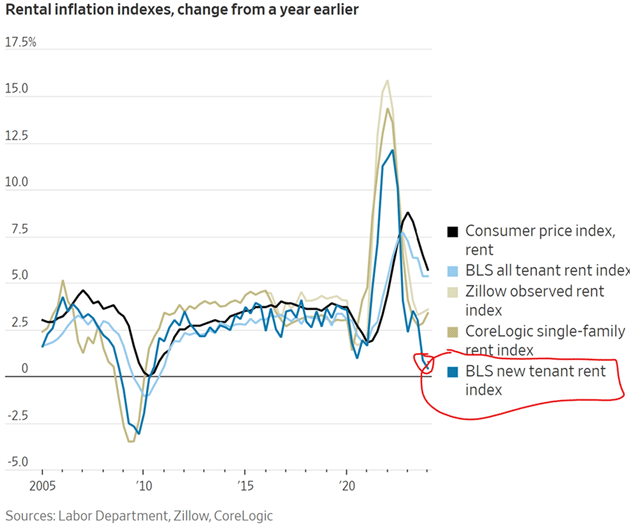

Housing is, of course, the biggest hurdle to overcoming inflation. But housing inflation is also fiendishly hard to measure. Aside from the tremendous local variation, what price should we watch? Home prices? Monthly mortgage payments? Rental rates? Imputed rental rates (i.e., the “owner’s equivalent rent” we’ve discussed before)? And do we look at rates for new leases/purchases or existing contracts? There’s no fully satisfying way to do this.

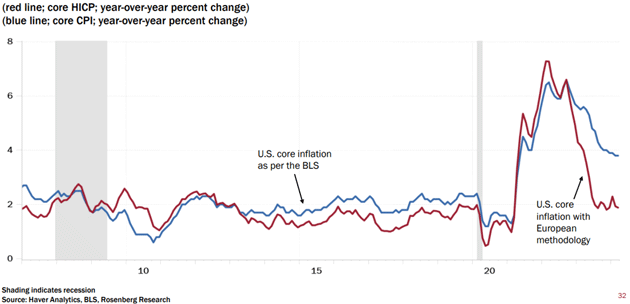

Dave pointed to a different measure used in Europe, the “Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices” or HICP. This is similar to CPI in most ways but excludes owner-occupied home prices. Applying that methodology to the US data reveals something interesting.

Source: Rosenberg Research

Using HICP, core inflation in the US is considerably lower than CPI shows. In fact, it’s probably closer to the Fed’s 2% target than April’s lower-than-expected 3.6% core CPI rate.

Of course, we can play with methodologies and get different results all day long. But the HICP comparison is, if nothing else, a good indication of how much high housing prices affect our inflation data. This matters to policy; Dave expects the European Central Bank to cut rates this summer, in large part because HICP gives them room to do so.

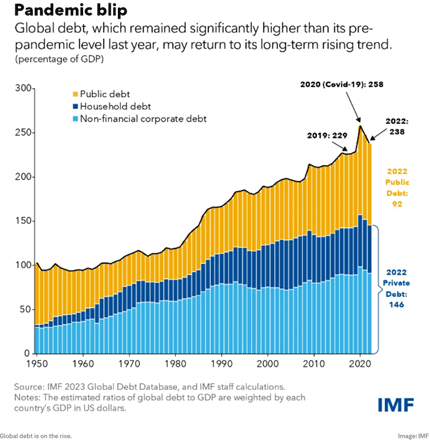

In Dave’s view—and I think Lacy Hunt would agree—inflation is returning to the pre-COVID status quo where it ran 1‒2% no matter what the Fed did. This is the growth-suppressing effect of excessive debt, which is growing steadily more excessive. And not just in the US; here’s the latest IMF global data.

Source: IMF

The governmental share of the debt is widening, but the point here is that total debt of all kinds is returning to the previous trend and is often not being used productively. Lacy Hunt’s math says this makes a sustained economic boom difficult, and without one inflation will also return to trend.

In this view, the COVID-era inflation emanated mainly from artificial disruptions that prevented supply from meeting demand. With those now fading, so are the higher prices.

(Sidebar: The chart above shows global debt was about $250 trillion at the end of 2022. Global GDP at that point was slightly over $100 trillion. Global debt to GDP is therefore near 250%. We are all turning Greek, Italian, or Japanese. Or lately, even American.)

This may sound inconsistent with Louis Gave’s view, but it’s really not. They differ on timing. Louis says the inflationary boom could be knocked out by tighter fiscal policy, i.e., higher taxes and/or reduced government spending. He doesn’t expect those to happen soon but at some point, they will. The economy’s ability to produce tax revenue sufficient to support so much debt is not unlimited.

David Rosenberg explained it nicely in response to an SIC audience question.

“In terms of the debt load, to me, it's a future tax liability. It is something that leaves me more bullish on Treasuries than the opposite because the debt burden is going to prove to be deflationary, not inflationary. And as we've seen in many parts of the world before, this debt is not inflationary. People who think that we can inflate our way out of it are totally mistaken. You can't inflate your way out of these debts because the inflation creates, as we saw just the past couple of years, its attacks on the poor and attacks on the elderly, and the Fed will resist it. There's no social appetite to having inflation eat away our debts.

“There's going to have to be structural changes at some particular point in time, but the debt itself is a deadweight drag on aggregate demand. It's actually one of the reasons why I think rates and inflation are going to be coming down. People have it half-assed backwards, they think that the debt is inflationary. No, I think the Japanese experience taught that debt at these levels is definitely disinflationary.”

The question is when/how this disinflation arrives. Dave thinks it will be soon and via recession.

When Stability Is Not Enough

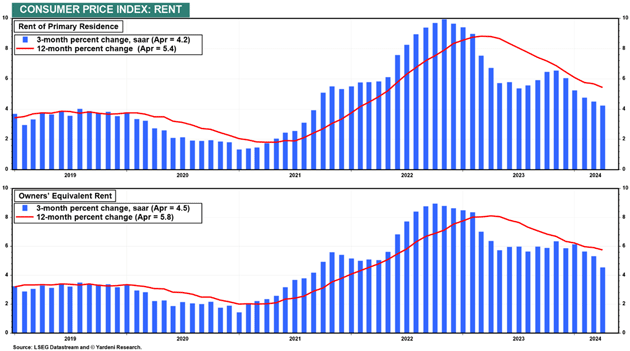

The latest CPI data covering April, released this week, showed a lower-than-expected 3.4% 12-month change. Core CPI (excluding food and energy, so heavy on shelter) dropped to 3.6% vs. 3.8% in March. Yet the CPI rent component rose 0.4% for the third month in a row. How does that make sense?

As noted above, it all depends on what data you think is most relevant. My friend David Bahnsen sent around this handy graph comparing different rental benchmarks.

Source: David Bahnsen

Note the part he circled there. Looking only at newly leased units, rate growth has plunged almost back to 0%. This suggests supply and demand are beginning to align, though of course not everywhere. We should also note that the end of rent inflation, while nice to see, doesn’t reverse the previous increases. It simply means rates are holding steady at what is, for many, a painfully high level.

I have some personal experience with this. We bought houses at inflated prices coupled with high interest rates in the early ’80s. Ugh. Then the savings and loan crisis collapsed housing prices in Texas and some other states. I sold my inflated-price home at a small loss but bought another much nicer home with enough room to take care of 7 kids at a 70% discount to the asking price of a few years earlier.

But that kind of housing price deflation is not on the horizon right now. Four of my eight kids have had to move in the last year, switching jobs and towns. And perhaps housing inflation has flattened (in terms of rental equivalents), but apartment and home rental prices are often still up 25% or more from three years ago. Can we say sticker shock? And none of their incomes are up that much. Childcare is through the roof. These are common experiences of well more than 50% of the country.

Actual rent deflation will require more supply and/or lower demand. Many new properties are under construction, which will help in some locations, but demand is staying strong, too. Due to NIMBYism and other reasons, meaningfully expanded housing availability in the places where it’s really needed is proving difficult.

This, in turn, feeds other kinds of inflation. Labor-intensive service businesses (think hotels, restaurants, etc.) in high-rent areas must raise wages so workers can either afford to live nearby or spend extra time and money commuting from the places they can afford to live. Higher wages are good for workers, but not when they simply cover a higher cost of getting to work.

Nevertheless, rent stability is the first step to rent affordability. If wages keep rising while housing costs go flat or even fall, we could start to see relief on some of these inflation pressures. But I suspect it will be a slow process. It is certainly not happening fast enough for my kids or, I suspect, the majority of the country.

My Thoughts on Inflation

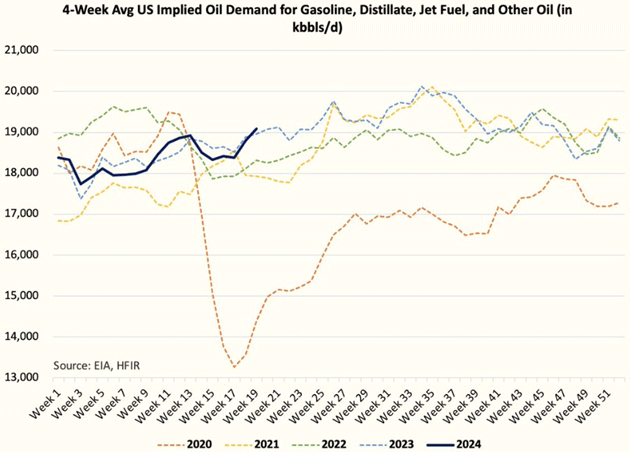

Energy inflation is poised to rise. Everybody is aware of the problems of Iran, Israel, and oil. And Russia and the general geopolitical tensions. But so far, we seemingly have worked around the disruptions keeping oil in the $80 range.

Venezuela and Guyana are probably not on your bingo card but they should be. A source tells me two Russian military vessels are heading to Venezuela near Exxon’s offshore rigs. Totally legal. The Venezuelan military is acting like it intends to invade Guyana. Maduro evidently thinks that the US will not impede them, and Putin and Xi are certainly encouraging him. Whether or not the US decides to get involved, significant disruption to oil production is likely if there is a conflict. My sources tell me that the South American situation is more volatile than markets are currently pricing.

A spike in oil prices to over $100 is well within reason if there is a conflict in either Guyana or in the Middle East. This is clearly inflationary for the entire world, except possibly for China which has locked in its prices for Russian exports. And there would not be much help from the strategic petroleum reserve since we already tapped much of it when prices rose two years ago. Note that demand for oil is recently rising in concert with historical trends going into the summer which should keep demand strong. (H/T my friend Bill Hamlin, oil trader and New Hampshire Congressional candidate.)

Source: Bill Hamlin

Goods prices are indeed falling. Except…

President Biden decided last week to add new 20‒100%+ tariffs on certain Chinese goods such as electric vehicles. Trump says he will add even broader tariffs if he wins, and not just on China. As my friend David Kotok wrote this week (we sent the entire piece to Over My Shoulder readers, by the way):

- Import tariffs trigger price increases, adding to inflation pressure though estimating the numbers is difficult.

- Tariffs operate much like a national sales tax, collected by US businesses and remitted to the Treasury.

- While tariffs may create or maintain US jobs, they definitely raise costs, which is inflationary.

- Meanwhile, US jobs continue to be exported as technology enables lower-paid foreign workers to serve US customers.

I have been opposed to tariffs in general for decades. On the rare occasions they are necessary, they should be carefully targeted and used mainly for legitimate national security challenges.

Tariff impact might be a small number in terms of total inflation, but it will add to inflation pressure and encourage the Federal Reserve to keep rates higher for longer.

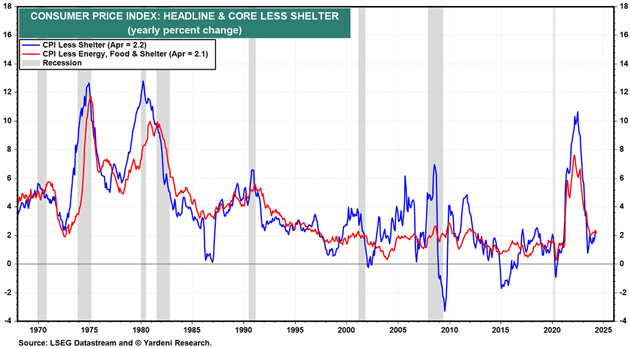

Then again, Dr. Ed Yardeni at the conference and then later this week said he believes that inflation will fall. Quoting:

(1) The headline and core CPI excluding shelter were up 2.2% and 2.1% y/y last month (chart). This suggests that the PCED inflation rate is on track to fall to the Fed's 2.0% target by the end of this year, as long as rent inflation continues to moderate.

Source: Yardeni Research

(2) Both rent of primary residence and owner’s equivalent rent continued to disinflate in April (chart).

Source: Yardeni Research

A final sidebar. The Japanese yen is at 155 as I write. The Chinese yuan is basically down 8% over the last two years against the dollar. The yen is down over 20% and still falling. This coupled with tariffs will put more pressure on China. Why buy from China when you can buy many of the same things from Japan with better legal terms and easier business conditions? And no tariffs?

Will the Bank of Japan let the yen go to 160‒170 without intervening? They have the dollar reserves to rip the face off the yen shorts IF they want to. They will certainly talk like they do, but an organically weaker yen will boost Japanese exports and nominal profits. The BOJ works in mysterious ways.

A falling yen puts pressure on China. When it begins to bite into their exports, Beijing will almost be forced to let their currency devalue. (H/T Lance Gatling.)

Shades of the 1930s and Smoot Hawley tariffs. This is no bueno.

Cape Town, Dallas(?), and the Caribbean

The original plan was for Shane and I to go to Cape Town for a few days and then visit Europe for a week or so on the way back. The additional airfare would have been no problem in the past. Now, however, the cost to get to South Africa semi-first class is staggeringly high, especially for a few days, so Shane is going to stay home, avoid major jet lag, and we will see some of the smaller Caribbean islands this summer. I might go to Dallas in mid-June.

A friend is coming to Puerto Rico and an economy class ticket on American is over $1,000, even a week in advance. A few years ago, it was $300-400. Can you spell inflation, boys and girls? Local food prices are breathtaking, both at the grocery store and in restaurants. While inflation for me is now mostly annoying in terms of lifestyle, it simply offends my country boy roots.

My experience from the 1970s says it can get worse if we don’t get inflation under control. And with that happy thought, it is time to hit the send button. Thank goodness there’s no inflation on friends and family relationships. So enjoy the simple pleasures. And don’t forget to follow me on X!

Your having to run faster to stay in place analyst,

|

|

John Mauldin |