In 2017 Germany brought home nearly $31 billion of gold bars that had been stored in New York and Paris after World War II. The Financial Times gives a good account of how Germany amassed, lost, and then got its gold back.

Perhaps no other country (except maybe Zimbabwe) understands the value of bullion as a store of value than Germany. Hyperinflation during the Weimar Republic of the 1920s had citizens piling near-worthless Deutsche marks into wheelbarrows just to buy bare necessities. During the Second World War Nazi Germany looted about 4 tonnes of gold and stored it in the Reichsbank. But in 1948 the Allies recovered it and gave it back to its rightful owners, leaving Germany’s bullion vaults bare.

It wasn’t long however until Germany was again in a position to buy gold. The Wirtschafswunder — the economic miracle — of the 1950s and ‘60s allowed West Germany to stockpile large amounts of gold. Under the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, Germany could use dollars, earned by successful export businesses that traded them in for marks, to buy gold at $35 an ounce.

The country managed to accumulate over 1,500 tonnes in the decades that followed. However this gold was not considered safe, with the Bundesbank in Frankfurt only about 100 km from Soviet-controlled East Germany, as told by the FT. It therefore made sense to store its gold in Paris, London, or New York. After the fall of communism in 1991, that rationale disappeared.

In 2019, other countries in Europe wanted their gold back.

Amid global trade uncertainty, a pall hanging over the European Union due to continued economic weakness and the pending exit of Great Britain, and dark, nationalist undercurrents swirling, several of the 28-strong EU members looked to gold as collateral.

Slovakia and Poland became the first European Union countries since Germany to call for a repatriation of their gold, which had been stored in Bank of England vaults for decades. Gold reserves owned by Poland and a number of other East European nations were spirited off to London at the outbreak of World War II, amid fears they would fall into the hands of Nazis.

The prime minister of Slovakia called on the country’s parliament to repatriate its gold from the UK because it couldn’t be trusted with the precious metal.

“You can hardly trust even the closest allies after the Munich Agreement,” said Robert Fico, leader of the socially conservative Smer Party. “I guarantee that if something happens, we won’t see a single gram of this gold. Let’s do it as quickly as possible.”

The Munich Agreement was the 1938 pact between the UK, France, Italy, and Germany that permitted Adolf Hitler to annex part of Czechoslovakia.

Fico’s comments were uttered the same week as Poland repatriated 8,000 gold bars worth £4 billion (USD$5.25 billion) from London to Warsaw, in a top-secret operation involving planes, helicopters, high-tech trucks, and specialist police, The Daily Mail reported. Eight night-time flights were made from an undisclosed London airport over the course of several months, shifting the bullion take weighing 100 tons, to un-named locations in Poland.

According to the head of Poland’s central bank, “The gold symbolizes the strength of the country.” Governor Adam Glapinski said at least half of Poland’s 228.6 tonnes would be held in the National Bank of Poland (NBP), with the other half to remain in the UK.

Poland bulked up on its gold from 2017-19, buying 125 tonnes. In its July 2019 announcement, the NBP called gold the “most reserve” of all reserve assets and an “anchor of trust” that diversifies political risk.

At the end of August 2024, the National Bank of Poland had about 363 tons worth over €29 billion. Gold now constitutes 14.7% of Poland’s foreign currency reserves.

Hungary had no gold at the end of 2016, but in 2019 Hungary brought back all of its gold reserves from the Bank of England for the first time in 31 years, while at the same time announcing that it had increased its gold holdings by 1,000% (10-fold) from 3.1 to 31.5 tonnes.

Hungary had no gold at the end of 2016, but in 2019 Hungary brought back all of its gold reserves from the Bank of England for the first time in 31 years, while at the same time announcing that it had increased its gold holdings by 1,000% (10-fold) from 3.1 to 31.5 tonnes.

Hungarian gold reserves reached an all-time high of 94 tonnes in the first quarter of 2021, a number that remained static as of the first quarter of 2024, says the World Gold Council, via Trading Economics.

Romania voted in April 2019 to repatriate the country’s gold reserves; about 60% of its 103.7 tonnes were stored at the Bank of England. The new law stipulated that only 5% of its gold could be kept abroad.

In November 2019 Serbia made a 9-tonne bullion buy, prompting its central bank governor, Jorgovanka Tabakovic, to say, “We have completed gold purchase transactions and Serbia is safer today with 30.4 tons of gold worth around 1.3 billion euros ($1.4 billion).”

Gold reserves in Serbia hit an all-time high of 40.67 tonnes in the first quarter of 2024, a smidgen higher than the 39.95t in the fourth quarter of 2023.

Among other European nations that wanted to repatriate their gold from the Bank of England and the New York Fed, were the central banks of Austria, Turkey, the Netherlands, and the Czech Republic.

So why did Eastern Europe want its gold back?

A 2019 Bloomberg article points to Hungary’s anti-immigrant Prime Minister Victor Orban ramping up holdings of gold to boost the security of his reserves, Robert Fico bringing up the detested Munich Agreement, which sold out then-Czechoslovakia to Hitler’s Nazis, as a reason for repatriating its gold, and Poland’s wish to strengthen, via gold purchases, its half-a-billion-dollar economy, as examples of decisions to buy gold being motivated by fear, and some might say, hatred of outsiders.

Gold Telegraph points out another reason why countries were, and are, wanting to bring their gold home from the US:

It’s not a secret that there is a lack of confidence with regard to the U.S. Treasury’s claim that it currently holds 261,000,000 ounces of gold in Fort Knox and other locations. On top of that, the official gold reserves have never gone through a thorough independent audit.

Which you would think makes lots of countries feel quite uneasy with regards to their gold holdings.

In the above-mentioned cases of repatriation, the banks holding other countries’ gold had no problem returning it. Not so when the president of Venezuela, Nicolas Maduro, asked the Bank of England to return Venezuela’s substantial gold reserves to help deal with the country’s economic crisis.

The trouble was, that doing that would violate international sanctions against Venezuela. The sanctions were an attempt to cut Maduro off from his assets and steer them toward the country’s opposition leader, Juan Guaido, who claimed the presidency.

So in January 2019, the Bank of England refused Maduro’s request to repatriate a billion dollars worth of gold, a significant chunk of its $8 billion in foreign reserves.

Maduro later did an end-run around the sanctions by loading 7.4 tons of gold worth $300 million from its central bank onto Russian planes, which flew to Uganda for liquidation into cash.

A Wall Street Journal investigation revealed how the scheme worked: once the gold arrived at the airport in Entebbe, it would pass through a legitimate gold refinery, which would then sell it to companies in the Middle East.

Maduro’s lucrative black market gold trade allowed him to maintain control of his regime, and keep his military loyal to him, by selling an estimated 73.3 tons of bullion valued at around $3 billion to companies in the Middle East and Turkey between 2017 and February 2019.

De-dollarization

Protecting against sanctions became important again in early 2022 when Russia marched into Ukraine. This event is largely responsible for the current wave of de-dollarization, the act of buying gold and other currencies as a way of diversifying from the mighty US dollar and US Treasuries.

Central banks purchase Treasuries to bulk up their foreign exchange reserves. They do this especially during periods of unrest, or when the economic forecast is bleak. Gold’s role as a safe haven is well-documented. Of course, Treasuries are as much sought-after by investors in a crisis.

De-dollarization by countries at odds with the United States, who fear that the US could freeze their dollar assets like Washington did to Russia following the invasion of Ukraine, is increasing the appeal of gold as a foreign exchange alternative.

Many emerging-market economies are buying gold because they don’t want to be stuck in the same situation as Russia, which had about half of its $640 billion of forex reserves frozen by the US and its allies.

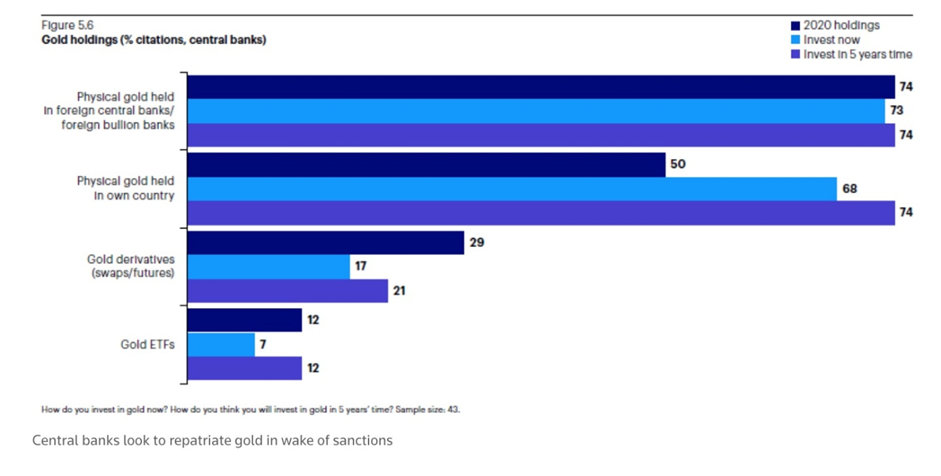

A 2023 survey by Investco found that an increasing number of countries are repatriating their gold reserves as protection against sanctions.

Almost 60% of respondents — from a total of 85 sovereign wealth funds and 57 central banks that took part in the annual Invesco Global Sovereign Asset Management Study — said that seeing Russia’s assets frozen made gold more attractive, while 68% were keeping reserves at home compared to 50% in 2020.

Geopolitical concerns, combined with opportunities in emerging markets, are also encouraging some central banks to diversify away from the dollar, Reuters said.

I agree that diversification is central banks’ main motivation behind gold purchases, which hit a record in 2022. It’s not so much that developed countries are dumping dollars; rather, they are buying gold and other countries’ currencies. In developing nations, there is a definite move away from the dollar but the amounts are so small as to not really make a difference in global Treasury holdings. Arguably, the US dollar is not going anywhere as the world’s reserve currency.

Gold gets Tier 1 status

Basel I, II, and III were a response to the 2008 financial crisis. The regulations require banks to maintain proper leverage ratios and to meet certain minimal capital requirements.

Sprout-less Gold now Tier 1 Capital

Under the old Basel I and II rules, gold was rated a Tier 3 asset. Under Basel III Tier 3 has been abolished. As of March 29, 2019, gold bullion is a Tier 1 asset. Also, and this is important, under Basel III a bank’s Tier 1 assets have to rise from the current 4% of total assets to 6%.

“Tier 1 capital is the core measure of a bank’s financial strength from a regulator’s point of view. It is composed of core capital which consists primarily of common stock and disclosed reserves (or retained earnings) but may also include non-redeemable non-cumulative preferred stock. Banks have also used innovative instruments over the years to generate Tier 1 capital; these are subject to stringent conditions and are limited to a maximum of 15% of total Tier 1 capital.” — Wikipedia

The Basel Committee for Bank Supervision (BCBS), the maker of global capital requirements and whose Basel III rules form the basis for global bank regulation, made gold a bank capital Tier 1 asset.

“Gold has historically been classified as a Tier 3 asset. When determining how much money a bank can loan, the bank’s gold holdings have traditionally been discounted 50 percent of the current market value. With value cut in half, banks have little incentive to hold gold as an asset.” — Frank Holmes, usfunds.com

The BCBS is a committee of banking supervisory authorities established by the central bank governors of the Group of Ten countries in 1974. The committee’s members currently come from Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, Hong Kong SAR, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Because gold is a Tier 1 Capital asset, banks can operate with far less equity capital than is normally required. Gold is the new backstop for debt, currencies, and bank equity capital.

“Anyone who understands gold’s historic role will grasp the importance of the argument behind extra bank leverage. Direct ownership of bullion by a bank is superior to holding the fiat money issued by a central bank. It should increase confidence in any bank and the system as a whole. Given relative values, bank purchases of bullion will drive the value of gold as Tier 1 capital up relative to other qualifying assets, increasing its desirability for regulatory purposes further without a gold-owning bank doing anything.” — Alasdair Macleod, resourceinvestor.com

Andy Schectman, president and owner of Miles Franklin Precious Metals, believes that when the BIS made gold a Tier 1 asset, it accelerated the de-dollarization and repatriation trends.

Nowadays, repatriation is being performed not so much by European countries as those in the Middle East, Africa, and wanna-be members of the BRICS — Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

In an interview with Kitco News, Schectman points out the Reserve Bank of India purchased 1.5 times the amount of gold they bought last year just in the first four months of this year. More importantly, though, the Indian central bank moved 100 tonnes of gold stored in the Bank of England since 1991 back to the RBI. And it’s not just India.

“We’ve seen Saudi, Arabia, Egypt, and half a dozen African countries just bring all of their gold back from the New York Fed,” he said.

“So not only is gold a Tier 1 asset, a riskless asset. If it’s a riskless asset you want to remove counterparty liability so these countries who understand that it can replace the dollar, or rather the bond market, the Treasury in terms of its status as a reserve and being recognized by the BIS, they’re also removing counterparty risk by taking it back from the Bank of England, which is the same thing as the London Bullion Market Association and the Comex, which is the New York Fed. This repatriation is just as important as the accumulation,” said Schectman.

BRICS+

The trend is gathering pace, as the number of countries joining the BRICS increases. Take the following number with a grain of salt considering the source, but according to Vladimir Putin, who currently chairs the intergovernmental organization, as many as 34 countries have expressed a desire to participate in BRICS.

Following its launch in 2009, BRICS has expanded to 11 members with the addition of Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

BRICS+ members now account for 45% of the world’s population, 25% of global trade, and 31.5% of global GDP, Kitco writes:

The expanding list of prospective members underscores the growing strength of the bloc, which is quickly moving to de-dollarize and focus on their local currencies to help grow their economies.

“Amid focused debates and high optimism to establish an economic clout, BRICS, together with new members and its partners (outreach format) are steadily looking forward to a new era of de-dollarizing the global economic system by introducing a new currency and also to set up a new payment system, most likely, during the forthcoming October 2024 summit in Kazan, the Republic of Tatarstan,” wrote Kester Kenn Klomegah, an independent researcher and writer on African affairs in the Eurasian region and former Soviet republics.

“In pursuit of defining the collective determination to achieve these economic policy goals, BRICS has over the months been deliberating broadly the effectiveness and the importance of its newly-designed mechanisms and a well-balanced approach for reconstructing the western-dominated dollar-system in the world,” he added.

It’s not only the addition of new members to BRICS that is presenting a challenge to the current international economic order.

China is in competition with the United States to replace the dollar with the yuan, while China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System and Russia’s System for Transfer of Financial Messages are challenging the global economic order led by the United States and the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications, or SWIFT.

Schectman notes that over the past year, Saudi Arabia has been selling oil to China for yuan, which is convertible to gold on the Shanghai Gold Exchange. “We’re seeing an extraordinary amount of action coming off the Shanghai Gold Exchange,” he told Kitco News.

Another example is Iran, which in 2023 struck a deal with China to modernize its biggest airport, paid for with oil rather than US dollars.

Saudi Arabia is now a member of Project mBridge, a cross-border digital payments system that is a collaboration between the BIS Innovation Hub Hong Kong Centre, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, the Bank of Thailand, the Digital Currency Institute of the People’s Bank of China and the Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates.

The mBridge Ledger serves as a platform for implementing multi-currency, cross-border payments in central bank digital currencies.

Schectman notes mBridge did two trial trades in 2023: first, China using digital yuan to buy oil from the United Arab Emirates; and second, trading cross-border digital yuan for gold.

“When you take a look at what gold represents and the massive amount of gold accumulation by the southern hemisphere and the drawdown in all of the world’s exchanges and the convertibility of gold off the Shanghai Gold Exchange for yuan, all of these things are coming together where I think it’s setting up for a perfect storm…,” he said. “This is about commodities leading the way and these countries are in a race to slowly, methodically accumulate commodities without causing too much attention.

He gave the example of China selling Treasuries, where its $3 trillion accumulation of T-bills has been whittled down to $700 billion, while their gold holdings grew for 19 straight months.

“That’s indicative of all of these countries in the southern hemisphere, they are slowly and methodically de-treasuring and accumulating gold.”

Another tool for de-dollarizing is the BRICS Bridge, introduced in July. As Kitco reported,

BRICS Bridge is to give developing countries, especially in the Global South, the ability to limit or restrict their dependence on the U.S. dollar by promoting their own national currencies for trade settlements.

Central Bank gold buying

Meanwhile, central banks continue to accumulate gold at record levels.

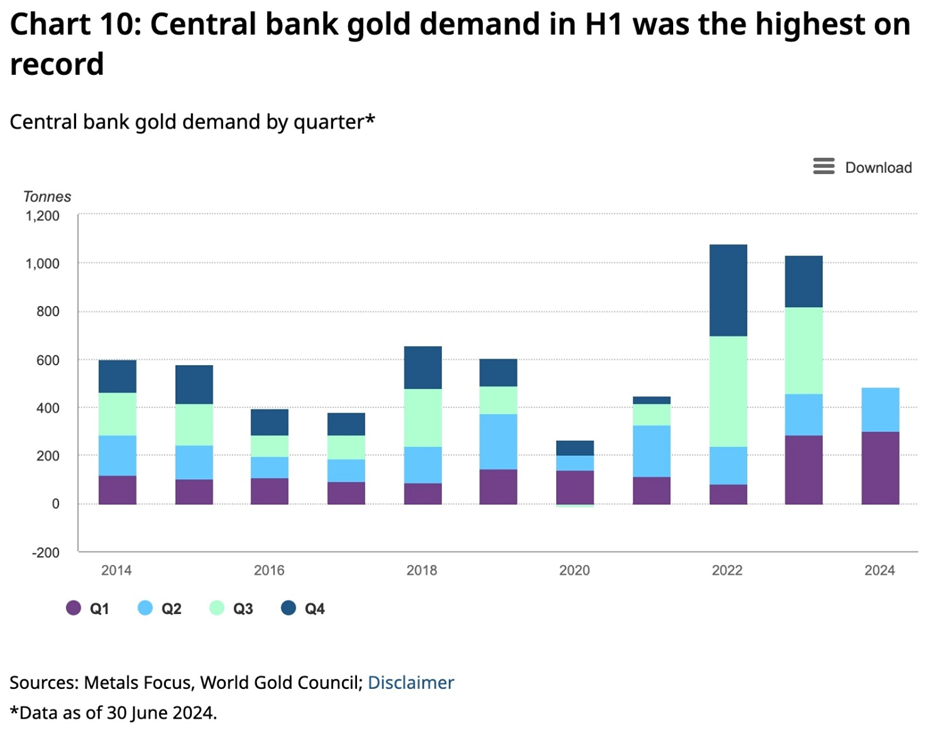

According to the World Gold Council, central bank demand totaled 229 tonnes in the fourth quarter of 2023, lifting CB net purchases to 1,037 tonnes, just off the record set in 2022 of 1,082t.

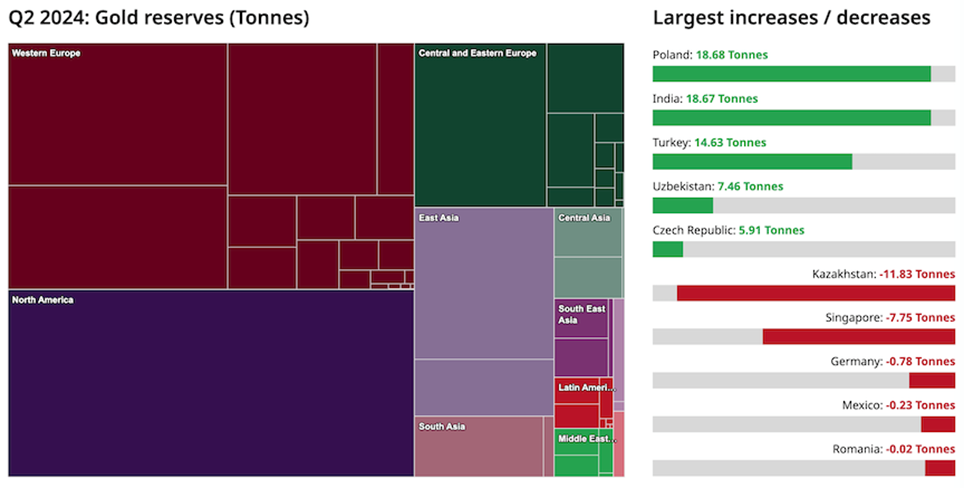

Last year China and Poland added the most to global official gold reserves, which are now estimated to total 36,7000 tonnes.

More than a quarter of the more than 7,800 tonnes accumulated since 2010 have been in the last two years, states WGC.

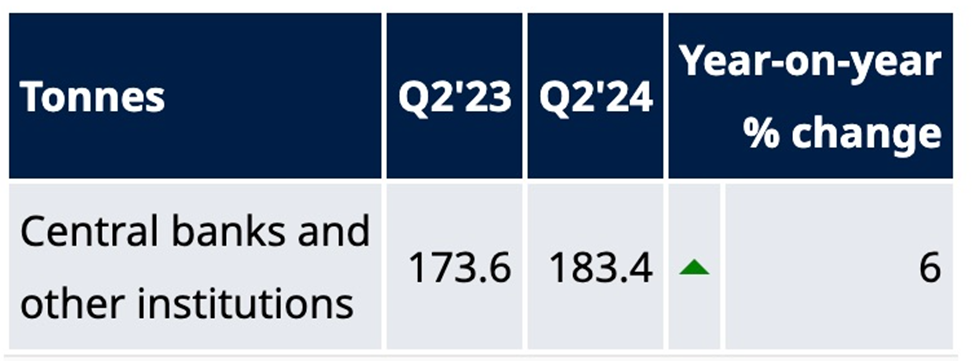

Central bank gold buying in the first half of 2024 was the highest on record, with net purchases of 483 tonnes 5% above the previous record of 460 tonnes set in H1 2023. Q2 year on year was 6% higher.

During Q2, both the Reserve Bank of India and the Central Bank of Nigeria repatriated gold from the UK and US respectively.

Proving our thesis of gold-buying and repatriation moving from north to south, the World Gold Council says Activity remained firmly driven by emerging markets (EM), with the latest quarter seeing 14 EM central banks increasing or decreasing their gold reserves by a tonne or more. By comparison, only a single developed market central bank [Singapore] added gold during Q2.

The central banks of Turkey, Czechia, Qatar, Russia, Iraq, Jordan, and the Kyrgyz Republic were the other buyers of note.

While China slowed down its gold-buying during the second quarter, between November 2022 and April 2024, the People’s Bank of China reported purchases of 316t, taking its gold reserves to 2,264t. Gold now accounts for 5% of the PBC’s total reserves, the highest share since 1996.

According to the WGC’s central bank survey, 81% of respondents said they expect global central bank holding to increase in the next 12 months, with 29% expecting their own bank’s gold reserves to rise.

The survey also highlighted the top reasons for central banks to own gold coalesce around safety:

Respondents indicated that its role as a long-term store of value/inflation hedge, performance during times of crisis, effectiveness as a portfolio diversifier, and lack of default risk remain key to gold’s allure.

As of Q2, the United States owned the most gold at 8,133 tonnes, followed by Germany, Italy, Russia, China, Japan and India. It’s interesting to note that for the United States, Germany, France, Portugal, and Uzbekistan, gold represents 70% or more of the country’s foreign exchange reserves.

Conclusion

The days of a central bank allowing another central bank to hold its gold reserves are likely over. Between de-globalization, toxic nationalism in Europe, and the threat of the United States confiscating a country’s foreign exchange reserves, has fostered a movement of “bringing the gold home”.

Gold repatriation started in Europe but it has migrated to India, the Middle East, and Africa. Gold-buying and gold repatriation are tied to the de-dollarization agenda of the ever-expanding BRICS+ group of countries, that want to use their own currencies to grow their economies.

Russia and China already have systems in place to circumvent SWIFT. BRICS Bridge and Project mBridge are the latest payment settlement mechanisms.

Central bank buying was to a large extent responsible for the run-up in the gold price over the past year, despite the headwinds of high bond yields and a strong US dollar. Safe-haven buying played a part too.

Central banks and we at AOTH know that gold is the only store of value that can be counted on in a time of crisis when everything else – i.e. fiat money – fails.

Richard (Rick) Mills