December 7, 1941 will forever be remembered as, in the words of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, "a date that will live in infamy." Another infamous date is April 5, 1933—the day that FDR ordered the seizure of the private gold holdings of the American people.

By attacking innocent citizens, Roosevelt bombed the country's gold standard just as surely as Japan bombed Pearl Harbor.

On this 90th anniversary of the seizure, it behooves us to recall the details of it, for multiple reasons: It ranks as one of the most notorious abuses of power in a decade when there were almost too many to count.

It's an example of bad policy imposed on the guiltless by the government that created the conditions it used to justify it. And the very fact of compliance, however minimal, is a scary testimony to how fragile freedom is in the middle of a crisis.

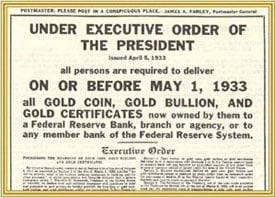

Suddenly on April 5, 1933, FDR told Americans—in the form of Executive Order 6102—that they had less than a month to hand over their gold coins, bullion and gold certificates or face up to ten years in prison or a fine of $10,000, or both.

After May 1, private ownership and possession of these things would be as illegal as Demon Rum. After Prohibition was repealed later the same year, the sober man with gold in his pocket was the criminal while the staggering drunk was no more than a nuisance.

Hoarding gold was preventing recovery from the Great Depression, FDR declared. Government (which caused the Depression in the first place) had no choice, if you can follow the logic, but to seize the gold and do the hoarding itself.

But of course, the big difference was this: In the hands of the government, huge new gold supplies could be used by the Federal Reserve as the basis for expanding the paper money supply. The President who had promised a 25 percent reduction in federal spending during his 1932 campaign, could now double spending in his first term.

What evidence suggested Americans were "hoarding" gold? Roosevelt pointed to a run on banks that immediately preceded his April 5 seizure decree. Indeed, people were showing up at tellers' windows with paper dollars demanding the gold that the paper notes promised. But Roosevelt had prompted the bank run himself!

On March 8, three days after succeeding Herbert Hoover as the new President, FDR declared the gold standard to be safe. After all, America's gold reserves were the largest in the world.

Then out of the blue, on March 11, the President issued an executive order preventing banks from making gold payments. The message was clear: In spite of its campaign pledge to protect the integrity of the currency, this was an administration intent on spending and printing like none before. Citizens who wanted to protect their savings and financial assets suddenly had every good reason to find and keep whatever gold they could get their hands on.

James Bovard writes in "The Great Gold Robbery,"

Roosevelt was hailed as a visionary and a savior for his repudiation of the government's gold commitment. Citizens who distrusted the government's currency management or integrity were branded as social enemies, and their gold was seized. And for what? So that the government could betray its promises and capture all the profit itself from the devaluation it planned.

Shortly after Roosevelt banned private ownership of gold, he announced a devaluation of 59 percent in the gold value of the dollar. In other words, after Roosevelt seized the citizenry's gold, he proclaimed that the gold would henceforth be of much greater value in dollar terms.

Dentists, jewelers, and industrial users were allowed to acquire gold to meet their "reasonable needs." If you had a gold tooth, the government did not yank it out. But if you possessed more than $100 in monetary gold (coin or notes denominated in the yellow metal) after May 1, 1933, you were a villainous lawbreaker until private gold ownership was legalized four decades later.

With the passage of the Thomas Amendment to an agricultural bill on May 12, 1933, vast new presidential powers over money were affirmed by Congress. But even some of FDR's own party still had a conscience. Democratic Senator Carter Glass of Virginia solemnly and honestly lamented,

It's dishonor, sir. This great government, strong in gold, is breaking its promises to pay gold to widows and orphans to whom it has sold government bonds with a pledge to pay gold coin of the present standard of value. It is breaking its promise to redeem its paper money in gold coin of the present standard of value. It's dishonor, sir.

When FDR followed up in June by abrogating the gold clauses in both private and government contracts, he asked blind Oklahoma Senator Thomas Gore, a fellow Democrat, for his opinion. Gore had lost his eyesight at the age of 12 but he saw right through FDR on this matter. He famously replied, "Why that's just plain stealing, isn't it, Mr. President?"

In his book, Economics and the Public Welfare, A Financial and Economic History of the United States, 1914-1946, the great economist Benjamin Anderson recalled Senator Gore's words on the Senate floor:

Henry VIII approached total depravity, as nearly as the imperfections of human nature would allow. But the vilest thing that Henry ever did was to debase the coin of the realm. [See: "How Henry VIII Debauched English Money to Feed His Lavish Lifestyle."

Many Americans were cowed by government threats to do the "patriotic" thing and turn in their gold as Roosevelt mandated. But true to the rugged individualism and defiance of tyranny ingrained in our culture, FDR's order prompted widespread noncompliance. Best estimates, suggest that for every one dollar in gold that Americans relinquished, they quietly kept three.

If the federal government tried today to seize the gold holdings of private American citizens, how much do you think we would turn over?

Call me a scofflaw if you want, but it would NOT get its hands on mine.

This article was authored by Larry Reed and originally appeared at the Foundation for Economic Education.