In a recent interview, the Dutch central bank (DNB) shares it has equalized its gold reserves, relative to GDP, to other countries in the eurozone and outside of Europe. This has been a political decision. If there is a financial crisis the gold price will skyrocket, and official gold reserves can be used to underpin a new gold standard, according to DNB. These statements confirm what I have been writing for the past years about central banks having prepared for a new international gold standard.

Wouldn’t a central bank that has one primary objective—maintaining price stability—serve its mandate best by communicating the currency it issues can be relied upon in all circumstances? By saying gold will be the safe haven of choice during a financial collapse, DNB confesses its own currency (the euro) does not weather all storms. Indirectly, DNB encourages people to own gold to be protected from financial shocks, making the transition towards a gold-based monetary system more likely.

Old gold vault of DNB in Amsterdam.

How to Prepare for a Gold Standard

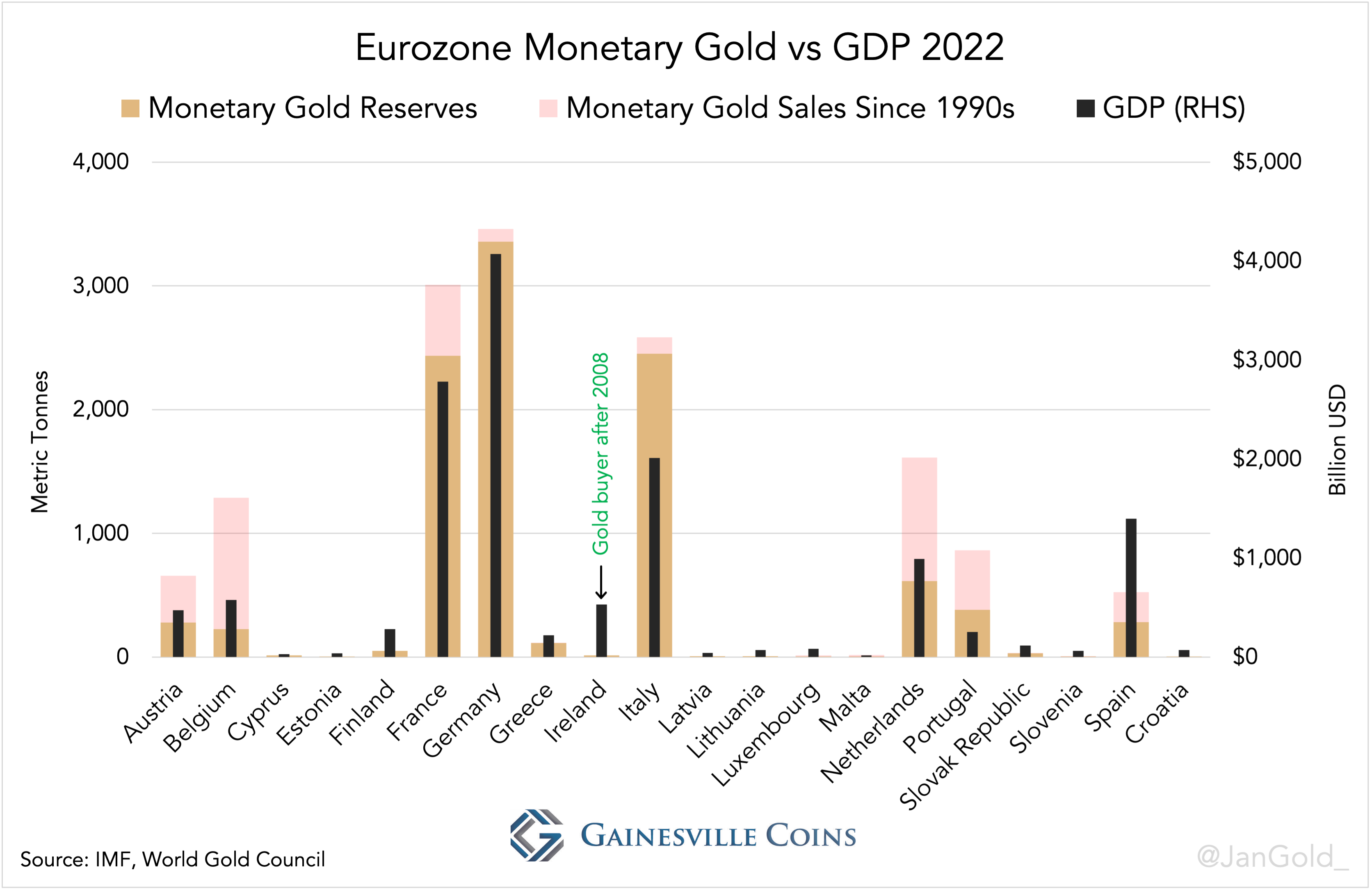

In my latest article on this subject—“Europe Has Been Preparing a Global Gold Standard Since the 1970s. Part 2”—I have demonstrated that central banks of medium and large economies in the eurozone have balanced their official gold reserves, proportionally to GDP, to prepare for a gold standard (/gold price targeting system). My analysis was pieced together by scarce quotes from central banks and data of European gold and foreign exchange holdings. My conclusion was that several medium-size economies in Europe (the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, and Portugal) sold large amounts of gold from the early 1990s to 2008 to come on par with France, Germany, and Italy. I wrote:

Seemingly there are guidelines in the eurozone for national central banks to hold an appropriate amount of gold relative to GDP.

In another article, I revealed that in the early 1990s the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) was buying the gold DNB was selling. By selling gold Europe was allowing developing countries to buy gold and come on par with the West. China too has expressed its desire to bring its gold holdings more in line with the size of its economy, just like the Europeans, and thus to international averages. From Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad in 1993:

China announced that it is working to build up its [gold] reserves in order to bring it more in line with the size of Chinese GDP.

The above, and DNB’s most recent confirmation of leveling reserves, implies there are international agreements on the distribution of gold holdings.

Evenly spread gold reserves internationally are a prerequisite for a smooth transition to a gold standard. If some countries own too much and others too little, as was the case in the 1970s, a newly implemented gold standard would prove to be deflationary because the ones with too little gold would have to buy in, pushing up the real price of gold. As long as official gold reserves are evenly spread the nominal gold price can be increased to what is suited for all countries, before introducing a new system.

Another sign of Europe having prepared for a new gold arrangement are the repatriations by several countries. In the eurozone Germany, the Netherlands, France, and Austria repatriated (and redistributed) bullion for security reasons, while keeping a substantial share of their assets in liquid markets such as London. Additionally, Germany, France, and Sweden, that we know of, have upgraded gold bars that didn’t adhere to current wholesale industry standards so now all their metal can be traded instantly.

Last but not least, European central banks’ communication about gold has become unequivocally clear and candid. Stating “gold is the bedrock of stability for the international monetary system” (Germany), “gold is an excellent hedge against adversity” (Italy), “gold is … considered to be the ultimate store of value” (France), and gold “may play a stabilising role … in times of structural changes in the international financial system or deep geopolitical crises” (Hungary). Remarkable statements from entities tasked with guaranteeing financial stability.

Dutch Central Bank Comes Clean on Gold Strategy

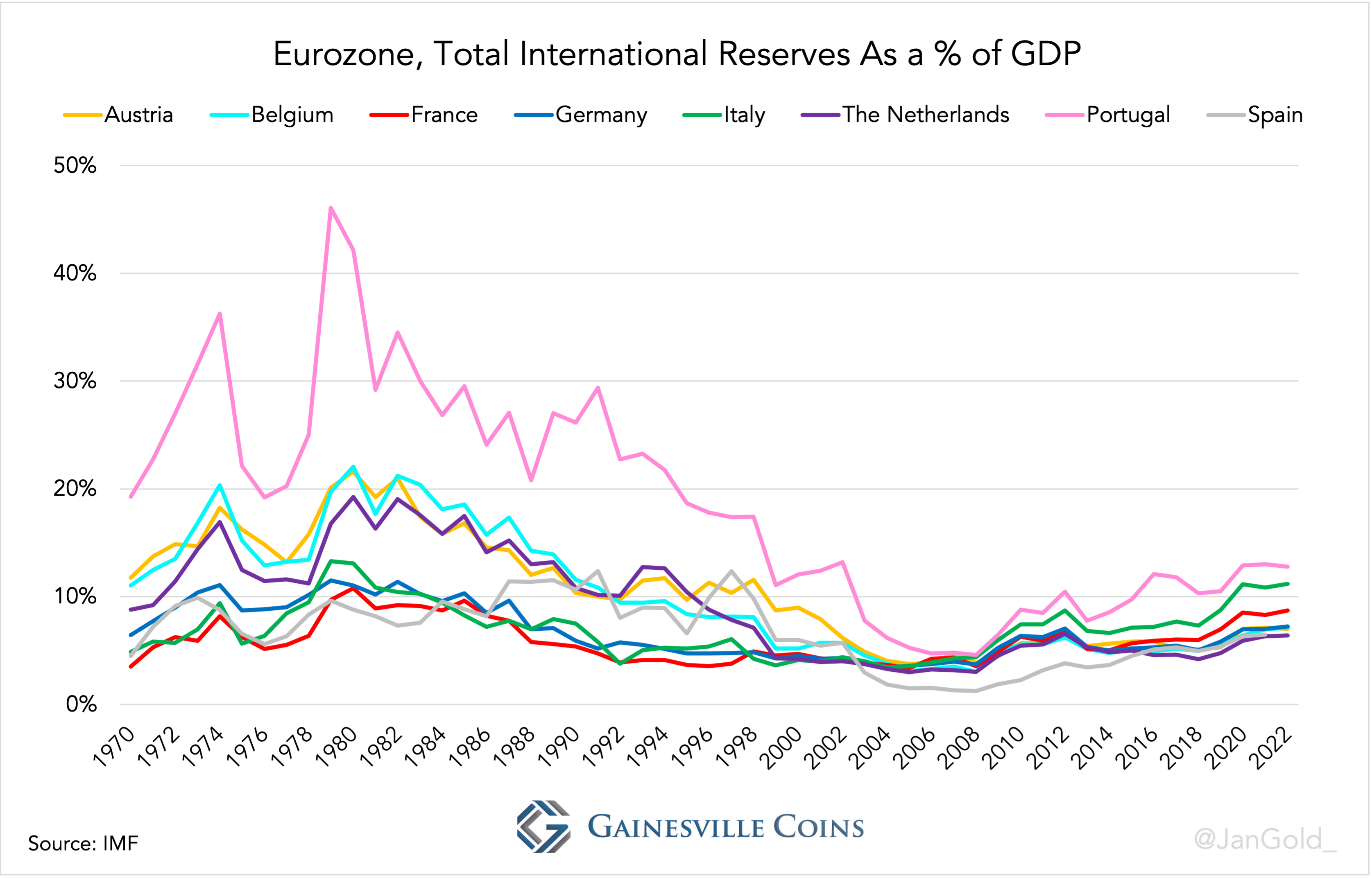

When I asked European central banks about a legal requirement to equalize their gold reserves, two of them replied there is no such obligation. Which is strange given the obvious aligning of reserves over the past decades, illustrated in the charts below, and the new comments by DNB.

International gold reserves as a percentage of GDP in the eurozone, 1970–date.

Monetary gold reserves and gold sales relative to GDP in the eurozone.

DNB provides an explanation in the aforementioned interview by revealing that their gold policy is set in consultation with its shareholder, the Ministry of Finance of the Netherlands. The idea of balancing gold reserves was first conceived in the 1970s and then executed from the early 1990s until 2008. With no legal requirements for European central banks to balance reserves, the seeds of their actions could be found at their respective governments.

My Freedom of Information (FOI) requests about this subject submitted at DNB have never yielded results because DNB is exempt from such inquiries. This week I have sent FOIs to the Dutch Ministry of Finance to find out what gold policy agreements governments have made internationally. To be continued.

Interview Transcript

The interview with Aerdt Houben, Director of Financial Markets for DNB, was conducted by Anna Dijkman from Het Financieele Dagblad. The following is a translation of the most important part of the conversation (in the first segment we hear Dijkman make a few comments for the listener in between Houben’s talk):

HOUBEN: 612 tonnes of gold. That's our total holdings. It's worth about €35 billion euros at the moment and we have diversified it around the world, as a good investor should. We've spread it over four locations, with about 30% in the Netherlands, just over 30% in New York at the Federal Reserve, over 20% in Canada and 18% in London.

The gold really goes way back. At the end of the nineteenth century DNB started accumulating gold, which was important to establish confidence in our currency.

DIJKMAN (narrator): The Netherlands was on the gold standard at that time. That means money was backed by gold at the central bank. People could always exchange their banknotes for gold. That lasted until 1936. After World War II, another monetary system based on gold was introduced: Bretton Woods. More than 40 countries agreed with each other that their currencies had a fixed exchange rate against the dollar. The dollar, in turn, could be exchanged for gold at a fixed price.

HOUBEN: The Dutch guilder was actually stable to gold via the dollar. We received dollars when we had surpluses and we lost dollars when we had deficits. And the dollars were redeemable in gold.

DIJKMAN (narrator): Those surpluses and deficits Houben talks about have to do with international trade. The Netherlands, as well as other countries, exported more than it imported and therefore we had a surplus.

HOUBEN: As a result of the surplus our gold reserves increased, or we got more dollars that we converted into gold. We kept asking the Americans, can you convert our dollars into gold? We became owners of gold that was at the Federal Reserve in New York, and it's still there.

The Americans made losses from their trade relationships. Eventually it was unsustainable for them to lose more and more gold reserves. In 1971, President Nixon announced America's departure from Bretton Woods. But by then we had over 1,700 tonnes of gold. Yes, we did very well then.

DIJKMAN (narrator): Since the 1970s, gold had no role in the monetary system. But we and other countries had substantial reserves.

HOUBEN: The beauty of gold is that it’s stable in value, it retains its value. That's one of the reasons why central banks hold gold. Gold has intrinsic value unlike a dollar or any other currency, let alone Bitcoin. Gold has value on its own. It’s a fungible product. It's a liquid product, you can buy and sell it almost anywhere in the world. So, it’s really an outstanding commodity to base an exchange rate system [gold standard] on.

DIJKMAN: Yet we sold quite a bit of our gold starting in the 1990s. Why?

HOUBEN: Well, I think once you let go of tying your exchange rate to gold, then one of the main reasons for holding that gold is gone. Then you might ask, why are we still holding that gold? Why gold and not a portfolio of stocks or bonds or something else? There are a number of things that make gold very attractive to central banks. Gold is like solidified confidence for the central bank. It's something that has historically fulfilled that role. If we ever unexpectedly have to create a new currency or a systemic risk arises, the public can have confidence in DNB because whatever money we issue, we can back it with the same value in gold [gold standard].

In the 1970s, and we did that exercise again in the 1980s and 1990s, we looked at how much gold we have and whether that was still in proportion. It's a kind of an insurance against systemic risk, and the question was to what extent should we continue to insure against this kind of systemic risk? And then we looked at what globally, what other major central banks were doing. We concluded that we owned too much gold. Our stock of gold was then reduced to about the average of the larger gold holding countries in Europe.

DIJKMAN: We do still rank in the top ten, I think globally.

HOUBEN: We are number seven. Yes, in terms of our GDP. Yes, that's a fine position.

DIJKMAN: So how do you determine what is an appropriate amount then? Because that €35 billion, that doesn't quite relate to our GDP, does it?

HOUBEN: We have about 4% of our GDP in our gold reserves. And that's comparable to France, Germany, and Italy.

DIJKMAN: Is that the rule of thumb roughly?

HOUBEN: I think to be very honest there is no optimum, so you can't determine objectively what is the optimal level of gold reserves. Just like with insurance, because you don't know when and to what extent a fire is going to occur, and so on. Of course, it also has to do with the shocks of the future, with all kinds of uncertain factors. I think it’s just that we as Dutch people want to be a little bit careful. We think it's good to have a certain basis of solvency at the central bank invested in gold.

DIJKMAN: Because you could also say if it's a kind of insurance, for example if the financial system collapses or whatever, shouldn't you have a lot more?

HOUBEN: You could think that. I think it's more than enough, because if everything collapses, then the value of those gold reserves shoots up, it skyrockets. Secondly, you don't have to fully cover it. That's what experience shows, full coverage is only necessary in a country where there are no other mechanisms to support confidence in the central bank.

DIJKMAN: For example, a country like Canada. I think it has sold all gold. Why did they make that choice?

HOUBEN: Why did Norway put all their oil and gas revenue into a fund and not run it into the government's budget like the Netherlands did? Those are choices that were made politically. I do think that is an important point to make here. This is not a choice that DNB makes alone. This is in consultation with our shareholder. And that is of course the Ministry of Finance, with whom we are in close consultation about our balance sheet and the risks we bear. And also the gold reserves, which are part of that.