Look up the word sustainable in the Oxford English dictionary and you get the following definition: “avoidance of the depletion of natural resources in order to maintain an ecological balance.”

Unfortunately the world’s ecological balance has not been right for a very long time. As a society, we are consuming resources far more quickly than we are replacing them, which is the very definition of unsustainable.

Food production is at the heart of the problem, made worse by climate change, which brings droughts that kill crops and a lack of fresh water for irrigation.

Adding more people puts pressure on finite food resources that can lead to conflicts and in especially stressed regions, hunger.

Since 1950, the world’s population has gone from 2.5 billion people to 7.8 billion. (current world population by Worldometer)

Society demands increased crop yields from agriculture in order to feed growing populations especially in the developing world.

According to the United Nations, the world’s population is expected to reach 9.7 billion by the year 2050 and 10.9 billion by 2100.

It’s estimated that to feed that number of people, global food production will need to increase from 25% to 70%.

The agricultural reforms and resulting production increases fostered by the Green Revolution are responsible for avoiding widespread famine in developing countries and for feeding billions more people since.

Unfortunately though, high-yield growth is tapering off and in some cases declining. This is mostly because of an increase in the price of fertilizers, other chemicals and fossil fuels, but also because the overuse of chemicals has exhausted soils and irrigation has depleted aquifers.

Throw climate change into the mix, and you’re looking at a serious problem.

“Climate change is acting as a brake. We need yields to grow to meet growing demand, but already climate change is slowing those yields,” Lifegate quotes Michael Oppenheimer, a professor at Princeton and co-author of the fifth report by the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change).

Therein lies the quandary. We need higher crop yields to feed more people, but climate change is making that harder to attain. In fact, rising temperatures combined with more intensive agriculture to produce higher yields actually creates a feedback loop, that pushes CO2 levels even higher.

Desertification is human-caused degradation of land, including unsustainable farming, overgrazing, clear-cutting, misuse of water and industrial activities. Climate change accelerates desertification because warmer temperatures dry out once-fertile land, which then makes the area even hotter. Removing plants from the ground also increases greenhouse gas emissions, since they can no longer serve as carbon sinks. As we strip away the amount of available land for food production, we are literally depriving ourselves of the means to survive.

Earth Overshoot Day

One of the few positive outcomes of the coronavirus pandemic, is it has made people realize we are more connected to the Earth, and each other, than we used to think.

According to the Global Footprint Network, an organization that annually calculates the number of days the planet’s biocapacity can provide for humanity’s ecological footprint (the remainder of the year is considered “overshoot”), the essential lesson covid-19 has taught us, is that for all its technological advances, humanity is not immune to the impacts of overusing natural ecosystems, damaging wildlife, and compromising the biosphere. We are not separate from nature — we cannot be healthy on an unhealthy planet. Neither are we separate from one another. We are one biology on one Earth.

The Earth might be big enough for the current 7.8 billion or even the 10 billion as Norman Borlaug, the father of the Green Revolution, discussed below, believed. But the time is quickly coming when our sheer numbers will demand more than the planet can possibly supply.

Some say that number has already been surpassed.

For most of human history we were consuming resources at a rate far lower than what the planet was able to regenerate.

We appear to have crossed a critical threshold. The demand we are now placing on our planet’s resources has begun to outpace the rate at which nature can replenish them.

The gap between this demand and supply is known as ecological overshoot. To better understand the concept think of your bank account — in it you have $5,000 paying monthly interest. Month after month you take the interest plus $100. That $100 is for our purposes your ecological overshoot and its withdrawal is unsustainable.

Overshoot is driven by four factors: how much we consume; how efficiently products are made; the population; and how much nature’s ecosystems are able to produce.

Humans are currently withdrawing more natural resources then our Earth “bank” is able to provide on a sustainable basis. How much more? At today’s rate of withdrawal we need just over another half-Earth. We’re on track to require the resources of two planets by 2050.

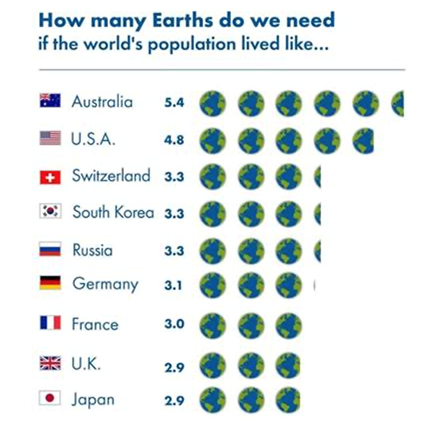

If today, everyone on Earth were to start consuming the same amount of natural resources as the average Australian, we’d need 5.4 planets, an ecological overshoot of 4.4 planets.

According to the Global Footprint Network (GFN) August 22 was Earth Overshoot Day 2020 — the day when humanity exhausted its ecological budget, when our consumption exceeded the environment’s renewable capacity for the entire year.

The rest of the year we were in ecological overshoot. Despite covid-19 lockdowns reducing the global ecological footprint by 10%, we were still using the renewable resources of 1.6 Earths. In 2021 GFN estimates our consumption at 1.7 Earths.

They predict that by 2030, Earth Overshoot Day will be in June – meaning it will take two entire Earths to sustain our species’ consumption.

Green Revolution fizzle

The Green Revolution refers to a series of research, development, and technology transfers that happened between the 1940s and the late 1970s.

Electric motors and irrigation pumps made farming and ranching more efficient. Major innovations in animal husbandry — modern milking parlors, grain elevators, and confined animal feeding operations — were all made possible by electricity.

Advances in fertilizers, herbicides, insecticides, fungicides and antibiotics led to better weed, insect and disease control.

There were major advances in plant and animal breeding — crop hybridization, artificial insemination of livestock, growth hormones and genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

Further down the food chain came innovations in food processing and distribution.

All these new technologies increased global agriculture production with the full effects starting to be felt in the 1960s.

Cereal production more than doubled in developing nations – yields of rice, maize, and wheat increased steadily. Between 1950 and 1984 world grain production increased by over 250% — and the world added a couple billion more people to the dinner table.

The modernization and industrialization of our global agricultural industry led to the single greatest explosion in food production in history. The agricultural reforms and resulting production increases fostered by the Green Revolution are responsible for avoiding widespread famine in developing countries and for feeding billions more people since.

The Green Revolution also helped kickstart the greatest explosion in human population in our history — it took only 40 years for the population to double from 2.5 billion to 5 billion.

We goosed agra machine’s growth and saved a billion people who birthed billions more.

The modern agricultural complex spawned by the Green Revolution may have allowed us to grow more food, but dependence on this high-cost industrial system has come at a high price, mostly for farmers. Following is a summary of Green Revolution failings:

Output did increase, but the energy input to produce a crop increased faster. This is because high-yielding seed varieties only outperform traditional varieties when adequate irrigation, pesticides and fertilizers are used.

The Union of Concerned Scientists notes that monoculture – repeatedly producing the same crop at the exclusion of others — is bad for the soil, preventing the formation of deep root systems and the buildup of organic matter, and hastening the time when the soil can no longer holds its nutrients and irrigation ends up stripping nitrates out of the soil and polluting nearby fresh water supplies.

Monoculture systems — with their lack of genetic variation — are particularly sensitive to bug infestations. Farming methods that depend heavily on chemical fertilizers do not maintain the soil’s natural fertility and because pesticides generate resistant pests, farmers need ever more fertilizers and pesticides to achieve the same results.

The transition from traditional to modern agriculture meant farmers became dependent on industrial inputs. Many have faced severely increased costs because they had to purchase such items as farming machinery, fertilizer, pesticides, irrigation equipment and seeds.

The increased level of mechanization on larger farms removed a large source of employment from the rural economy. New machinery such as gasoline-powered tractors, large self-propelled combines and mechanical cotton pickers, all combined to sharply reduce labor requirements.

Less people were affected by hunger and died from starvation, but many more are affected by malnutrition such as iron or Vitamin A deficiencies. Green Revolution grains do not have the same nutritional values as traditional varieties. The switch from heavily rotated multiple crops to mono-cropping or dual cropping reduces soil fertility and the nutritional value of food.

The rapid increase in farm size and the concentration of production among large producers means 20% of producers generate 80% of the agricultural output.

As a result of modern irrigation practices, aquifers in places like India (once Borlaug’s greatest triumph) and the US Midwest have become depleted. The loss of irrigation water could mean the end of agriculture in these areas.

Green Revolution techniques that rely heavily on chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides, makes today’s agriculture regime much more reliant on petroleum products, making it hard for farmers to reduce their carbon footprints in an era when that is becoming necessary.

In Africa, many farmers have adopted “slash and burn” techniques for clearing farmland for each year’s planting. The cutting and burning process denies the natural return of organic matter and necessitates the use of greater quantities of chemical fertilizers.

In countries like Mali, according to Neverendingfood.org, farmers are finding they are forced to sell off large amounts of their yield to cover the cost of their growing expenditures — depriving families of food and nutritional requirements and lowering their standard of living.

Moreover, to compensate for these losses, more land each year is cleared and planted, leading to the loss of entire ecosystems, and threatening the survival of many indigenous food plants.

Nakedcapitalism.org documented the failure of the Gates Foundation-funded Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, in a recent post titled ‘Why Africa’s Green Revolution Failed’. Author Timothy Wise writes:

According to a new report from a broad-based civil society alliance, based partly on my new background paper, AGRA is “failing on its own terms.” There has been no productivity surge. Many climate-resilient, nutritious crops have been displaced by the expansion in supported crops such as maize. Even where maize production has increased, incomes and food security have scarcely improved for AGRA’s supposed beneficiaries, small-scale farming households. The number of undernourished in AGRA’s 13 focus countries has increased 30% during the organization’s well-funded Green Revolution campaign.

“The results of the study are devastating for AGRA and the prophets of the Green Revolution,” says Jan Urhahn, agricultural expert at the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, which funded the research and on July 10 published “False Promises: The Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA).”

A more recent example of the Green Revolution’s failures comes from India, where farmers have been vigorously protesting the government’s farm reforms. Under the old laws, farmers sold their goods at auction and received a minimum price. The new laws would allow growers to sell their products to anyone for any price. The Modi government says the reforms will increase farmers’ incomes and modernize Indian agriculture, but the farmers disagree, arguing the laws will allow big companies to drive down prices.

Desertification

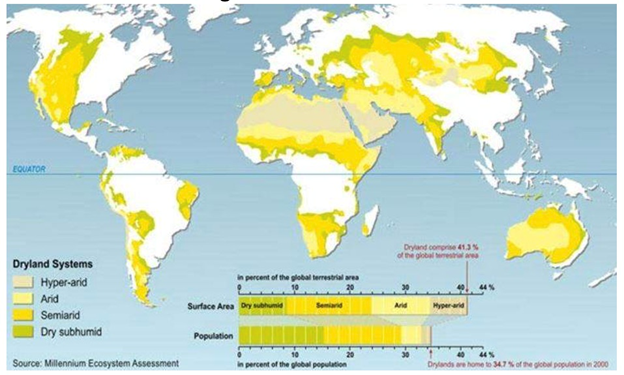

The UN says that by 2030 an area twice the size of South Africa will become unproductive due to desertification, land degradation and drought.

Desertification is a phenomenon that ranks among the greatest environmental challenges of our time.

It’s a process whereby land in arid or semi-dry areas becomes degraded — the soil loses its productivity and the cover vegetation disappears or is degraded to the point where wind and water erosion carry away the topsoil, leaving behind a highly infertile mix of dust and sand.

Desertification is a global issue with more than half of Earth’s arable land affected by soil degradation, according to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification.

Currently 12 million hectares of arable land, enough to grow 20 tonnes of grain, is lost to drought and desertification annually. The issue is said to affect 1.5 billion people in over 100 countries.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization estimates if the phenomenon isn’t stopped, by 2030 Africa will lose two-thirds of its farmland.

The issue of desertification is not new, it has constantly played a significant role in human history, even contributing to the collapse of the world’s earliest known empire, the Akkadians of Mesopotamia.

Climate change

Unfortunately, desertification is made much worse by climate change.

Ranching and farming, through extensive energy inputs like diesel fuel, lights, heating, etc., generate high amounts of carbon dioxide. Farming also releases methane from cows and cow manure, and nitrous oxide from fertilizers. Both are heat-trapping greenhouse gases.

As farmlands expand to meet demand for more food, forests are destroyed to make room for crops. Trees are carbon sinks that trap CO2 and prevent warming. Their removal dampens the forests’ mitigating effects on emissions from farming, therefore temperatures continue to rise, in a feedback loop.

A good example is soybeans. 95% of the soy that is made from soybeans, is used as animal feed. To feed 700 million pigs in China — one for every two citizens — requires the importation of 800 million tonnes of soy. A lot of soybeans come from the Amazon region of Brazil, where rainforests, considered one of the most effective carbon sinks on the planet, must be logged to make room for more soybean farms.

It’s not only the constant clearing of forest for farmland that is a fall-out from climate change. Rising temperatures have also been shown to decrease crop yields.

A 2017 research paper found that each degree Celsius increase would on average reduce global yields of wheat by 6%, rice by 3.2%, maize by 7.4% and soybeans by 3.1%. These foods provide two-thirds of human caloric intake.

A new study showed more than a fifth of global food output growth has been lost to climate change since the 1960s, putting an estimated 34 million people on the brink of famine.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota’s Institute on the Environment found that climate change is already shrinking food supplies, particularly rice and wheat. More importantly in terms of ameliorating global famine, an estimated 795 million people still regularly don’t have enough to eat.

Disturbingly, the study quoted by The Conversation found that rising temperatures have reduced consumable food calories by 1% a year for the top 10 crops – maize (corn), rice, wheat, soybeans, oil palm, sugarcane, barley, rapeseed (canola), cassava and sorghum.

The industrial model dominating American agriculture makes it especially vulnerable to climate changes. Consider cattle ranching, which accounts for a whopping 50% of US agricultural revenue.

Raising cattle for beef consumption reportedly requires 28 times more land, 6X more fertilizer and 11X more water compared to pork, chicken, dairy and eggs.

Not only does industrial-scale beef production use a heck of a lot of resources, it’s also harmful to the environment, emitting about 200 kilograms of CO2 per kg, five times other food sources, and sucking up about 15,000 liters of water per kilo.

Extreme heat and more temperature fluctuations are hard on plants. Heavy rains cause flooding, which can devastate crops and livestock, accelerate soil erosion and pollute water. Droughts are exacerbated by rising temperatures, reduce crop yields and cause irrigation water shortages. Crops near coastal areas can also be ruined by saltwater intrusion as a result of storm surges or rising seas.

Water crisis

Droughts don’t usually come out of nowhere; they are often the result of changing climate and weather patterns.

98% of the world’s water is in the oceans — which makes it unfit for drinking or irrigation. Just 2% of the world’s water is fresh, but the vast majority of our fresh water, 1.6%, is in a frozen state, locked up in the polar ice caps and glaciers. Our available fresh water (.396% of total supply) is found underground in aquifers and wells (0.36%) and the rest of our readily available fresh water is in lakes and rivers.

Put another way, only 0.007% of the Earth’s water is available for drinking, feeding, or fueling (through hydro-electric power or cooling towers needed to run industrial equipment) its 7.5 billion people. We are dancing much closer to the knife edge of water scarcity than we think.

According to the UN, demand for water is expected to grow 55% by 2050, with most of the need (70%) driven by irrigation, to feed the expanding global population, expected to hit 10 billion by 2050. Water for energy use is forecast to rise by 20%.

But the supply won’t be enough to satisfy everyone. By 2025, 1.8 billion people will live in areas where water is scarce, and two-thirds will be residents in water-stressed regions, reports National Geographic.

In North America the major concern is over water levels in the Ogallala aquifer under the US Great Plains — the world’s bread basket. The Ogallala is the world’s largest known aquifer, with an approximate area of 450,000 square kilometers.

It is no longer being recharged by the Rockies and precipitation in the region is only 30-60 cm per year. In three leading grain-producing states — Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas — the underground water table has dropped by more than 30 meters.

Much of the reason for declining groundwater is due to over-use. For example, the Ogallala is being sucked dry at an annual volume equivalent to 18 Colorado Rivers.

A World Bank study indicates that China is over-pumping three river basins in the north: the Hai, the Yellow and the Huai. A 2017 study in ‘Nature Journal’ found that in 10 years, China doubled its use of irreplaceable groundwater from underground reservoirs, and that they are draining faster than they are being replenished.

Globally, the amount of water drawn from aquifers for the purpose of irrigation has increased by a quarter. A third of Earth’s largest groundwater basins are being rapidly depleted says a 2015 study.

The BBC compiled a list of 11 cities with recurring water supply problems. They are: Sao Paulo, Bangalore, Beijing, Cairo, Jakarta, Moscow, Istanbul, Mexico City, London, Miami and Tokyo.

An estimated two-thirds of the world’s population lives in drought conditions for at least one month every year.

A report from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change notes developing countries like India are likely to be worst hit by climate change due to the frequency of droughts, which will lead to water shortages and problems with food production.

The above-mentioned farmer protests in India are partly due to water shortages in the country states a recent Associated Press article. The problem is the government has been subsidizing rice cultivation in northern India but such water-intensive crops have dramatically lowered the water table. The farm reforms do not address the region’s water crisis. AP notes that India is the largest extractor of groundwater in the world, with 90% used for agriculture, in a country that holds just 4% of the planet’s water.

Conclusion

On April 22, US President Joe Biden took the opportunity to host a virtual Earth Day Summit focused on climate action. He pledged to halve US emissions by the end of the decade, stating in opening remarks, “Time is short, but I believe we can do this. We will do this.”

Climate change is an incredibly serious threat that must be tackled in some form over the next decades, but world leaders and their governments mustn’t minimize another elephant in the room, and that is the threat of resource depletion caused by over-consumption, and over-exploiting existing minerals, hydrocarbons, food and water.

When people are hungry, the last thing on their minds is their tailpipe emissions or how their homes are heated/ cooled.

Indeed it would be exceedingly arrogant for developed-nation countries like the United States to lecture the developing world on taking action on climate change, when their populations are struggling to feed themselves.

Just one example: how ethical is it for developing countries to clear land for solar farms when doing so could mean eliminating fields suitable for food production?

It’s also incumbent on world leaders to recognize the many negatives of the Green Revolution and to work with poorer countries to help them achieve food security without driving farmers into poverty, and keeping the land productive by offering alternatives to industrial farming methods that reduce soil fertility and the nutritional value of food.

In short, we need to reduce the impact of human activities on the land we need to cultivate for our very survival.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.