Big problems usually begin as small problems. We see that in nature, where small disturbances become hurricanes, and we see it in the economy, too. So, it shouldn’t surprise us if the economic disturbances of the last years compound into something bigger.

Going into 2020, we already had over a decade of global monetary and fiscal foolishness. QE as a monetary policy tool became widespread worldwide. That was compounded by the insanity of zero interest rate policies (ZIRP) and even negative rates, which massively hurt savers, not to mention pension funds, and caused all sorts of malinvestments.

Among the many ill effects of these policies, one of the most pernicious was to widen the distance between upper- and lower-income groups. Wealth disparity was and is one of the main results of a decade of misguided monetary policy. And now we’re having to pay the price for it, not just in the US but all over the world.

Then we had COVID—both its direct effects on health and the labor force, and additional negative effects from the lockdowns and other countermeasures. Then yet more negative effects as the economies of the world struggled to recover from the disruptions. On top of all that, we have the Russia-Ukraine War and the food/energy crisis it sparked.

In music we have a term “crescendo.” Technically, the crescendo is a gradual increase in volume, which can last a long time. It’s a process, not a single moment. Similarly, the economic volume has been getting steadily louder. The crescendo is approaching its peak, but we have no idea whether that peak will be next year or several years down the road.

This dark symphony was never going to end without sparking a currency crisis, one which allows countries to blame other countries as the source of their own internal problems. We will see that it’s not always the case.

Now, with the US dollar strengthening and others crashing, the crisis is drawing closer.

|

As individual and professional investors are aware, your portfolio could bear the burden if you’re not seeking yield in times like these. Income investing specialist Kelly Green reveals the “Inflation Hideout” that’s helping Americans collect steady 8% yields. |

Currencies are the economy’s backbone. They carry the signals that make everything else possible. Currency values are also moving targets, particularly since they are no longer tied to gold or any other fixed benchmark. The market rules. It decides how many dollars (or euros, yen, etc.) your asset is worth, and it also decides how much each dollar is worth.

Here in the US, we have the luxury of (usually) not having to think about all this. The dollar is the world’s unit of account, giving us the “exorbitant privilege” of settling transactions in our own currency. That’s why we run such huge trade deficits. Our role in the global ecosystem is to import goods and export the dollars that enable global trade.

The US dollar has a critical role around the world that has little connection with the US economy. Vast quantities of dollars are in circulation around the world. Developing countries receive dollars by exporting goods, which they then use to buy imports (often food and energy) from other developing countries. They also borrow US dollars, which they have to pay back from their own currencies being exchanged.

Now follow the bouncing ball. When US imports drop (relative to exports), it means the US exports fewer dollars. The supply of dollars outside our border falls, raising the value of each such dollar vs. other currencies. That’s a problem for the people, businesses, and governments that rely on dollars to pay each other.

When the dollar strengthens in this way, imports to the US are cheaper for Americans. Similarly, our dollars go further when we visit other countries. Nice but it has another side. Foreigners now find it more expensive to buy American exports or visit here. US manufacturers become less competitive against imports. A strong greenback isn’t necessarily great for everyone in the US… but it can be devastating for other countries.

Currency crises occur from time to time. They’re never fun but central banks and fiscal authorities deal with them. But they never address the structural issues that spark these crises.

In Code Red, my 2013 book with Jonathan Tepper, I said this house of cards would end badly at some point. I fear that point is near.

Remember the PIIGS? That was an acronym for the five highly indebted European governments (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, Spain) whose problems threatened the euro currency a decade ago.

After much angst, European leaders kicked the can down the road again. They could do so because the PIIGS economies, while large, weren’t so large as to be unmanageable. Then-European Central Bank President Mario Draghi gave us this famous (infamous?) line:

"Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough."

Last week brought flashbacks to that period when Draghi, who left ECB and then became Italy’s prime minister, lost his job as voters handed the government to a more center-right party (though hardly “the most far right since Mussolini” as scores of newscasts repeated).

But the bigger flashback was in the UK where the Bank of England said it would halt a bond market crash by purchasing government debt at “whatever scale is necessary.”

Whatever it takes, whatever is necessary… Central bankers, accustomed to creating liquidity from thin air, think their words can do miracles. And to be fair, sometimes they can. It worked for Draghi. But the UK is quite a bit bigger than any of the PIIGS were back then.

The UK certainly has challenges. The main one is that it runs a US-like trade deficit but lacks a US-like currency. I know, sterling was once the global reserve. It’s not anymore. This year that problem got worse as the UK lost most of its exports to Russia and had to pay a lot more for imported food and energy.

Not so long ago, the UK was actually exporting energy products, thanks to North Sea oil and gas production. That’s no longer the case thanks to growing domestic demand, along with trade policy and environmental restrictions. The country still has a lot of reserves it could tap if policies changed… which the new Truss government wants to do. That will help but will also take time.

The immediate problem is inflation—considerably worse than we see in the US. Energy prices are a particular sore spot but not the only one. The higher interest rates with which the BOE is fighting inflation also raise housing costs. Many variable-rate mortgages are resetting higher with monthly payments rising sharply. UK homeowners can’t refinance as easily as we can in the US. Food prices are climbing. The peasants are restless, and Parliament is listening.

Last week the new Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng announced a “mini-budget” package with a variety of tax cuts, subsidies, and benefits designed to ease the pain. Some of it has been rather breathlessly compared to Reagan and Thatcher policies. That’s a stretch, but the UK hasn’t seen this sort of thing recently. Actually, rates are just back to where they were in 2012. Not a Thatcher-type cut.

Markets reacted by pushing the pound sharply lower, almost to parity with the dollar. Why? Traders apparently believe the new program will drive government deficits much higher, worsening inflation and pushing interest rates up even more. That, the theory goes, will spark a flight out of the pound before the plan’s tax cuts and other growth provisions can help.

As of Friday, the pound was roughly back where it was before Kwarteng’s announcement that so upset the markets. Turns out that tax cuts weren’t all that much, and the rather large energy subsidies are politically required.

As for the bond market fireworks, it turns out that UK pensions couldn’t meet their long-term obligations at 1% return on British government bonds. Not to worry. London’s clever investment bankers helped pensions leverage up in a rather aggressive way (similar to Long Term Capital Management) but no one considered what would happen if rates were to ever actually rise. As Samuel Rines wrote yesterday:

"The fundamental cause of the UK’s issues are the war / energy prices and the disjointed policy reactions. That is not the FOMC’s problem.”

In fairness, the Bank of England was both raising rates and engaging in quantitative tightening at the same time. I was critical of Bernanke when he did this, when Powell did it, and I still say that you do not conduct a two-variable money policy. Either cut rates or reduce your balance sheet, just not at the same time. It turns out the Bank of England had to reverse its policy in order to keep the country’s pension fund system intact. The circumstances in the UK are different than in the US or Europe, but the principle is the same.

Source: John Mauldin

Unfortunately, the bigger problem is beyond the UK’s control. The US dollar has become what Louis Gave calls a “wrecking ball” to the global economy. Momentum will eventually bring it back in our direction.

One final note on the UK. The long-term policy of Truss’s that would make a huge difference? If the UK actually becomes energy independent and once again an exporter. That is possible, given their reserves. Now that would be an economic game changer and create much-needed high-paying jobs. We will see.

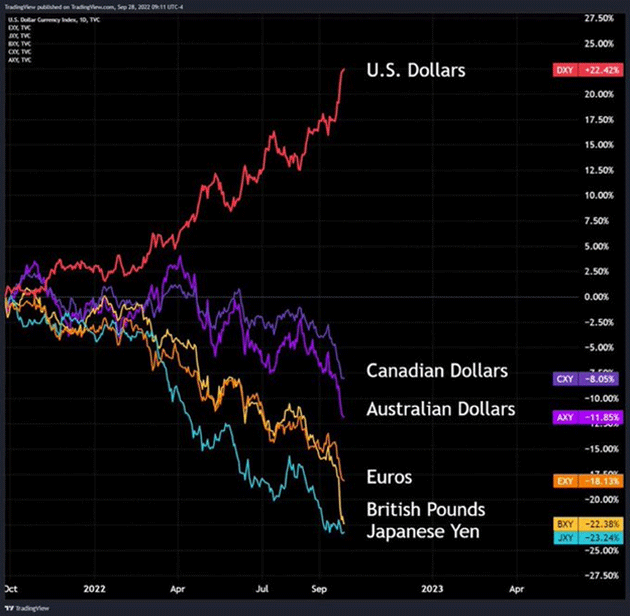

The pound sterling’s meltdown isn’t happening in a vacuum. The Japanese yen also deteriorated in recent weeks for similar reasons, though Japan has its own issues too. The dollar’s sharp rise is affecting everything this year.

Source: TradingView

Worse, this is a problem no one can easily solve. It’s not an unintended consequence of someone’s policy. It’s the post-WW2 global monetary system doing exactly what it evolved to do.

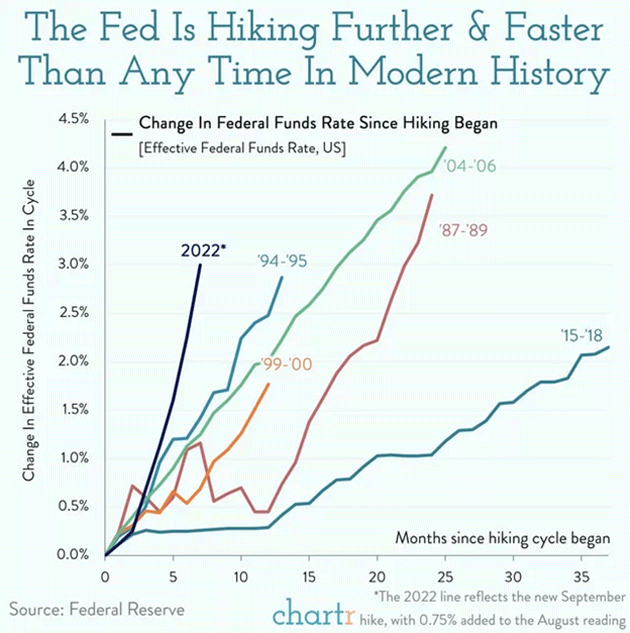

With the Fed on a path to get us to a 5% fed funds rate (my “prediction”), the other central banks need to recognize this. Powell is not responsible for fixing the chaos that passes for monetary policy in Europe. The value of the euro or the pound is not his remit. (As an aside, technically the value of the dollar is the Treasury’s responsibility. Treasury Secretary John Connally quipped to French authorities who complained about Nixon shutting the gold window, “The dollar is our currency, but it’s your problem.”)

Source: chartr

A significant number of people believe the Fed should stop raising rates because the rest of the world is having problems. I strongly disagree. First off, the Fed is not responsible for Europe, Japan, or emerging markets. Its mandates are US price stability and US employment. There has long been speculation about which mandate is more important. At least for the time being, it seems that inflation trumps employment.

Other major central banks have been raising rates too, though less aggressively than the Fed. This partially explains the currency differential. There are multiple reasons for currency rate fluctuation but interest rates are quite important. Complaining the dollar is too strong while holding your own rates below 2% makes little sense.

Just for the record, the BOE’s policy rate is still at 2.25%, the ECB is 0.75%, China is at 3.65%, and Japan is still at negative rates of (minus) -0.1%. Christine Lagarde is telegraphing another 0.75%, which Germany has basically signed off on as inflation is 10% there as it is in much of Europe. Again, just for the record, I recognize that Europe and the United Kingdom have far worse problems with inflation and their economies than the US.

The dollar’s problems will come home, too. They are simply taking time to develop. GMO’s Ben Inker has a fascinating study of currency valuations vs. equity market changes. He goes through a lot of detail but basically, undervalued currencies help local stocks while overvalued currencies hurt. And guess whose currency is most overvalued? Here’s Ben.

“Today’s strong USD looks, in the end, to be our currency and our problem. The USD, alongside the other ‘dollars’ in the developed world, looks to be overvalued enough to be a significant headwind for companies in those countries and it seems likely to weigh on those stock markets over the next few years. The Euro area and Japan look likely to be the biggest beneficiaries, as they are the developed market currencies that are sufficiently undervalued to suggest both strong local earnings and strengthening currencies over the next several years.”

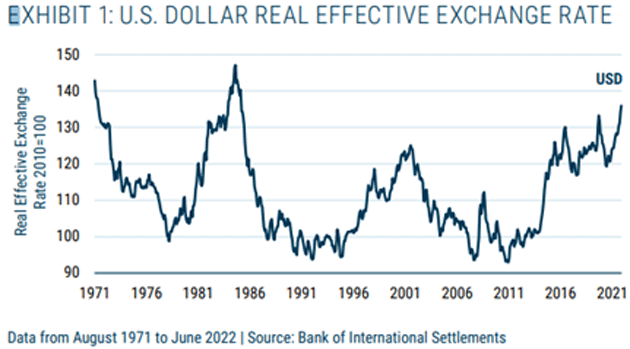

You can see the dollar’s strength here. There is no reason to think that it cannot get stronger for a period of time, but the lesson the chart shows is that currencies fluctuate:

Source: GMO

Ben notes:

“Exactly why the USD has gotten so strong lately is not entirely clear, but one can point to a couple of different drivers. The USD tends to be a safe-haven currency—it rises in tough times for risk assets and falls in boom times. That can help explain the most recent upward jag, but not really the move from 2012‒20 that got us from some of the lowest levels in history to quite elevated. Another recent driver seems to be carry. The Federal Reserve has been more aggressive in raising rates than other developed central banks and currency speculators do like betting on carry.”

“Carry” means that if a Japanese consumer invested in US Treasuries, he would get 3%+ more than he would in yen, and the yen has been in seeming free fall. And soon that carry will rise to 4 and 5%. In short-term Treasuries!

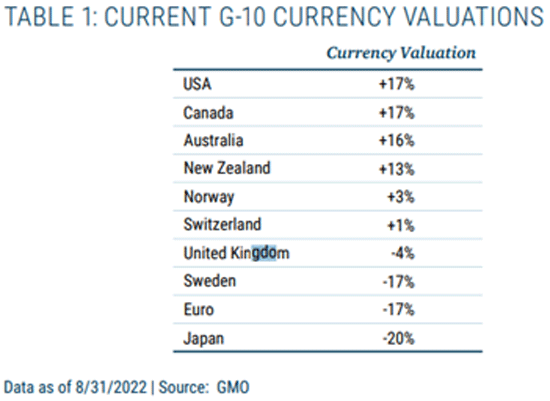

I want to explore Ben’s thought that overvalued currencies are a drag on equity growth. Fist, let’s look at various currency valuations:

Source: GMO

“There are a few countries whose currencies look around as expensive as the USD (oddly, it is every G-10 currency with “dollar” in the name) and at the other end of the spectrum the euro and yen are pretty strikingly cheap. There is good reason to believe these differences should matter, both for the future returns of the currencies themselves and for future equity returns.”

Earnings are the mother’s milk of equity returns. And currency valuations actually feed into earnings, especially at the large global company level. Remember that half of the S&P 500 earnings come from outside the US, with those earnings in weak currencies relative to the dollar. Plus, a strong currency makes our exports, whether equipment or food (wheat, corn, soybeans) more expensive offshore and thus less profitable to US businesses.

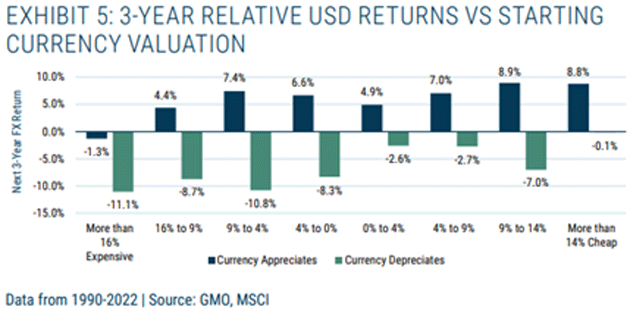

“What this tells us is that equity investors in countries with overvalued currencies have two ways to lose and those with undervalued currencies have two ways to win. On one path, the currency moves back to fair value. If that is true, earnings growth is likely to be about average and the currency move will generate a corresponding equity move on a common currency basis. If the currency does not move back toward fair value, the earnings growth for expensive currency countries will be well below average and growth for cheap currency countries will be far better than average. Countries whose currencies appreciate over the next three years generate better total returns than those whose currencies depreciate, but in either case you’d be much better off in the countries whose currencies were cheap to start with, as we can see in Exhibit 5.”

Source: GMO

I keep saying how past mistakes leave policymakers with no good choices now. That applies pretty much everywhere but especially to the Federal Reserve. Their post-2008 stimuli established the conditions that gave us today’s inflation. Now they must tighten to fight that inflation, but the tightening is driving the dollar up, with all kinds of negative consequences.

Now every choice is bad. The Fed can’t stop tightening too soon or inflation will take over. But if they continue tightening, they’ll generate not just a US recession but a global one, in an economy more leveraged, more fragile, and more interconnected than ever.

This could go many different directions. I doubt we will escape without at least one major sovereign debt default and/or currency devaluation. Europe will have “defaults” but they will be “managed.” Remember Greece? European management meant a lengthy depression for the Greeks.

Compounding the problems created by the ECB, many European countries likely will have to spend giant sums this winter subsidizing energy bills, and perhaps still need rationing and other unpopular measures.

From there, all this crosses outside the bounds of economics. It becomes political, social, and geopolitical. Financially-oriented analysis fails when leaders have to do things that make no financial sense.

In that regard, the mid-November G20 Summit meeting in Bali, Indonesia, could prove very interesting. Exactly who will attend is unclear; some don’t want to be seen with Putin, who himself may not want to leave Russia. Still, it’s possible Biden, Xi, and Putin will all be present, plus many other top leaders: Macron, Scholz, Modi, Kishida, MBS, Erdogan, and Truss could be in the same room.

I, for one, will enjoy seeing Macron and new Italian leader Giorgia Meloni on the same stage, if she is able to form her government by then. They haven’t been on the best terms. But that would be a sideshow to potentially much bigger things. If there’s going to be a new Plaza Accord or something similar, this would be the setting to unveil it.

What they agree on, if anything, may not be the best answer. But it will be the answer we get.

Hurricanes, Denver, Dallas, Birthdays, and More

I thought I experienced a hurricane last week with Fiona. Puerto Rico’s south side certainly did with torrential rains pouring down off the mountains, turning streams into destructive raging rivers and then flooding large areas. But after seeing the pictures of Ian’s toll in Fort Myers and Naples, our experience with Fiona looks more like a very heavy rainstorm, albeit one that took out power, water, etc. Conversations with friends in Naples make it sound rough.

I will be in Denver November 16‒18 and then Dallas before heading to Tulsa for Thanksgiving with the kids and grandkids. I will need to be in Miami soon and Cleveland sometime in October.

I turn 73 next Tuesday, October 4. The last six months haven’t been kind to my body, but I am recovering and getting back into the gym (although the weights are heavier and the treadmill slower). A stretching routine seems to help. My back is too tight to play golf, and I need to fix that.

I’m still far from retirement, starting new businesses and projects just as I always have and enjoying writing the letter. If I retired, I would be doing the same thing I do now, so why not keep doing it and get paid for my “retirement?”

Have a great week and don’t forget to follow me on Twitter.

Your thinking Italy next summer if Europe is still on sale analyst,

|

|

John Mauldin |

P.S. Want even more great analysis from my worldwide network? With Over My Shoulder you'll see some of the exclusive economic research that goes into my letters. Click here to learn more.