The copper price rallied to $10,000 per tonne ($4.53/lb) on Sept. 30 for the first time since July, putting lead in the pencils of copper proponents hoping for another run to the record-high $5.20 per pound reached in May.

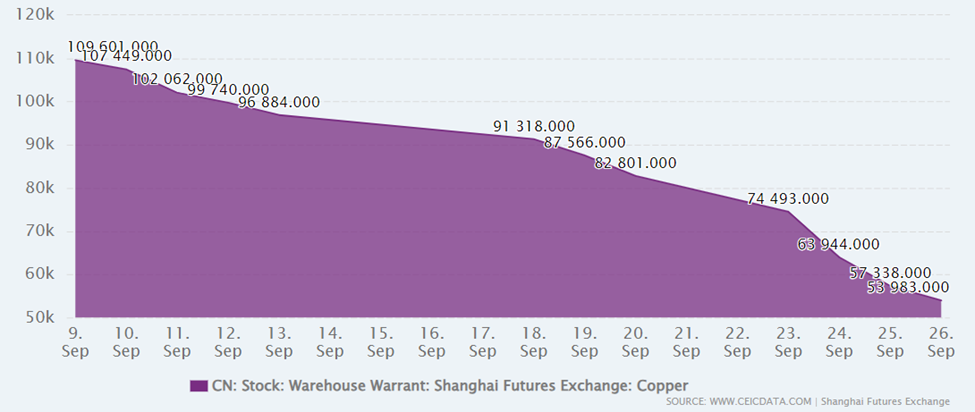

The positive price action was credited to Shanghai copper stocks trending lower in recent weeks, and the fact that China on Sept. 24 announced its biggest economic stimulus since the pandemic.

China Warehouse Stock: Shanghai Future Exchange: Copper stocks were reported at 53,983.000T on 26 Sep 2024. Copper stocks reached an all-time high of 268,889.000 Ton on 13 Jun 2024.

Yahoo Finance reported that in China, the benchmark CSI 300 stock index surged 4.3%, its largest jump since July 2020. Stocks in the United States also rose, but the biggest effect was felt in commodities, with silver rocketing to a decade-plus high, and copper futures notching a 10th straight win as they surged to a two-month high.

Given copper’s necessary usage in the energy transition keeping demand strong, and copper supplies dented by a number of factors including a lack of new mines, lower copper grades, resource nationalism in top copper-producing countries, along with the usual strikes and bad weather that always strip 800,000 to 1 million tonnes of annual supply from the copper market, it looks like the copper bulls are back in charge.

Not so fast.

An updated demand and supply forecast from the International Copper Study Group indicates there is no shortage of copper. The ICSG expects a 469,000-ton global supply surplus this year, followed by a 194,000-ton surplus in 2025. Reuters dutifully reported the scale of oversupply is more than double that forecast when the group met in April.

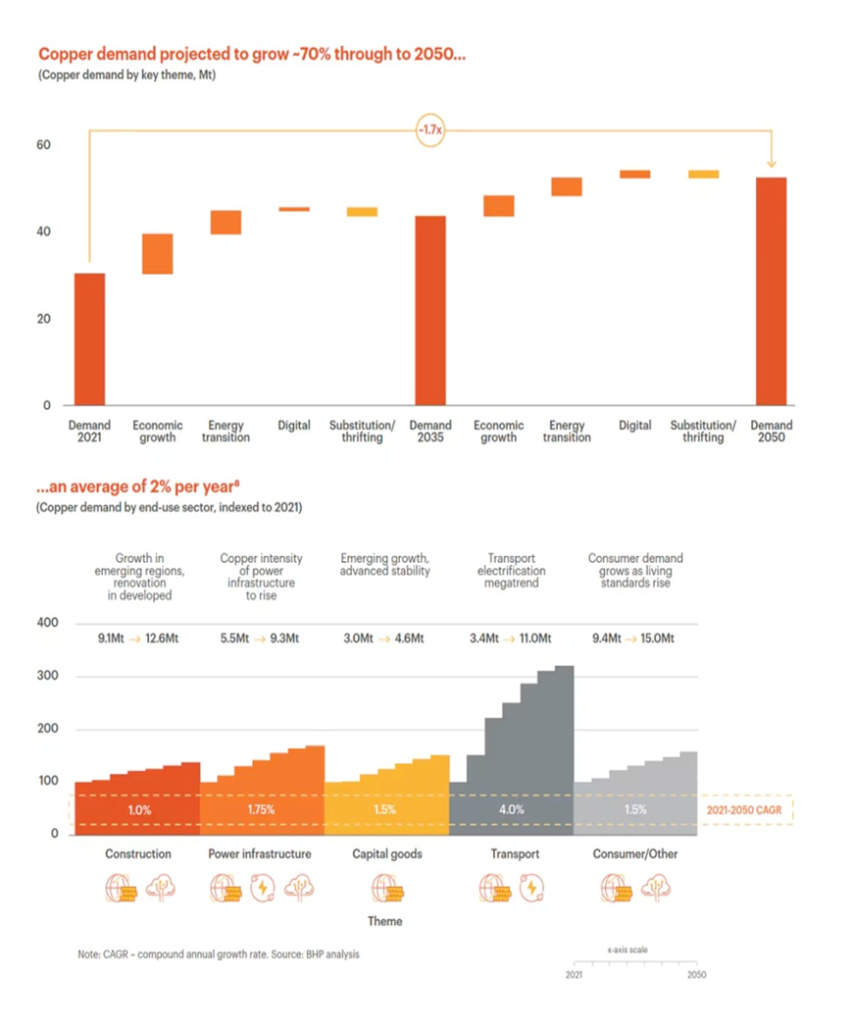

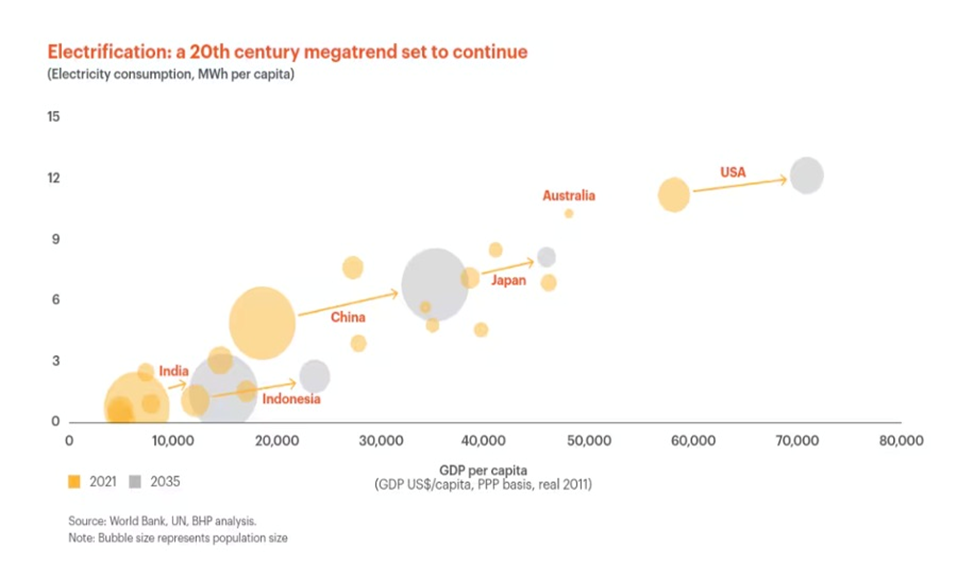

The same day, BHP Group projected that global copper consumption will increase by an additional 1 million tonnes annually (roughly the production of one Escondida, the largest copper mine in the world) until 2035. The increase as suggested above is due to the adoption of copper-intensive technologies like electric vehicles and solar power which require miles and miles of copper wiring. It’s double the growth rate seen over the past 15 years.

The amount of new copper BHP says is required is “off the charts”. We are talking a million tonnes of new copper per year for the next 11 years, or an additional 11Mt of copper by 2035.

BHP says we need to dig up one million additional tons of mined copper next year. The ICSG expects a 194,000-ton surplus in 2025.

Bears

Temporary Poppa bear for our purposes is ICSG.

The group expects mine production to grow 1.7% in 2024 — an upgrade from its +0.5% forecast in April — and for growth to accelerate to 3.5% next year as large mines such as Kamoa-Kakula in the DRC and Oyu Tolgoi in Mongolia ramp up capacity, along with the new Malmyzhskoye mine in Russia entering production.

Refined metal production is expected to grow by 4.2% this year, another upgrade from April, when the ICSG forecast +2.8%.

Copper held in global exchange warehouses touched a four-year high of 599,000 tons at the end of August, and even after a 100,000-to decline in September, they are still 284,000 tons higher than at the start of 2024, writes Reuters metals columnist Andy Home.

Home thinks copper bulls with their rosy demand forecasts should curb their enthusiasm; global demand growth of 2.2% this year will lag refined production growth by a significant margin, hence the expected metal glut, he says.

Mining.com chose a copper-price low point in August to write a copper article. Author Frik Els observed that the bellwether metal was down more than 20% from its mid-May peak, with year-to-date gains all but wiped out.

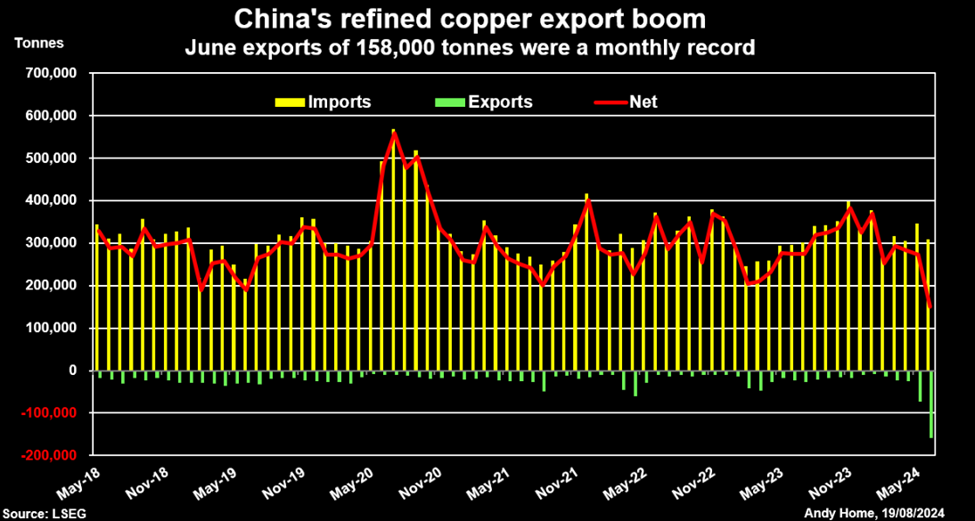

Reuters wrote in an Aug 20th news release, “A rare burst of Chinese exports has deflated bull spirits in the copper market, with funds dumping long positions and prices down by 16% from the record highs seen in May.

The world’s largest buyer of copper shipped out an unprecedented 158,000 metric tons of refined metal in June. First-half exports of 302,000 tons were already higher than any full calendar year since 2019.

Weak Chinese purchasing managers indices show that activity in the country’s manufacturing sector sank to a five-month low in July, reinforcing Doctor Copper’s gloomy message.

Yet demand weakness is only part of the story.

Fast-rising domestic production and a flood of African imports have saturated the local market. And then a ferocious squeeze on the CME (CME.O), opens new tab contract in May opened an equally unusual export arbitrage window for that excess to flow out.”

Els then aimed his cursor at copper prices and called out those who believe in $15,000 a tonne next year and Those who caught copper fever added demand from artificial intelligence data centers and military spending to the often trotted out energy transition.

Fair enough, but before the mining industry finally enters copper nirvana, the next few years are likely going to be brutal.

A new note from Capital Economics reminds industry watchers that copper’s fortunes hang on China.

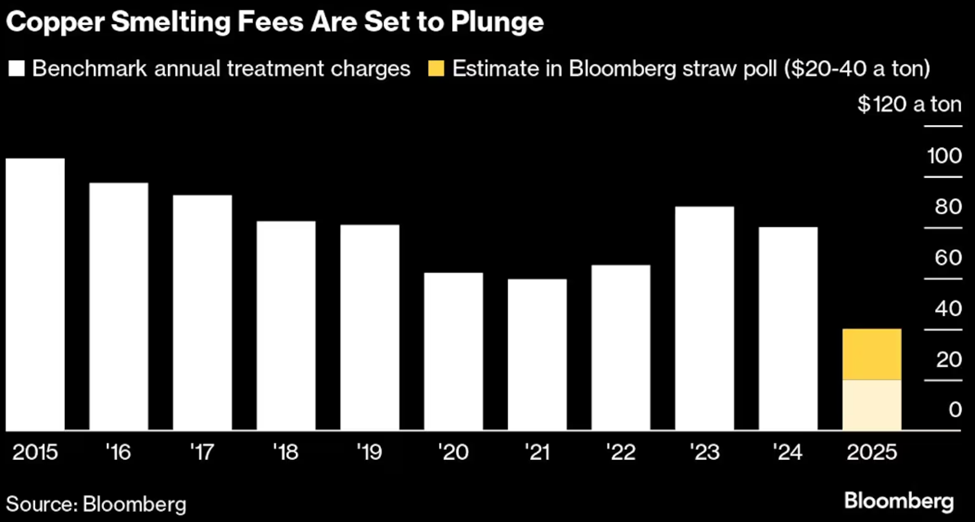

More specifically, the country’s construction sector and its smelters (talk of output cuts was the spark that first lit up the market).

The London-based researcher says rather than a slowdown in the US, the “slow-moving crisis” in the property market in China and ongoing overcapacity will drive copper prices lower.

Output from China’s smelters responsible for more than half global output will remain high and ample exchange inventories will see the country’s copper export prices drop, dragging down prices on global exchanges.

While base metals should get a lift towards the end of the year as China steps up government borrowing and infrastructure spending over the last few months of 2024, by the end of next year copper will be back below today’s levels.

Copper Smelters Warn of Closures as Crunch Talks Get Underway

Bulls

“As we look towards 2050, we foresee global copper demand increasing by 70% to reach 50 million tonnes annually. This will be driven by copper’s role in both current and emerging technologies, as well as the world’s decarbonization goals,” says BHP’s chief commercial officer Rag Udd.

The company expects that by 2050 the energy transition sector will represent 23% of copper demand compared to the current 7%. The digital sector including data centers, 5G and AI is projected to rise from 1% today to 6%.

Transportation’s share of copper demand is expected to climb from about 11% in 2021 to 20% by 2040, thanks to the EV rollout.

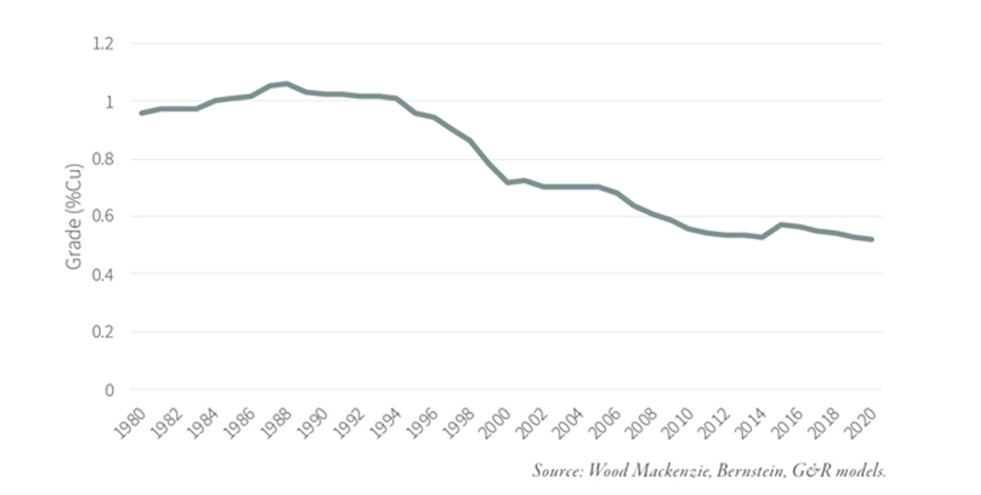

On the supply side, BHP points to the average copper mine grade decreasing by around 40% since 1991. The next decade should see between one-third and one-half of the global copper supply facing grade decline and aging challenges.

The company estimates that an investment of $250 billion will be required to address the widening gap between supply and demand.

Two other sources confirm that huge new investments in the copper sector are required.

According to BloombergNEF’s annual Transition Metals Outlook, the industry will need $2.1 trillion by 2050 to meet the raw materials demand of a net-zero-transmissions world. As stated by Mining.com,

Despite a decade of growth in metals supply, BNEF reports that current raw material availability remains insufficient to meet the rising demand.

The report highlights that critical energy transition metals, including aluminum, copper, and lithium, could face supply deficits this decade —some as early as this year.

The same publication reported this week that capital is the top risk facing the mining sector this year, citing a new report from EY:

“We need about $1 trillion in investment to produce enough metals for the energy transition,” Theo Yameogo, EY Americas and Canada Mining and Metals Leader told The Northern Miner. “We haven’t seen that coming in. Now it’s the #1 (risk) because people are really worried. We’ve seen some M&A, but we haven’t seen direct investment in the mining sector.”

One source points out that senior miners have been allocating a relatively small portion of their revenues to exploration spending, with most expenditures invested in developing existing mines and measures to reduce operating costs.

Metals security of supply depends on junior resource companies — Richard Mills

If the seniors aren’t exploring, and when was the last time you heard of a major mining company making a greenfields discovery, it falls to the juniors. But junior mining financing has dried up; global exploration budgets in 2021 were half of what they were in 2012.

Capital expenditures in mining fell from approximately $260 billion in 2012 to $130 billion in 2020 (corresponding to 15% and 8% of industry revenues, respectively), McKinsey & Company found.

According to Natural Resources Canada, in 2023 exploration spending by juniors declined to $2 billion, down 19% from $2.5 billion in 2022.

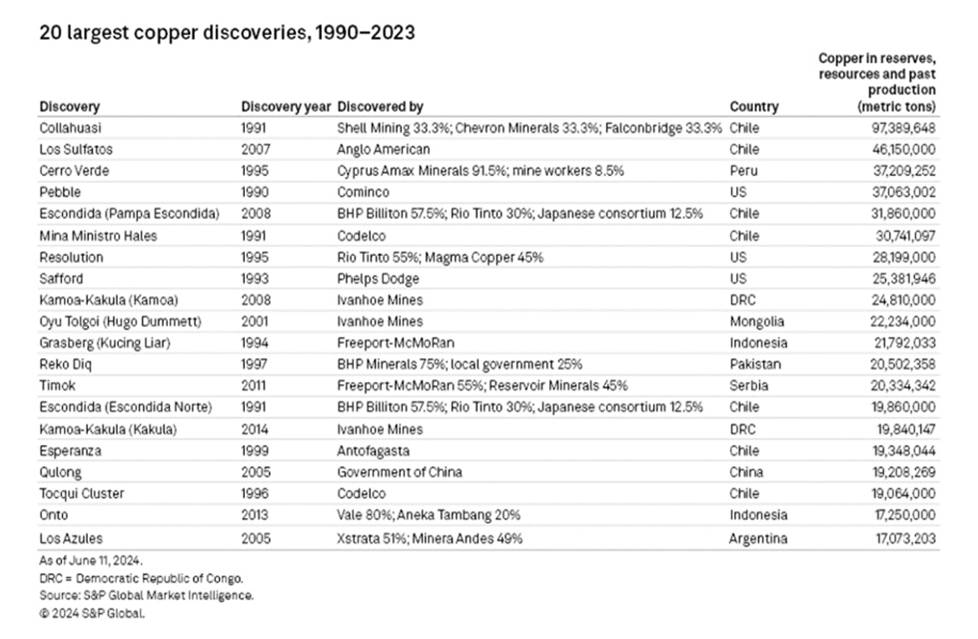

A more recent study from S&P Global finds that major new copper discoveries are getting scarcer, and confirms that older deposits have represented the majority of the reserve growth over the last decade.

Of 239 copper deposits discovered between 1990 and 2023, that met S&P’s threshold of 500,000 tonnes in either reserves, resources or past production, only 14 were from the past decade.

The New York-based analytics firm notes that copper exploration budgets have remained well below levels from a decade ago. While the global exploration budget was 12% higher in 2023, it was 34% lower than the 2012 peak.

“The dearth of recent discoveries is a direct result of the industry’s continued focus on brownfield assets — extending known deposits and assets — rather than the generative exploration that could yield brand-new discoveries,” said Sean DeCoff, author of the S&P report.

According to his analysis, grassroots’ share of the copper exploration budget in the 1990s and early 2000s typically ranged between 50% and 60%. However, in a 2023 survey, early-stage exploration registered just 28% — the lowest on record.

China is the world’s biggest copper consumer, so what happens there is watched closely be copper bulls and bears alike.

As mentioned China in September announced its biggest economic stimulus since the pandemic, which caused big jumps in Chinese and American stock markets, along with commodities.

The aim is to achieve its 5% annual growth target.

Yahoo Finance reported the stimulus — designed to pull the economy out of a slump caused be a property crisis and deflationary measures — includes over $325 billion in monetary measures.

The People’s Bank of China reduced the reserve requirement ratio — the amount required by banks to set aside for loans — by half a percentage point, freeing up about $142 billion in short-term liquidity.

The plan also lowers short- to medium-term interest rates and makes mortgage relief a top priority, says Yahoo Finance.

These moves are expected to benefit about 50 million households, saving them $21.3B annually in interest expenses.

The central bank also introduced a plan to prop up China’s ailing stock market. A $71 billion stock market stabilization program will allow securities firms funds, and insurers to access funding for stock purchases through a swap facility, Yahoo Finance explained.

If China adds fiscal measures (i.e. government spending) to its monetary tools, particularly for infrastructure, Commodities would likely see another big push, impacting everything from US manufacturing to energy sectors.

Copper supply

In 2018 we made a bold prediction: that copper supply is NOT going to be able to keep up with demand, in the long-term. We partly based this on a report from Wall Street commodities investment firm Goehring & Rozencwajg Associates pointing to widespread mine depletion.

G&R found, after studying the various sources of the copper industry’s reserve additions, that very few new discoveries had been made. Between 2001 and 2014, 80% of new reserves came from re-classifying waste rock into mineable ore, i.e., lowering the cut-off grade.

Drawing from a database of 115 mines responsible for four-fifths of total output, the firm discovered the grade of new reserves each year has steadily declined, as a result of this practice.

In 2001, the new reserves grade was 0.80% copper but by 2012, it had fallen to 0.26%. The copper industry was still able to replace all the ore used in production with new reserves, but the quality of those reserves, i.e., the grade, had dropped by nearly two-thirds.

There is only so far a miner can go in lowering the cut-off grade. At a certain point, it doesn’t matter how much the price rises, lowering the cut-off involves too many costs; mining then becomes un-economic.

The authors contend that even with prices above $10,000 per tonne, reserves cannot keep growing, specifically at porphyry deposits, from which 80% of the world’s copper is mined. Their analysis also suggests that “we are quickly approaching the lower limits of cut-off grades,” concluding that

“If this is correct, then we are rapidly approaching the point where reserves cannot be grown at all.” If reserves aren’t increasing, there will eventually be nothing left to mine. Production will have to reach a peak, then decline.

According to BHP, the largest mining company in the world, copper demand in 2023 reached 31 million tonnes, including 25 million tonnes of copper cathode and 6Mt of copper scrap.

According to the US Geological Survey, 22 million tonnes of copper was mined in 2023.

In the US copper production declined. “In 2023, production decreased at a majority of copper mines in the United States, and domestic mined copper output declined by an estimated 11% from that in 2022,” the USGS states.

Now let’s turn to the ICSG surpluses. We can determine how many days of copper supply we have on hand by dividing 469,000 tons — the supposed surplus in 2024 — by 68,493t. Remember this is the amount demanded per day if annual demand is 25Mt. By doing this we come up with 6.8 days; call it a week’s worth of copper supply.

A week of copper supply can easily be eaten up by a strike at a major copper mine, bad weather, protests, etc. Last year’s strike at Las Bambas in Peru meant 47,000 tonnes less production compared to 2022. And that’s just one mine. Every year between 800,000 and a million tonnes of supply never makes it to market for various reasons.

In 2025 ICSG says the copper surplus drops to 196,000 tons. Dividing 196,000t by 68,493t leaves just under three days supply. Hardly enough to plug a hole left by a production loss due to force majeure — when a mine shuts due to events beyond its control.

Now let’s take a peek into the future. BHP forecasts a million additional tonnes of copper are needed per year until 2035 to meet global copper consumption. By the way, it isn’t only BHP using the million-tonne figure.

At the 2022 World Copper Conference in Santiago, Chile, CRU’s Erik Heimlich said that eight projects the size of Escondida are needed over the next eight years. Escondida is the world’s largest copper mine with an annual production capacity of 1.4 million tonnes.

8 Escondidas needed over the next eight years

Next year ICSG is calling for a surplus of 196,000 tonnes, but, according to BHO, admittedly talking their own book, we need an addition million tonnes. If that goal isn’t met, and it’s very unlikely to be, we are looking at an 804,000-tonne deficit.

ICSG points out that it expects mine production to grow 1.7% in 2024 and for growth to accelerate to 3.5% next year as large mines such as Kamoa-Kakula in the DRC and Oyu Tolgoi in Mongolia ramp up capacity, along with the new Malmyzhskoye mine in Russia entering production.

Only 5 new mines, most of the production spoken for.

New copper supply is concentrated in just six mines — Chile’s Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca, Cobre Panama, Malmyzhskoye and the Kamoa-Kakula project in the DRC.

At Cobre Panana, nearly half of the 300,000 tonnes per year (tpy) production goes to Korea. Under a 15-year offtake agreement, Canadian miner First Quantum Minerals will ship 122,000 tpy of copper concentrates per year from Cobre Panama to South Korean copper smelter LS Nikko.

The Kamoa-Kakula copper project is a joint venture between Ivanhoe Mines (39.6%), Zijin Mining Group (39.6%), Crystal River Global Limited (0.8%) and the DRC government. Kakula reached commercial production on May 25, 2021, and while output is currently set for 200,000 tpy in Phase 1, a second phase would add 200,000 tpy and peak production would exceed 800,000 tpy.

In June Ivanhoe signed two offtake deals, one with a subsidiary of its partner firm, China’s Zijin Mining; the other with Chinese commodities trader CITIC Metal, to sell each 50% of the copper production from Kakula — the first of two mines involved in the joint venture. In other words, 100% of Kamoa-Kakula’s Phase 1 production goes to China.

That leaves three mines in Chile — Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca’s “QB2” expansion. In 2016 BHP, the majority owner of Chile’s Escondida, the largest copper mine in the world, committed to spend just under $200 million to expand its Los Colorados concentrator. The expansion would help offset declining ore grades and add incremental copper production to reach an average 1.2 million tonnes a year over the next decade. BHP owns a 57.5% share in Escondida, Rio Tinto owns 30%, and the remaining 12.5% is owned by JECO Corp and JECO2 Ltd.

JECO is a Japanese joint venture between Mitsubishi Nippon Mining & Metals and Mitsubishi Materials Corp. It is not immediately clear whether any of Escondida’s production is bought by JECO Corp.

BHP said in February that the expansion of its Spence mine is expected to be completed within one year. Once the operation hits full production, it would produce 300,000 tpy until at least 2026. Spence ownership is split 50-50 between BHP and Santiago-based Minera Spence SA.

Teck Resources’ Quebrada Blanca Phase 2 project is expected to produce 316,000 tpy of copper equivalent for the first five years of its 28-year mine life. In 2019 the Canadian company closed a $1.2 billion transaction whereby Tokyo-based Sumitomo Metal Mining and Sumitomo Corp will, through an $800 million and a $400 million contribution, acquire a 30% interest in project owner Compañia Minera Teck Quebrada Blanca S.A. (“QBSA”). Like Escondida, it is unclear whether the two Japanese companies will take a portion of QB2’s production, or whether they will simply share in the profits.

One of the mines, Cobra Panama, has been shuttered. The rest are in production or, ramping up production. There is nothing else in the copper production pipeline that can come close, even added together, to add up to one million tons. Indeed, even a prediction of the current surplus dropping from 500t to 200t next year shows the rush of copper to market slowing and the predicament we are in concerning copper supply. Those 5 mines are 80% of our future copper supply and there are no equivalent’s in the pipeline..

Conclusion

The nearly 500,000-tonne forecast by ICSG in 2024 is “the last gasp” of copper surplus brought about by the addition of a handful of large new mines/ mine expansions, including Kamoa, Escondida, Spence and Quebrada Blanca’s “QB2” expansion. ICSG adds Oyu Tolgoi in Mongolia and the new Malmyzhskoye mine in Russia.

A significant percentage of production from these mines is going to non-Western buyers, therefore it shouldn’t be counted as part of global copper supply. For example at Kamoa-Kakula, 100% of initial production will be split between two Chinese companies, one of which owns 39.6% of the joint venture project. Two Japanese companies owns shares in Teck Resources’ Quebrada Blanca Phase 2 project and will likely take a percentage of production. Output from the Malmyzhskoye mine in Russia will almost certainly go to domestic needs, and to Russia’s friends, likely China and North Korea.

How about new mines?

It takes seven to 10 years, at minimum, to move a copper mine from discovery to production. In regulation-happy jurisdictions like Canada and the US, the time frame is more like 20 years.

Copper bears might be in charge of the copper market for the next year, as surpluses are used up. But demand post-2025 is practically certain to outstrip supply, due to continued copper requirements from the energy transition, and continued improvement in the Chinese economy resulting from major government stimulus.

We are one natural disaster, one more Panama resource nationalism episode, one workers strike away from disaster in our global copper market.

Sometime in 2025 surplus is going to turn to deficit.

Of course if we end up getting a recession, all bets are off. If demand craters and production from new mines continues apace, the market could end up oversupplied again, weighing on prices.

Robust consumer spending is more evidence of a raging bull market — Richard Mills

A 1982 ‘everything’ rally will spark multi year bull market — Richard Mills

We at AOTH don’t think that will happen though. All indications point to improving economic conditions amid central bank monetary easing, with lower bond yields and a weaker dollar leading to higher commodity prices, including copper, across the board.

Because reserves at copper mines cannot keep growing by constantly lowering the cut-off grade, because the short-lived rush to market we are experiencing will soon end and that the copper mine cupboard is bare and because of stimulus from China we at AOTH maintain our very bullish take on the copper market.