The US Federal Reserve’s official line is that inflation is only temporary, however we see things differently.

The pandemic has put tremendous pressure on supply chains, and the prices of many agricultural commodities such as grain, corn and soybeans, have skyrocketed. Several industrial metals have enjoyed significant price gains, too, including copper, zinc and lead, as demand for them outstrips supply.

Supply constraints in certain industries plus greater demand for goods and services is a recipe for higher inflation.

Canada’s annual rate of inflation is the highest since 2003, with the consumer price index (CPI) up 4.4% in September compared to a 4.1% year over year increase in August.

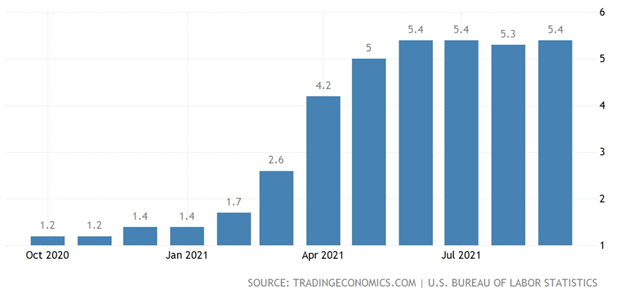

US inflation is even higher at 5.4%. The CPI increased 0.4% in September, with food and rent accounting for more than half of the rise. Food prices reportedly jumped 0.9% last month after increasing 0.4% in August, with the largest rise in food prices since April driven by a surge in the cost of meat.

US inflation rate (CPI)

US inflation rate (CPI)

To the question of whether inflation is temporary, we are seeing increasing evidence it is not, i.e., that rising prices are becoming a persistent facet of the economy. Could this be the 1970s all over again, when inflation hit double digits?

Harvard economics professor Ken Rogoff, writing for Project Syndicate, suggests the parallels between the 2020s and the 1970s just keep growing. Has a sustained period of high inflation just become much more likely? Until recently, I would have said the odds were clearly against it. Now, I am not so sure, especially looking ahead a few years.

Rogoff points to a couple of key similarities between the economic situation 50 years ago and the one currently:

- Supply shocks. In 1973 OPEC cut off the supply of oil, resulting in massive hikes to the international price of crude. Today, protectionism and a retreat from global supply chains are an equally negative supply shock.

- Government spending sprees. President Lyndon Johnson splashed out big-time during his “Great Society” programs of the 1960s, followed by spending to meet the soaring costs of the Vietnam War. The Trump administration was equally magnanimous, doling out around $4 trillion in pandemic relief, as is the Biden administration whose philosophy of “Modern Monetary Theory” has little regard for fiscal deficits.

Another renowned economist, Nouriel Roubini, believes the stagflation threat is real, having warned for months that the current mix of persistently loose monetary, credit, and fiscal policies will excessively stimulate aggregate demand and lead to inflationary overheating. Compounding the problem, medium-term negative supply shocks will reduce potential growth and increase production costs. Combined, these demand and supply dynamics could lead to 1970s-style stagflation (rising inflation amid a recession) and eventually even to a severe debt crisis

Energy inflation

Rogoff’s observation, made at the end of August, that supply shocks are happening both today and in the 1970s, is playing out perfectly with respect to the energy crisis that we see unfolding, particularly in China and Europe.

China was one of the few countries to survive 2020 without falling into a recession. The economy came roaring back in the first quarter with a growth rate of 18.3%, but it has since throttled back to the slowest pace in a year, due to a massive energy crunch, along with shipping disruptions and a deepening property crisis headlined by troubles at Evergrande.

China’s economy expanded by just 4.9% in the third quarter compared with Q3 2020.

According to Forbes, flooding across China’s key coal-producing provinces, resurgent demand for Chinese goods in the wake of pandemic easing, and market distortions including power rationing and price controls, are behind an energy shortage that has pushed coal and natural gas prices to record highs. Emergency power rationing is triggering concerns that households and factories could be left without power just as winter sets in.

Meanwhile in Europe, a colder-than normal last winter depleted natural gas inventories, causing electricity prices to soar, as demand from rebounding economies surged too fast for supplies to match, BNN Bloomberg reported.

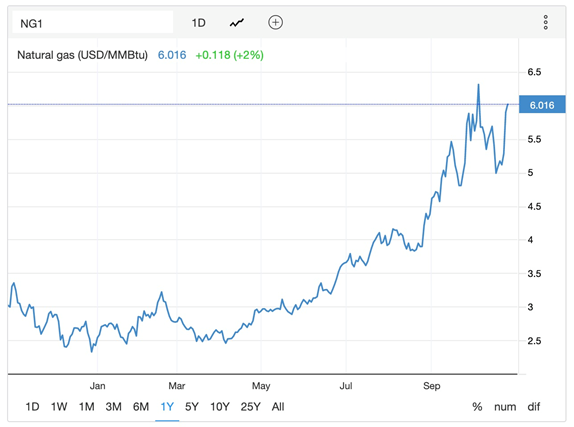

The price of NG is currently six times higher than last year and about four times higher than it was in the spring.

Natural gas futures. Source: Trading Economics

Natural gas futures. Source: Trading Economics

This is nothing new for the European Union which imports 90% of its natural gas, of which Russia is by far the largest source, at 43.4%. The latter is frequently accused of holding back supply to keep prices high, especially this year, reportedly withholding additional gas to force the opening of the newly completed Nord Stream 2 pipeline.

However, the usual energy market dynamics are being overshadowed by the global transition from fossil-fueled energy generation to renewable power sources namely wind, solar and hydro.

As governments and institutional investors divest themselves of funds that traditionally flowed into fossil fuels, i.e. coal/ oil & gas producers, or pipeline infrastructure, they are trying to bring on renewables to replace the lost output.

For example 33-50% of the UK’s electricity came from coal in the mid-2000s; today practically none does. Same with Denmark. About half of Europe’s coal plants are gone or slated to close soon.

However, with no easy way to store the energy generated from renewables, utilities are finding they must continue to utilize “dirty” coal and natural gas, despite commitments to lessen their dependence on fossil fuels to fight climate change.

As Bloomberg puts it, In other words: A strained global gas market triggered Europe’s record-setting spike for electricity prices — and the transition amplified it.

The problem was made worse this year by low output of hydro and wind power sources, due to unexpectedly low wind speeds and little rainfall.

Germany’s ill-fated decision to shutter its nuclear plants, following the 2011 Fukushima disaster, and its failure to store enough natural gas to keep gas plants fed, have amplified the energy crisis in Europe, and kept it dependent on coal.

Earlier this month, electricity prices in Germany reached €300 per megawatt hour, in Spain they hit €288, and in Italy, €308. Those prices are more than 500% above their 2010-20 average, according to a recent Globe and Mail column.

(Germany now has the highest electricity prices in Europe, partly because of past subsidies, Reuters reported. The government this month plans to ease pressure on consumers by cutting the renewable power support surcharge paid to producers — from US$0.065 per kilowatt hour in 2021 to around $0.043 per kWh in 2022. In 2020 the surcharge cost consumers 24 billion euros (US$27.8B). A typical German household saw their power bill rise 9.3% over the past year to a record €1,255 (US$1,457))

Prices for Newcastle coal reached US$280 a tonne, compared to $70-80 six months ago.

EuroNews reports The surge in natural gas prices has driven up inflation across the 19 countries that make up the eurozone as well, according to newly released Eurostat data.

Inflation is at a 13-year high of 3.4% in eurozone countries due to the 17.4% inflation in the energy sector. That was up from -8.2% inflation in the same sector last September.

The problem isn’t about to sort itself out anytime soon, because even though solar and wind power are getting less expensive, many parts of the world still depend on coal and natural gas as a primary source, or as a backup.

The obvious example is the United States. With 40% of the country’s electricity now generated by NG, higher gas prices will inevitably push up electricity and heating bills. US natural gas futures have already more than doubled this year.

Remember the key dilemma: investors are actively dumping coal and oil stocks, and instead are putting funds into cleaner, greener renewables, even though the intermittency factor and the infancy of battery storage technology means we are a long ways from replacing fossil fuels.

Meanwhile power consumption is projected to increase 60% by 2050, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, driven by continued economic and population growth. The ongoing trend towards increased digitization/ 5G, is another major demand source that will need to be satisfied, somehow.

Bloomberg concludes,

The surge in electricity demand combined with fuel-price volatility means the world could be in a for a rocky few decades. The consequences will likely range from periods of energy-driven inflation, exacerbating income inequalities, to the looming threat of power outages and lost economic growth and production.

Food inflation

According to Statistics Canada, food prices are up 2.5% over the past year, but that may be underestimating the impact of inflation. New research from Dalhousie University’s Agri-Food Analytics Lab, quoted by BNN Bloomberg, shows that food inflation in Canada is closer to 5%, well above the normal 1-2%.

Among food categories, meat prices stand out as rising the most, with Stats Canada noting a 10% increase for these products over the past six months. Nearly half of Canadians, 49%, say they have reduced their purchases of Alberta meat.

As for what is causing food prices to tick higher, the study by Agri-Food Analytics Lab cites unfavorable weather patterns in the northern hemisphere, i.e., droughts and storms, and logistical challenges owing to the covid-19 pandemic.

Corporate Knights expounds on the covid factor, mentioning several contributors to higher prices. These include labor shortages in both Canada and the US, rising freight costs, border waits, last year’s temporary closures of meat processing plants, and higher demand for food, as a revival of home cooking puts pressure on the prices of meat and feed grains such as soybeans and corn.

According to BNN Bloomberg, heat-related drops in crop yields affecting the supply of food could be with us for decades:

Yields of staple crops could decline by almost a third by 2050 unless emissions are drastically reduced in the next decade, according to a Chatham House report published [in September], while farmers will need to grow nearly 50 per cent more food to meet rising global demand during the same timeline.

It isn’t only retail food shoppers that are feeling the pinch of rising prices. Inflation is just as much a factor at the bottom of the food supply chain, the world of farmers and ranchers, as at the top, the shelves of brand-name grocery stores where most of us peruse items for our weekly shop.

One of the most important inputs that farmers rely on for growing food is fertilizer. Higher fertilizer prices must often be passed onto the end user, the buyer of fruits and vegetables, for the grower to preserve his profit margin. This is precisely what we see happening right now.

Recently the Green Markets North American Fertilizer Index hit a record high, rising 7.9% to US$996.32 per ton, and blasting past its 2008 peak. According to BNN Bloomberg, the fertilizer market has been smoked this year due to extreme weather, plant shutdowns and rising energy costs — in particular natural gas, the main feedstock for nitrogen fertilizer.

Green Markets says expensive fertilizer could push US corn farmers’ cost of production costs 16% higher.

Climate change & supply

The pandemic has certainly been influential in food price increases, but it would be a mistake to think that inflation will subside once the pandemic is over.

One of the most important factors driving food inflation is climate change. Global warming is obviously not a temporary phenomenon.

In 2018 the world’s leading climate scientists warned there are only 12 years to go for warming to be kept to a maximum 1.5 degrees C. If, after a dozen years, not enough is done to slow global warming, a tipping point will be reached, beyond which the risk of droughts, floods and extreme heat, will significantly worsen.

Scientists say that record heat waves lasting longer than a week, such as the “heat dome” that enveloped residents of western Canada and the United States this past summer, will be two to seven times more likely — creating the conditions that spark wildfires, cause droughts/ water shortages, and increase the frequency of extreme weather events that often ravage farmland and disrupt supply chains around the world, forcing food prices to rise year after year.

Is drought-caused food inflation transitory? I don’t think so.

Wage inflation

In a normal growing economy, wage growth is a happy consequence of increased aggregate demand.

However this economy is anything but normal, with Practically the entire post-pandemic agenda built around policies that stoke demand and discourage work, making supply-side constraints entirely predictable, writes John Cochrane, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, in a recent Project Syndicate article.

Titled ‘The Revenge of Supply’, Cochrane maintains that we should not accept the Fed’s excuse that “supply shocks are transient symptoms of pent-up demand.” Rather, we should ask, “Why is the supply capacity of the US economy so low?”

The answer is at once disarming and obvious: it’s because of all those “stimmy” checks sent to millions of Americans during the depths of the pandemic. Cochrane observes that, although there are 10 million job openings, 3 million more than before the pandemic, only 6 million people are looking for work. This overabundance of jobs versus job-seekers should inevitably drive wages higher to get those job openings filled.

But the difference between this and previous economic recoveries, at least in the US, is that the government gravy train is still running. And at the risk of mixing metaphors, when the government trough is full, there will be no shortage of swine. Cochrane writes:

We know two things about human behavior: First, if people have more money, they work less. Lottery winners tend to quit their jobs. Second, if the rewards of working are greater, people work more. Our current policies offer a double whammy: more money, but much of it will be taken away if one works. Last summer, it became clear to everyone that people receiving more benefits while unemployed than they would earn from working would not return to the labor market. That problem remains with us and is getting worse.

I couldn’t agree more. The same thing is happening in Canada, with thousands of low-paid workers preferring to sit at home while getting the CERB, rather than show up to a lousy job that comes with the risk of catching covid or getting into an argument with an anti-vaxxer.

Cochrane also points out that the inflation which has followed the Biden administration’s attempt to spend its way out of the covid-caused recession, easily refutes adherents of Modern Monetary Theory like the Democratic Party’s left wing and presumably President Biden himself:

Equally, one hopes that we will hear no more from Modern Monetary Theory, whose proponents advocate that the government print money and send it to people. They proclaimed that inflation would not follow, because, as Stephanie Kelton puts it in The Deficit Myth, “there is always slack” in our economy. It is hard to ask for a clearer test.

And a clearer answer!

Monetary & fiscal policy

Struggling to contain the economic fallout from the pandemic, central bankers have realized that keeping interest rates low and maintaining monthly asset purchases (i.e. quantitative easing), have not given the desired economic boost; now they are counting on fiscal policy, i.e., government spending and taxes, to do the trick. However, the US government does not have the money, so they borrow (print) it, at current rock-bottom interest rates.

The US budget deficit totaled $2.7 trillion for 2021, not as high as 2020’s $3.1 trillion but almost triple 2019’s $984 billion, and that is before President Biden’s $1.9 trillion covid-19 relief package voted into law earlier this year.

More spending is on the way. A LOT MORE. Legislation passed by the Senate but not yet the House of Representatives includes the $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill and the $1.75 trillion “reconciliation” bill (scaled back from the original $3.5T White House proposal which was scaled back from progressive Democrats original $6.5T). The latter is for the most part a wish list of Democratic priorities. It includes three main health care programs — Medicare, Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act; an expanded child tax credit to 2023; and a shortened version of paid family leave from 12 weeks to four weeks.

Though some of this spending is to be offset by tax increases, we don’t believe for a minute that a good proportion of it will not be borrowed, printed, or both.

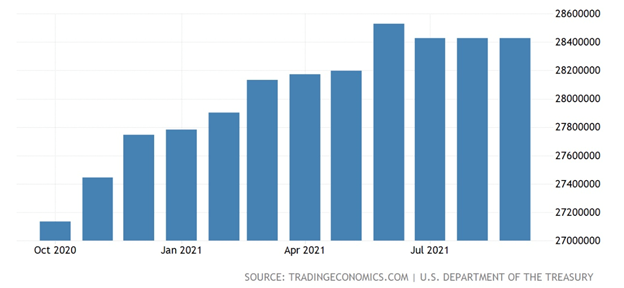

Remember, the US government has already spent $4.5 trillion on pandemic-related relief, helping to boost the national debt to $28 trillion in under a year.

The now-almost $29 trillion national debt doesn’t include what the Biden administration has already spent on pandemic relief ($1.9T). It doesn’t include the now $1.75T spending bills being debated by Congress, and it also excludes the $3T deficit on Biden’s proposed $6 trillion budget.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is projecting that with all of this year’s spending, the national debt in 2021 could balloon to $35 trillion!

US national debt

US national debt

A recent blog post from the libertarian Foundation for Economic Education makes clear it is not military spending nor tax cuts that are driving the unheard-of shortfalls, but the various entitlement programs needed to keep Social Security and Medicare from collapsing.

It calculates the annual interest payments on the debt that taxpayers must finance are set to reach $1 trillion, meaning even with a modest interest rate hike, that sum could skyrocket. Currently taxpayers must spend $800 million a day on debt servicing costs. Going further down this path would mean higher taxation, along with slower economic growth and lower paychecks, “as the debt crowds out private sector investment and drags down the economy.”

Conclusion

There is a historically close correlation between gold prices and debt to GDP. The higher the ratio, the better it is for gold.

As deficits grow and interest rates eventually rise, the CBO predicts the debt to GDP ratio could reach 202%, from the current 125%. At that rate, for every dollar the US economy produces, $2 is borrowed.

Remember, we have monetary easing happening at the same time as fiscal spending “carte blanche”, courtesy of Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT.

Meanwhile the fear of inflation continues to keep gold prices buoyant, with gold seen as an inflation hedge.

Inflation erodes the purchasing power of fiat currencies and eventually they become worthless.

The dollar has lost 90% of its purchasing power since 1950.

By contrast, since 1972 gold has gone from $35/oz to $1,800.

The prevailing trend is to blame inflation on the pandemic, and it does bear some responsibility. Labor shortages in Canada and the US, rising freight costs, border waits, last year’s temporary closures of meat processing plants, to name a few factors, have resulted in higher than normal food inflation.

We now have energy inflation, because of too massive a shift to renewables and a de-investment in fossil fuels, before renewable energy is ready to take the place of oil, natural gas and coal. The result has been electricity prices 500% higher than normal in Europe, and in China, record-high prices of coal and NG, thus squeezing economic growth in the world’s biggest commodities consumer.

An overabundance of jobs versus jobseekers in the United States is fueling wage inflation. The US economy faces a shortage of workers, driving wages and salaries higher. A lack of affordable child-care and fears of contracting the coronavirus are still keeping many female workers at home. Republicans blame the Biden administration’s enhanced unemployment benefits, including a $300 weekly check, for providing a disincentive for returning to work. The same thing is happening in Canada with the overly generous CERB/ EI benefits.

But covid-19 only tells part of the story of inflation, which at its current 5.4% level, is ringing alarm bells, or should be.

A large increase in the money supply is another factor.

Consider: “quantifornication” is still going on in the US, Britain and the EU, meaning that excessive money-printing is continuing to devalue currencies at an alarming rate (this, by definition, is inflation, because it takes more units of currency to buy the same amount of goods as before).

Trillions more in economic recovery spending is promised, with little concern over the mounting debt pile.

Central banks are having to walk a tight rope between keeping rates low enough to keep economic growth going after more than a year of virus-caused economic pain, and stopping inflation from getting out of hand.

Pandemic-related supply constraints might be temporary, and money-printing and currency devaluation could be transitory, although all of the above are likely to be with us for some time.

Structural supply deficits, climate change, drought-caused food inflation, an energy crisis caused by over-exuberant investing in renewables at the expense of fossil fuels, are not temporary. Neither is Modern Monetary Theory, as long as the Democrats are in charge.

The inescapable conclusion? Inflation compounds year after year and the purchasing-power loss your currency experiences will never be regained.

Inflation is going to continue — you better be prepared for scarcity, insecurity of supply, and much higher prices.

We know holding gold or silver is our best insurance.

Richard (Rick) Millsaheadoftheherd.com