For more than three decades, the price of money has been falling. Since March of 2022, when the US Federal Reserve orchestrated a series of consecutive interest rate increases, it has been going up.

It’s hard for the average person to conceptualize the price of money. The idea appears abstract. In fact it is simply the rate of interest. The prevailing interest rate reflects the supply and demand for money. When people save more, interest rates go down because less money is demanded. When they save less, borrow and spend more, the demand for money across the economy increases, and interest rates rise.

Central banks largely determine the price of money by controlling interest rates. But it’s a careful balance. The rate needs to be close to the “natural rate of interest”, which is the price of money that balances saving and investment while keeping inflation stable — in the US and Canada the inflation target is typically 2%.

Set the interest rate below the natural rate, and money becomes too cheap. There is too much investment in the economy, not enough savings, and the economy overheats, leading to inflation.

The alternative is equally bad when the interest rate exceeds the natural rate of interest. This may result in too much savings, not enough investment, and a rise in unemployment.

For over 30 years, borrowing costs in the US have been falling. Adjusting for inflation, the natural rate of interest for 10-year government bonds went from a little more than 5% in 1980 to under 2% over the past decade. (Bloomberg, Nov. 5, 2023)

The fall in the price of money had profound consequences for the economy. Record-low borrowing costs meant households took on bigger mortgages, setting the stage for the sub-prime mortgage debacle of 2007 and the 2008-09 financial crisis.

There is ample evidence to suggest this trend is changing. Recently the yield on the 10-year Treasury note hit 5%, the highest in 15 years.

While the Fed announced at its Nov. 1 meeting that it will hold interest rates steady at 5.5%, the central bank has raised rates 11 times since March of 2022 in an effort to control decades-high inflation.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell said the situation “remains something of a riddle”, with policymakers struggling to determine whether financial conditions are already tight enough to control inflation, currently at 3.7%, or whether the surprisingly-hot US economy needs further restraint.

Following are five reasons the cost of money will remain high, in the US, for the foreseeable future.

Strong growth

To forecast where the future natural rate of interest might go in, Bloomberg built a model of the biggest factors driving the supply of saving and demand for investment. The data set, which analyzed 12 advanced economies over 50 years, found one of the most important reasons for the drop in the natural rate was weaker growth.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, more workers plus productivity gains pushed average annual GDP to nearly 4%. “Strong growth created a power incentive to invest — lifting the price of money,” states Bloomberg.

“By the 2000s those drivers were running out of steam. After the global financial crisis of 2007-08, average annual GDP growth slumped to around 2%. A more sluggish economy meant the attractiveness of investing for the future was weaker — dragging the price of money lower.”

Canada is an example of a slow-growing economy whose central bank is probably done raising interest rates. Indeed, the attractiveness of investing in the Canadian economy is currently weak. On Oct. 31 the Globe and Mail reported the economy has stalled as higher interest rates weigh on growth. GDP is on track to fall by 0.1% in the third quarter, after a 0.2% drop in the second quarter. Two consecutive quarters of declining GDP put Canada in a “technical recession.”

The Bank of Canada’s tightening cycle appears to be working; annual inflation has fallen to 3.8% from a peak of 8.1% last summer. The central bank projects a return to 2% inflation by mid-2025.

“This is yet one more crystal clear sign that the Bank of Canada should be done hiking,” Benjamin Reitzes, a Bank of Montreal strategist, wrote in a client note, via The Globe.

The situation is much different in the United States, where annualized growth of 4.9% in the third quarter was the quickest expansion since the final quarter of 2021.

Why the discrepancy? A recent column suggests “interest rates are biting more in Canada, because of higher household debt loads and mortgages that roll over more quickly. Meanwhile, the U.S. government is running proportionally much larger deficits and pumping more money into the economy. And U.S. productivity is soaring even as it slumps in Canada, adding to American outperformance.”

What does that mean for the price of money? The column by Mark Rendell and Jason Kirby says the strength of the US economy increases the odds of another Fed rate hike. This fits with the above maxim, that strong growth creates a powerful incentive to invest. The column notes that US businesses are investing in buildings and equipment, building up inventories and bringing on new workers, while Canadian companies are pulling back and bracing for a period of slow growth.

The relative weakness of the Canadian economy suggests that the Bank of Canada will move first to lower interest rates, said Avery Shenfeld, chief economist at Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce. Another way of saying this, is that the cost of money in the United States will remain higher for longer.

Changing demographics

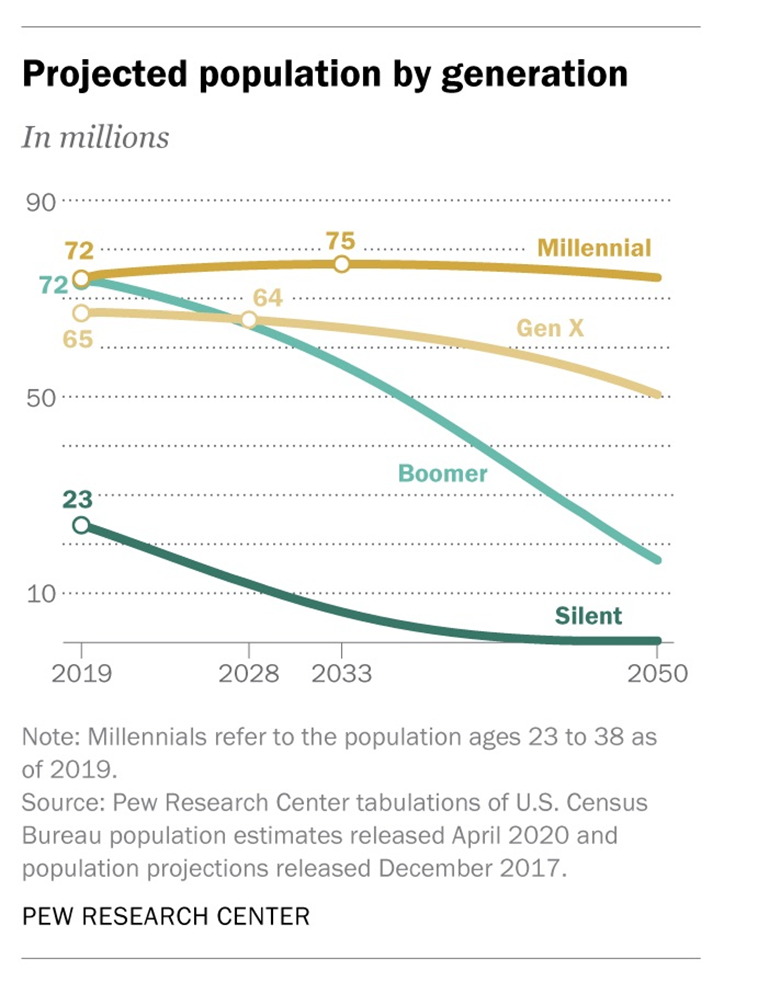

In 2019, Millennials surpassed Baby Boomers as the nation’s largest adult generation, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, via Pew Research.

Millennials numbered 72.1 million that year, compared to Boomers who were only 71.6 million. The Generation X cohort, which totaled 65.2 million in 2019, are expected to overtake the Baby Boomers in 2028.

Lower savings

The reason this is important for the economy is that as a generation, Baby Boomers are prolific savers. From the 1980s on, as the Boomers started saving for their retirement, the country’s supply of savings went up, which put downward pressure on the natural rate of interest.

Now that the generation that helped push borrowing costs down is exiting the workforce, the savings supply is falling. That’s because the generations that followed them — Gen X and the Millennials — have not managed to sock away money for retirement to the same extent.

Most Gen Xers, born between 1965 and 1980, are failing to meet retirement savings targets, with the typical Gen X household squireling away just $40,000, according to the National Institute on Retirement Security.

The cards also seem to be stacked against Millennials when it comes to saving for retirement, between inflation now being at its highest rate in nearly 40 years, the cost of owning a home becoming increasingly expensive, and student loan debt.

In a 2021 Millennials Readiness for Retirement study, via CNBC, Millennials had a lower net wealth-to-income ratio between the ages of 28 and 38 compared to that of previous generations.

The current period of economic uncertainty is piling more pressure on working-age adults to find money in their budgets for savings.

According to recent data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the personal savings rate— how much people save as a percentage of their disposable income — in August was 3.9%, well below the 10-year average of 8.9%. Cash built up from stimulus funds doled out during the covid-19 pandemic are now mostly gone, and soaring inflation in the wake of the pandemic has made it harder to make ends meet.

China

For decades, China’s thirst for practically every commodity under the sun meant a fast-growing economy. In 2010 the country was let into the World Trade Organization, ushering in the era of globalization. Many American jobs were outsourced to China and the US trade deficit with China grew, as Chinese imports outstripped US exports. Complaints of intellectual property theft and one-sided lack of access to the Chinese market by American firms culminated in the US-China trade war started by then-President Donald Trump.

With Biden now in charge, most of the tariffs on Chinese and American goods remain. Moreover, relations have deteriorated not only on trade matters, but geopolitics, with near-constant tensions in the South China Sea between the US and Chinese navies. Taiwan is a related irritant, with the United States claiming the island as an ally, and Beijing wanting to reunite what it considers a renegade province with the Motherland.

It was recently reported that last fall, China passed a milestone. According to The Wall Street Journal,

For the first time since its economic opening more than four decades ago, it traded more with developing countries than the U.S., Europe and Japan combined. It was one of the clearest signs yet that China and the West are going in different directions as tensions increase over trade, technology, security and other thorny issues.

How does all of this affect the price of money? One of the main consequences is a slowing of the flow of Chinese savings across the Pacific into US Treasuries.

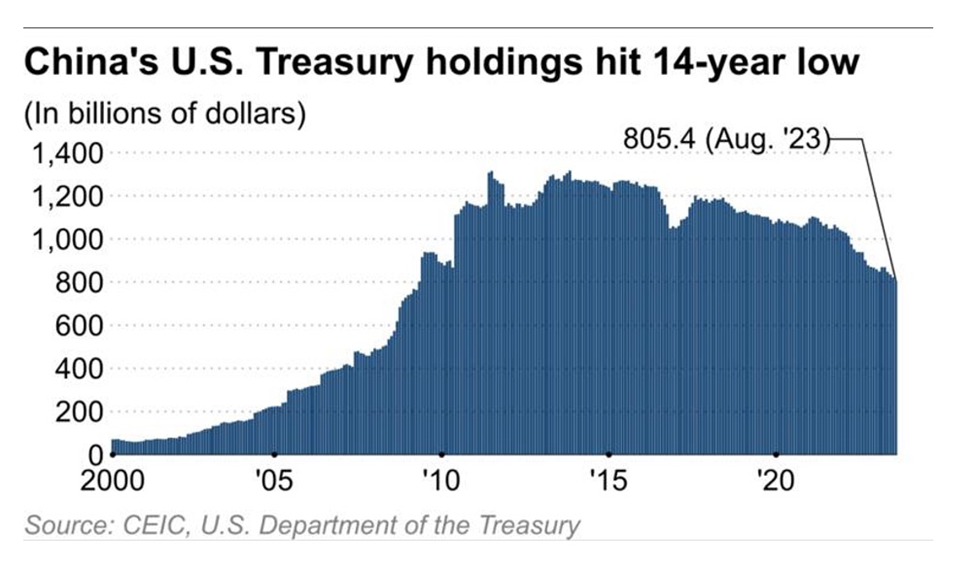

This week, Nikkei Asia reported that the country’s stockpile of US government debt hit the lowest level in 14 years at the end of August — $805.4 billion, down 40% from a decade earlier.

The publication reminds us that China once actively bought the securities with its ample foreign exchange reserves, becoming the second-biggest foreign investor in US Treasuries after Japan.

Given the size of China’s holdings, if Beijing continues to sell Treasuries it could roil US bond prices, pushing up interest rates, or in today’s article’s parlance, hike the price of money.

High government borrowing

High government borrowing

Because the cost of servicing the debt has been so low, the government could continue to spend on big-ticket items like education, health, infrastructure and the military.

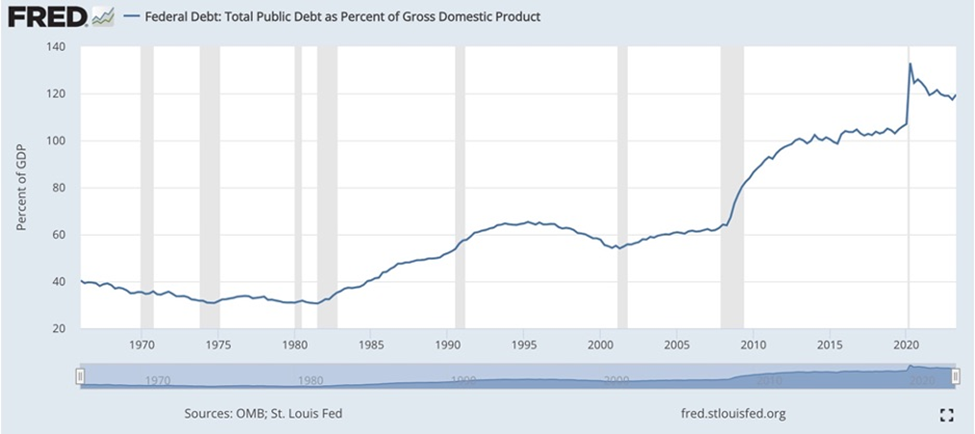

Rock-bottom interest rates over the past several decades, not counting the last two years when rates have been rising, meant that the US federal debt has more than tripled, from 33% of GDP at the turn of the century to 119% today.

This severely limits how much the Fed can raise interest rates, due to the amount of interest that the federal government is forced to pay on its debt.

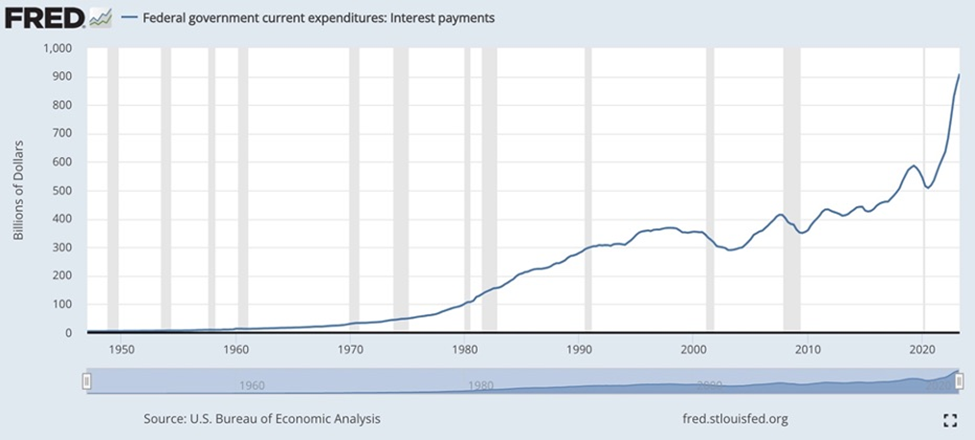

During 2021, before interest rates began rising, the federal government paid $392 billion in interest on $21.7 trillion of average debt outstanding, @ an average interest rate of 1.8%. We calculated if the Fed raised the federal funds rate (FFR) to 4.6%, interest costs would hit $1.028 trillion — more than 2021’s entire military budget of $801 billion!

Interest on the debt to track to exceed military expenditures

We’ve already blown past that. The FFR is 5.5%, compared to 3.5% a year ago.

Each interest rate rise means the federal government must spend more on interest. That increase is reflected in the annual budget deficit, which keeps getting added to the national debt, now sitting at a shocking $33.6 trillion.

Source: FRED

Source: FRED

Source: FRED

Source: FRED

Indeed, rising debt is creating upward pressure on long-term borrowing costs. How much higher could the natural rate of interest go?

Bloomberg’s model shows about a 1% rise by 2050, meaning 10-year Treasury yields could settle at between 4.5 and 5%.

However, if the government doesn’t get its financial house in order, fiscal deficits will continue to widen. Unfortunately, the risks are skewed towards higher borrowing costs, states Bloomberg, noting for example that achieving net-carbon emissions will cost an estimated $30 trillion.

The publication says the combined impact of high government borrowing, more spending to fight climate change, and faster growth will all drive the natural rate higher. A natural rate of 4% translates to a nominal 10-year bond yield of about 6%.

Conclusion

The shift from a falling natural rate of interest to a rising natural rate has major consequences for the US economy. One example is the price of housing. Low interest rates since the 1980s made US house prices soar, and put many new homeowners into the market. Now that mortgage rates are higher, this trend could stop. So far the results are mixed. US News reported in October that while home prices are falling in many parts of the country, in other regions they are climbing.

The Canadian Real Estate Association reported that Canada’s housing market continued to cool last month, with the number of homes sold falling for three months in a row and benchmark prices slipping.

Higher interest rates, of course, have a similar dampening effect on equity markets. Bloomberg notes that since the early 1980s, the S&P 500 has powered higher in part due to low rates, but with borrowing costs on the rise, the impetus for increasing equity valuations will be taken away. So far it hasn’t happened. Despite market turbulence, the S&P 500 has gained 14.6% over the past year, the Dow Jones is up 3.8%, and the Nasdaq Composite roared 27.9% higher.

Unsurprisingly, given what has been written about Canada, the S&P/TSX Composite Index has barely stayed in the green over the past year, moving up by only 1%.

Bloomberg concludes the biggest loser from higher rates will be the US Treasury Department, which will have to pay a lot more interest on the debt, while the biggest winners will be savers and bondholders:

Even if debt rose no further relative to the size of the economy, higher borrowing costs are set to add 2% of GDP to debt payments annually by 2030. If that had been the case last year, the Treasury would have paid out an extra $550 billion to bondholders, which is more than 10 times the amount of security assistance the US has funneled to Ukraine so far.